Mohammad bin Salman's reign of terror will not make Saudi Arabia stable

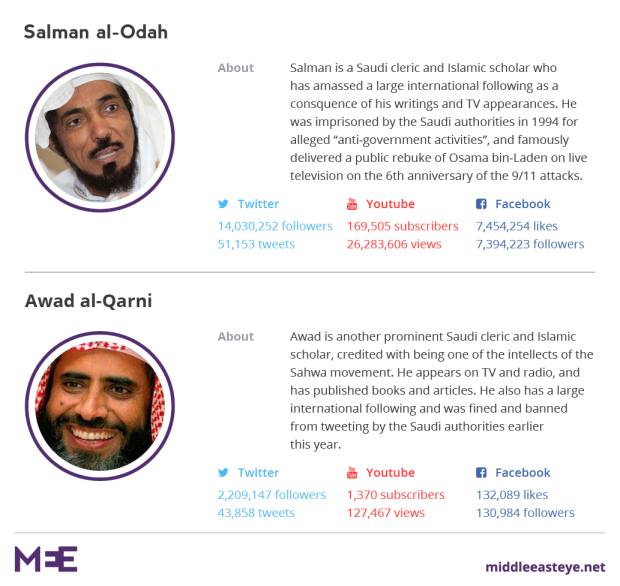

The Saudi regime recently detained veteran Salafi sheikh, Safar al-Hawali, 68, who has serious health problems. Other members of his family were also sent to prison. The sheikh joined his old comrade of the 1990s, Sheikh Salman al-Awdah, who has been in detention since September.

They were both the leaders of an opposition movement that came to be known as the Sahwa (awakening) following a mobilisation in 1990 when the regime invited the US and other foreign and Arab forces to defend it against an imminent invasion by Saddam Hussein of Iraq. But the two sheikhs differ dramatically in their interpretations of Islam, gender, politics, relations with the West, and the future of the Muslim umma.

Silencing public sphere

While al-Hawali aspires to return to the original ideal of the first Saudi state, closely faithful to the teaching of the 18th-century founder of Wahhabiyya, Mohammed bin Abd al-Wahhab, al-Awdah aspires towards a modern Muslim polity, with a constitution and a representative government. One with a foot in the past and one with an eye to the future.

Detaining their other colleagues such as Awad al-Qarni and less well-known Sahwis, Crown Prince Mohammad bin Salman may have now succeeded in silencing the Saudi public sphere and muting dissenting voices.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Since becoming crown prince, he has spread terror across many constituencies - the royals, the economic elite, the liberals, the non-ideologicals, tribal figures, and most recently women activists. But rather than strengthening his position, this appears to leave him standing on shaky ground, unable to create a coalition to rule by consent rather than terror.

Imprisoning the old pillars of the Saudi state religion will cost Mohammad bin Salman and his western allies a high price

Many in the West may cheer Mohammad bin Salman's detention of Islamists, often dubbed as radicals, regardless of the diversity of both their interpretations and strategies to pursue their religious and political goals. This is a misguided endorsement of a policy that had backfired in the past as it produced only short-term solutions to a profound political problem that breads radicalism.

Islamist goals often include a plethora of aspirations, for example, the Islamist state or caliphate, application of Sharia, Islamising the public sphere, empowering women according to their own agenda, pursuing an "Islamic" foreign policy, seeking Islamic economics, and making Islam and only Islam the reference framework for conducting almost all the affairs of the Muslim umma.

Whether we agree with these objectives or not, detaining those who promote them can only increase the popularity of such projects, drive them underground, and make them explode in our faces when we think they have been extinguished.

The religious and the secular

Notwithstanding these broad aspirations, Islamists differ so much among themselves that arguably their internal theological and political differences are so pronounced as to be irreconcilable.

While we are accustomed to look at the religious and the secular as two separate and sharply different categories, thus making Islamists the antithesis of secular activists, the reality is that many Islamists are definitely closer to secularists than, for example, jihadis.

Moreover, so-called Islamic terror is not more terrorising than some secular projects that led to the eradication of minorities, crushing of freedoms and silencing dissent. If the Islamic State (IS) annihilated ethnic and religious minorities in the Middle East, secular leaders have contributed to ethnic cleansing and discrimination along sectarian, ethnic and national divides.

