Morocco: Ten reasons why Mohammed VI's reign has lasted 20 years

Former Moroccan King Hassan II once answered a question about his relationship with the crown prince in these terms: “The style changes with the man. I have my own, so does he.” It was a way of saying his son’s rule would be different from his own.

Indeed, the two men are obviously different, but their modes of governance have a common ideological origin that privileges the personification of government, the concentration of powers, and the political domination of opponents.

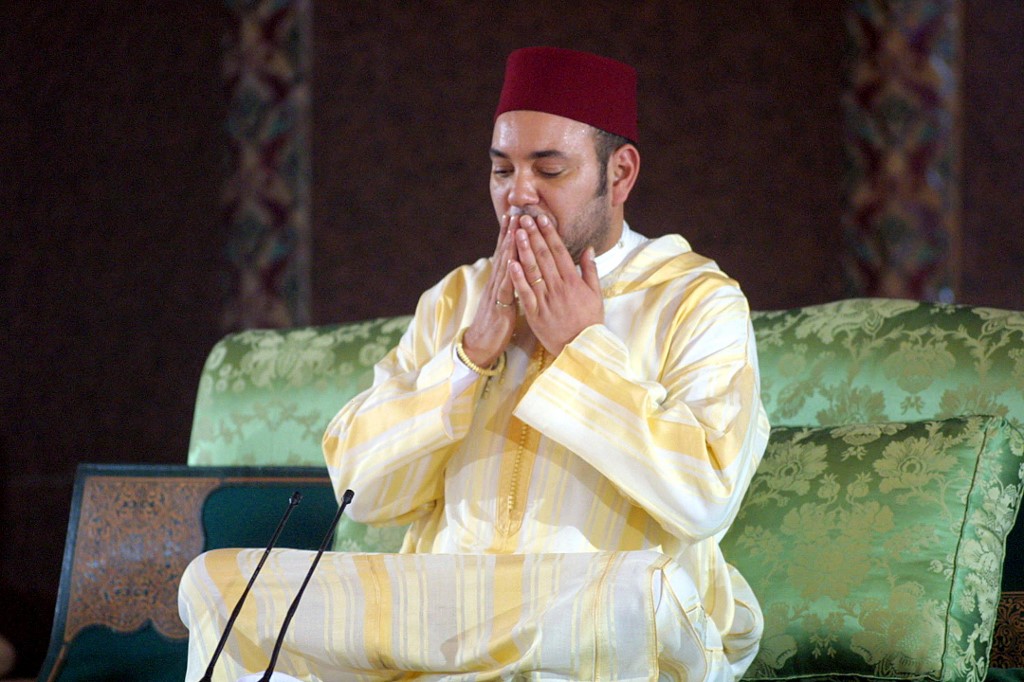

Thus, despite numerous promises of reform, King Mohammed VI’s reign eventually took the path of a “corporatist authoritarianism”, mitigated by sporadic attempts at democratisation.

Mohammed VI, Hassan II’s oldest son, inherited the throne upon his father’s death. Born in 1963 in Rabat, Mohammed VI is the 23rd monarch of the Alawite dynasty, remaining in power for two decades despite the country’s grave socioeconomic and political crises. Ten factors can help to explain the dynasty’s resilience.

1. Patrimonial power

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

In 1999, Mohammed VI dismissed the powerful former interior minister, Driss Basri, in a sign he wanted to break away from the autocratic reign of his father and assert his own power over the state apparatus.

Twenty years later, the king is painstakingly trying to free himself from the weight of a patrimonial tradition in which “Muslim subjects” pledge allegiance to their king. Last month, the palace issued a statement noting that it did not want “special” celebrations for Throne Day on 30 July, a date commemorating the king’s accession to the throne.

Yet, it is hard to believe the king is not adhering to the patrimonial mode of governance. Since 2011, Moroccan authorities have been particularly zealous about gathering crowds for the allegiance ceremony, showing that the regime remains committed to perpetuating the tradition that preserves the monarchy’s historical legitimacy.

2. Promises and false hopes

“Change in continuity” is one of the political maxims advocated by Mohammed VI, which generated much hope for reform. Indeed, as soon as he became king, large segments of the Moroccan population thought he would break notably from Hassan II’s autocratic reign.

The youth of the new monarch, his openness to civil society, and his empathy with marginalised populations seemed to herald a democratic future for the kingdom. Back then, numerous observers were betting on change “from above” that would lead to regime democratisation.

Instead, after 20 years, the young king has been caught up in the history of the Alawite sultans who considered themselves as “the shadows of God on earth”.

3. Royal fortune

As soon as he ascended to the throne, Mohammed VI revealed himself as a shrewd businessman. Very early on, he restructured the North African Omnium Group (ONA), appointing Driss Jettou, the former CEO of Siger, a royal family holding, as its new head.

Two years later, Jettou became prime minister, angering the Socialist Union of Popular Forces, which won the 2002 legislative elections. In 2010, the ONA merged with the National Investment Company (SNI), itself majority-controlled by Siger, and became the kingdom’s main economic player, now called Al Mada.

According to Forbes magazine, Mohammed VI’s wealth is estimated at $5.7bn. At the same time, the population is getting poorer. The king himself admitted in a speech that “the country’s model of development is inadequate and has become exhausted … a new development model is urgently needed”.

