Michael Ratner: The Jewish lawyer who fought for Muslims and the US constitution

Rabbi Michael Lerner, eulogising Muhammad Ali, whom he knew since their peace activism against the Vietnam war, said: “The way to honour Muhammad Ali is to be Muhammad Ali today.” What Rabbi Lerner did in his speech was speak truth to power and strive for a better world by focusing on the common good. Much like “the Greatest” himself did throughout his life.

Over the years, I have come across many non-Muslims from various faith and non-faith traditions who have been in the forefront of standing up for Muslims and their constitutional rights. But given the tensions generated by the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, there is something especially significant when Jewish voices fight for Muslim rights.

Just as there are some Muslims who harbour anti-Semitism, there are also some Jews (and others) who fan the flames of Islamophobia. I am certain that this is not a big secret to most readers. What is less known and poorly celebrated are the instances when Muslims and Jews have protected and defended each other. In campaigning for human rights, civil rights and defending Muslims over the past three decades or so, I have had the honour of meeting or being exposed to Jewish individuals who have gone above and beyond. In fact, in my experience Jewish people have been the overwhelming leaders when it comes to civil rights and social justice issues.

One such individual I had the good fortune of making a brief acquaintance with was Michael Ratner. The champion of the oppressed passed away from cancer at the age of 72 in Manhattan on 11 May.

Ratner, the son of Jewish immigrants from Russia, is perhaps one of the most influential Jewish sons in the realm of human and civil rights in the last two decades in North America. Born in Cleveland in 1943, many say the social justice soldier inherited his “empathy gene” from his parents, who were both well known for their philanthropy and social activism. It is reported that his mother refused to enter a Florida airport because it was racially segregated and his father once gave his shoes to a homeless man. The apple clearly didn’t fall far from the tree.

Much like the boxing great, Ratner did not pull any verbal punches. In 2002, Ratner told the New York Times: “A permanent war abroad means permanent anger against the United States by those countries and people that will be devastated by US military actions. Hate will increase, not lessen; and terrible consequences of that hate will be used, in turn, as justification for more restrictions on civil liberties in the United States.”

Like many, the activism torch was first ignited during his student days at Columbia Law School when, while protesting against the Vietnam War, he was pushed to the ground and beaten up by police. In retrospect, the world should thank the cop(s) who attacked him, because they unleashed a warrior for the oppressed. Indeed, he later told the New York Times: “Events like this created the activists of the generation and I never looked back; I declared that I was going to spend my life on the side of justice and non-violence.”

After a brief stint with the NAACP Legal Defense Fund, Ratner quickly found his home at the Center for Constitutional Rights (CCR), which he joined as staff attorney in 1971. He would spend the next four decades at the CCR. Founded in 1966 by Benjamin Smith, William Moses Kunstler, Morton Stavis and Arthur Kinoy (the latter three are Jewish and giants of civil rights and social justice in their own right), the CCR was a scrappy civil rights outfit that always fought above its weight. Ratner would go on to serve as its legal director from 1984 to 1990 and its head from 2002 to 2014. Thanks to Ratner’s chutzpah, intellect and vision in taking on the world’s most powerful on behalf of its weakest, the CCR's profile rose significantly.

He oversaw litigation that, among other things: checked government complicity in kidnapping and torture of terror victims (rendition); voided New York City’s wholesale stop-and-frisk policing; freed HIV+ Haitians held in Guantanamo Bay in 1993; represented Julian Assange and WikiLeaks in exposing abuses and ensuring access to information; and argued against the constitutionality of warrantless surveillance, torture at Abu Ghraib, interference in central America and waging war in Iraq without congressional approval, etc. In the process he is arguably one of the few, if not the only person, to have sued three US presidents during his legal career: Ronald Reagan, Bill Clinton and George W Bush.

An article such as this cannot do justice to the long list of victories - both his and the CCR's under his leadership - and their impact on society. But we can certainly conclude that in taking on the most powerful on behalf of the weakest, Ratner fulfilled the promise he made after his beat down in 1968, to strive to make the world a better place.

David Cole, a former staff attorney at the CCR and now law professor at Georgetown, predicted that his friend would be best remembered for persuading the Supreme Court to recognise that Guantanamo prisoners had the right to habeas corpus. As Ratner later told Mother Jones: “This was a case that was regarding a fundamental principle, going back to the Magna Carta in 1215, about the right to have some kind of a hearing before you get tossed in jail.”

The case was of historic significance as well as it was “the first Supreme Court decision in history to rule against a president in wartime regarding his treatment of enemy fighters,” says Professor Cole.

Like most activist-oriented lawyers, I had heard about Ratner and admired his work. But his stature rose in my mind significantly when he reached out to me in 2003 after my father, Shaikh Ahmad Kutty, and his colleague, Shaikh Abdul Hamid, both imams, where religiously profiled by US authorities during a speaking trip to the United States.

