French or English? The burning question of language in the Maghreb

In their attempt to address the challenges facing Maghreb societies, intellectuals, university professors, artists and politicians find themselves grappling with the burning question of language.

It is often argued that economic and scientific development in the Maghreb would benefit from a shift from French to English; the underlying assumption being that the French language limits access to the modern world of technology and science. Once freed of the shackles of la Francophonie, goes the argument, the Maghreb peoples would see the light.

Once freed of the shackles of la Francophonie, goes the argument, and the Maghreb peoples would see the light

Of course, nothing bears out the assumption that ditching French for English would remedy the economic, scientific and cultural underdevelopment of Maghreb societies.

This is merely a continuation of the kind of misleading thinking which obfuscates the origins of failure - the state's flagrant mismanagement of education, the economy, politics and culture.

The subaltern/master relationship inherited from colonisation means that the learning of a foreign language, French in the Maghreb context, is the way to individual self-realisation; it entitles its speaker to the privileges of a given class.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Social status

To speak French like or better than French people earns an individual recognition as being able to outgrow the subaltern culture and integrate into the master’s one.

Today's growing demand in the Maghreb for learning English does not constitute a departure from this belief. Rather, as with French, it speaks to a desire to ape native speakers in another language in order to gain social status at home. To learn to speak English now is to be ahead of the curve when it comes to gaining the advantages of a privileged social class.

Another issue associated with the debate on language in Maghreb societies is in academia.

It is puzzling how disconnected the academic research in language departments is from the needs of Maghreb societies, with PhD topics revealing a serious error of perspective. Instead of generating the expertise needed to understand the culture, politics, arts, and history related to the studied language, dissertations are generally about displaying how skilful the candidates are in imitating the native speaker of this language.

It never seems to be a question of translating the content of these dissertations into a national local language, which would constitute a linguistic space where a researcher meets society, where the individual talent meets tradition.

Nothing distils this better than American author Ursula K Le Guin’s wonderfully articulated feeling of dispossession. "The explorer who will not come back or send back his ships to tell his tale is not an explorer, only an adventurer; and his sons are born in exile," she wrote.

Indeed, language learning in the Maghreb context is less about telling a tale about the exploration of the unknown than an adventure that leads to dispossession of reality; a reality in which one fails to engage.

A cultural exile

To avoid this state of cultural and linguistic exile, many Maghreb writers, poets and thinkers - such as Algeria's Rachid Boudjedra and Morocco's Bensalem Himmich, Taha Abdurrahman and Abdelfattah Kilito - felt the need to switch, entirely or partially, to writing in Arabic.

In the works of these postcolonial figures of Maghreb intellectual life, there are overt warnings against the fallacies of presupposing the acquisition of a foreign language as a way to trigger economic, scientific and cultural development. They conclude that, while a foreign language can give society a whiff of the outside world and capture the cleverness of the present moment of history, it can never be a substitute for a native language's ability to kindle the sparks of genuine creativity.

They all seem to agree on the need to anchor the wisdom and knowledge that flow through foreign languages in a traditional linguistic soil. This constitutes the basis for a strong sense of being oneself, of identity, of being home.

However, the question of language remains unsolved inside Maghreb societies. Most people in the Maghreb are schooled in a sort of multilingualism that turns them into "wordless" beings, unable to relate to their own reality through language. The impact of this wordlessness is very evident in parliamentary debates, which reflect unparalleled levels of intellectual misery.

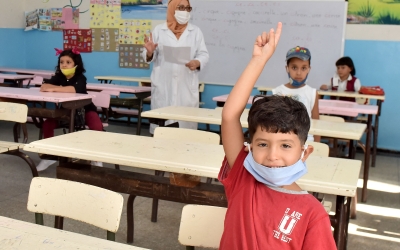

If the gap between the mother tongue and the language of scholarly communication remains unbridgeable in the Maghreb intellectual context, it is because of the failure of the education system to meet the needs of young people by providing them with a solid language training.

To get around this problem, some intellectuals play up the impact of the French language, thus concealing the genuine problems of illiteracy and its corollary inability to accommodate concepts, knowledge or technology gleaned in other cultural spaces and linguistic contexts.

The real concern today is that a substantial majority of Maghreb people have difficulty reading, writing and speaking confidently in any language.

A crumbling system

In this context, opting for English - or any other language - is not a panacea for all the ills of Maghreb societies. The problem is with the crumbling school system, which does not provide the schooled generations with the opportunity to reach the limit of their potential in learning French or any other language.

To say that French is not fit for science, technology or God knows what, amounts to concealing the poor quality of education. Perhaps a good mastery of French is even an asset to acquiring English. Maybe those who know French are better equipped to learn the nuances of the English language than those who do not.

Arabic is the language to entertain a sort of poetic sense of identity

In many respects, French is, for a whole class of intellectuals, still a kind of mother tongue in which new concepts are grounded. It is an unavoidable stepping stone to other European languages.

For others, it is the legacy bequeathed from the coloniser and should be abandoned. Arabic is the language to entertain a sort of poetic sense of identity; it is supposed to link one to the rhetoric of revelation. Berber is a spoken indigenous language that fights its way through towards acceptance as a written language.

It is an oversimplification to frame the conflict as one between French and English. The question of language in the Maghreb is a question of diversity. This can be crippling or enabling, depending on political will, strategic thinking, and planning.

Ultimately, what is needed is the genuine reform of the way languages are taught in the education system.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.