The so-called Islamic terror is not more terrorising than some secular projects that led to the eradication of minorities, crushing of freedoms and silencing dissent

From Ataturk of Turkey to the shah of Iran, and the various Arab presidents and monarchs, we have authoritarianism masquerading as secular projects to modernise nations. But in reality, the terror was common and, in some instances, no great difference can be identified between some religious and secularist projects.

The aim has always been to rule without consideration to diversity and human rights. The latest players in this game, such as Mohammad bin Salman, can give women the right to drive and allow them to go to concerts, stadiums and theatres, but he can also put women activists in prison.

But calling many Islamists "radical" is an all too easy way to tar them with the same brush. This creates a wide net in which they are lumped together to facilitate their marginalisation and even justify their detention, torture and beheading. The label "Islamist" itself, together with the earlier labels of "fundamentalist" and "political Islam" remain ambiguous and debated in academic circles.

The most vigorous and widespread are those who think themselves as missionaries such as the Tablighis, who operate a transnational network of determined preachers. The personal may be at the heart of the political, yet not many observers believe that the pursuit of personal piety is simply a form of acceptable religiosity that has nothing to do with community building.

Our rigid categories of the religious and the secular remain hostage to their European Enlightenment heritage and fail to explain the intersection of the two in every aspect of life even in the West. But Western modernity forces us to see them as worlds apart.

A real transformation

Other so-called Islamists do indeed have an obvious political project like any political party across the globe although they differ in their strategies to pursue them. While many are happy to participate in elections and sit in toothless parliaments, others seek a real transformation of political institutions from within to correspond to an Islamic ideal.

Yet another group may pursue armed struggle after giving up on the efficacy of peaceful mobilisation, charitable work, education and preaching. They condemn their brethren who do engage in what they deem futile and counterproductive strategies.

Those Islamists who subscribe to armed struggle may not necessarily start as violent rebels. They may evolve to adopt indiscriminate violence after reaching the conclusion that dictatorships are beyond reform and redemption. In fact the most violent amongst them are the ones who have first-hand experience of how far dictatorships can go in inflicting violence on activists, from torture to rape.

Many Saudis intensified their violence and terror in 2003-2008 against the regime and foreigners after having suffered torture in Saudi prisons. This is not to justify terrorism but to point to fertile conditions in which such terror is cultivated. Prisons have always been and will remain incubators of future violence, although they can potentially be places for redemption and rethinking of political projects among prisoners of conscience and dissidents.

A suicide strategy

Calling all Islamists radicals is a misnomer. Moreover, not all radicals are violent. European history attests to how in a previous era societies and governments tolerated anarchists, radical thinkers, and uncompromising ideologues. As long as they did not preach violence as a means to an end, they were allowed to continue to dream radical utopias.

However, Mohammad bin Salman refuses to believe that there are visions other than the ones that management consultancy firms prepare for him. Once he adopts them as visions, they become sacrosanct, and criticising them becomes an act of treason against the future king.

In such an atmosphere, Safar al-Hawali’s most recent book, Muslims and Western Civilisation, is bound to be worse than any revolutionary manifesto distributed by an underground cell determined to topple the regime.

The book is a combination of theological interpretations and history, surveying relations between Muslims and the West. Yet Mohammad bin Salman is determined that thorny issues are not written about and those who discuss them are better sent to prison.

The West should not be blinded by this unprecedented terror in Saudi Arabia. Neither Mohammad bin Salman nor his vision will deliver the stability and the security that Western government think the Saudi regime is capable of delivering.

Imprisoning the old pillars of his state religion is a purge that will cost him and his allies a high price. The short-term silencing of dissent is bound to be a suicide strategy in the long term.

Allowing radicals to vent their anger in books is definitely better than pushing them to carry arms.

- Professor Madawi al-Rasheed is a visiting professor at the Middle East Centre at the London School of Economics. She has written extensively about the Arabian Peninsula, Arab migration, globalisation, religious transnationalism and gender. On Twitter: @MadawiDr

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Photo: Saudi Crown Prince Mohammad bin Salman attending a meeting in Mecca to discuss the economic crisis in Jordan on 11 June 2018 (AFP)

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.