They were taken off their flights, interrogated, detained in jail and then returned to Canada after a public outcry. He had read the reports and called to show his support. We chatted briefly about racial/religious profiling in the United States and how he was deeply disappointed in the direction the country had taken post 9/11. He also noted that unfortunately, the public was not ready at the time to challenge the government due to the national security climate of fear.

He used the courts but was cognisant of the role of the court of public opinion in taking on injustice. Indeed, as one of his good friends, Vincent Warren, noted, Michael “sometimes won in court, but always won in the court of public opinion”.

A few years later, I approached him to invite him to speak as a keynote and to be recognised as an awards recipient at a civil rights event I was helping to organise. His heavy workload and schedule did not permit. What struck me though was that he still took the time not only to respond but showed genuine interest, which he demonstrated by going the extra mile in directing me to his colleague at the CCR, David Cole (another titan of civil rights).

While many have celebrated his legal victories, we have seen less about his work on behalf of Palestinians in Gaza and the West Bank. He was a vocal critic of the treatment of Palestinians and spoke out against Israeli violation of International law. Over the last couple of years, he helped found Palestinian Legal, which was set up to defend the rights of Palestinians to protest.

“Getting to know Palestinians was very important on [my] adventure,” he said. Family and friends say he was determined to make sure others had the same experience. Later he would demonstrate his willingness to stand up for his beliefs (no matter how unpopular) when he quit from the board of his alma mater, Brandeis University, over the school’s suspension of ties to Palestinian Al Quds University.

He also served as president of the National Lawyers Guild and the European Centre for Constitutional and Human Rights. As if his plate was not full enough, he hosted radio shows and wrote a number of books including The Trial of Donald Rumsfeld: A Prosecution by Book; Against War in Iraq; and Guantanamo: What the World Should Know.

As Ratner incisively noted: “There is not the same sense of strength in struggle that you can change things, not as there was in the '60s and '70s. You get to the point where you have a very conservative government and you feel like you are only a flickering light. But we have to keep the light lit.”

Indeed, as Rabbi Lerner said at Ali’s funeral, today more than ever we need people who will stand up for the oppressed. We need more people who will take on Goliath and stand for justice no matter what the consequences. We need more Ratners to keep the flame burning. RIP counsellor.

- Faisal Kutty is counsel to KSM Law, an associate professor at Valparaiso University Law School in Indiana and an adjunct professor at Osgoode Hall Law School of York University in Toronto. You can follow him on Twitter @faisalkutty

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

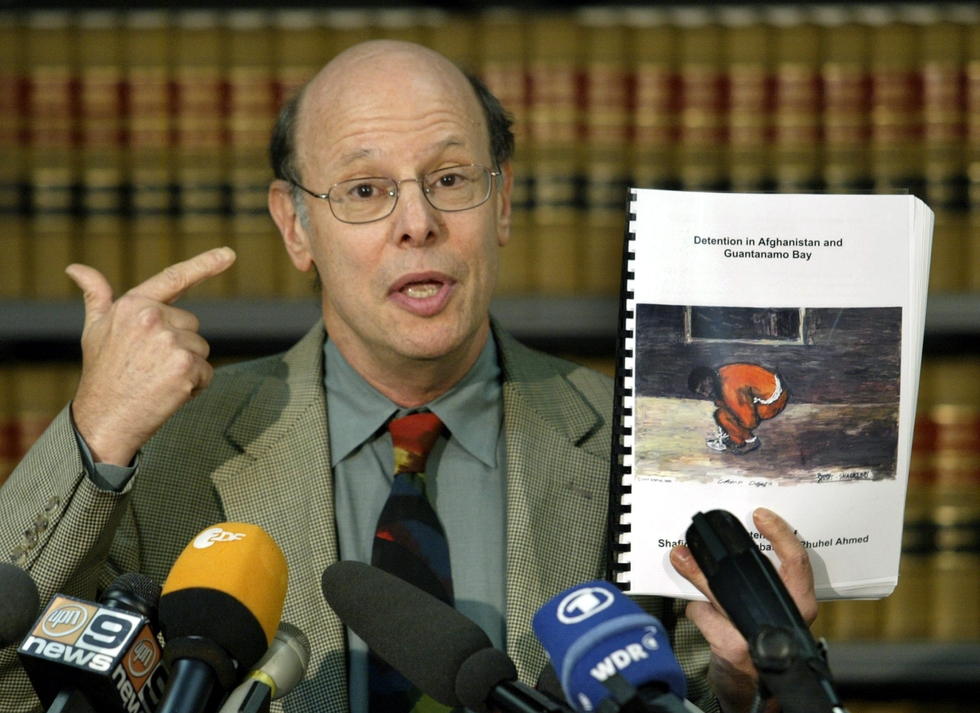

Photo: Michael Ratner, holding report of life at Guantanamo Bay prison, in New York on 4 August 2004 (AFP).

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.