4. Consolidating security and judicial institutions

The regime of Hassan II relied on a brutal security apparatus to intimidate and silence political opponents. Apparently willing to break with his father’s heritage of repression, upon assuming the throne, Mohammed VI emphasised the “protection of liberties and the preservation of rights”.

This did not take into account the tenacity of the security establishment, whose officials would soon resume their old authoritarian practices. After the deadly Casablanca attacks in 2003, the state arbitrarily arrested thousands under the pretext of counter-terrorism; the following year, the International Federation of Human Rights denounced Morocco’s “blatant violations of human rights.”

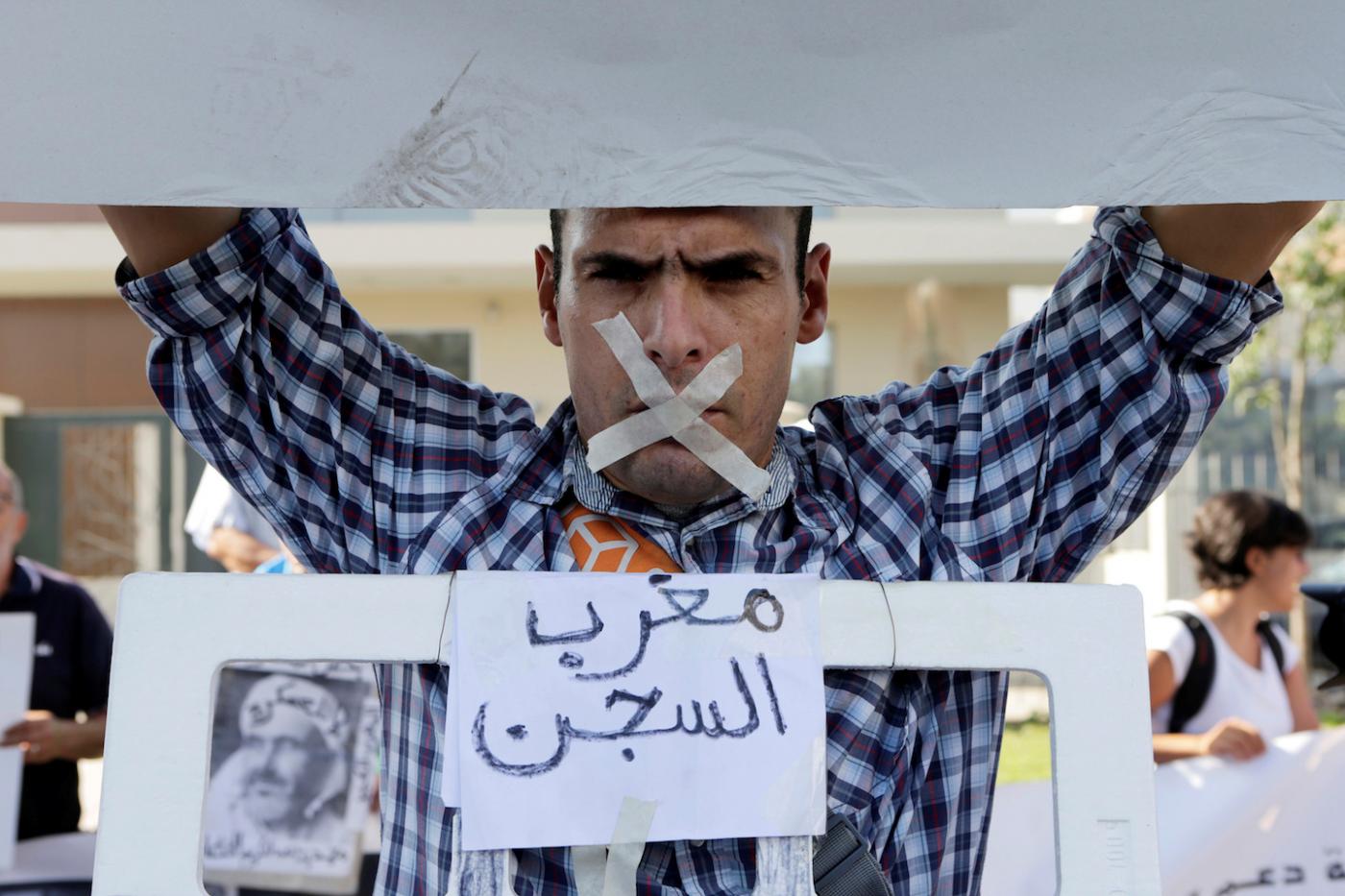

After the Arab Spring, the regime of Mohammed VI aimed to neutralise popular protests. Secret service chief Abdellatif Hammouchi orchestrated the brutal repression of the Hirak protest movement, which started in the Rif after the death of a fish seller.

Far from the principle of “separation of powers”, the king also controls the justice system: he appoints the justice minister and the head of the Supreme Council of the Judiciary, established in 2017. In the unjust trials of Hirak activists, among other problems, the courts did not respect the rights of the defendants.

5. Instrumentalising religion

The king is presented as the descendant of the Prophet, endowed with a “divine right” incarnated in the oath of allegiance - a moral contract that binds the sultan and his subjects, who are supposed to obey him in exchange for his protection and benediction.

After the 2003 Casablanca attacks, Mohammed VI initiated a reform of the religious sphere, aiming to “fight intolerance and extremism”. This increased his capacity to neutralise Islamists, especially Salafists. At the same time, secularisation initiatives enable the monarch to trade his role as a spiritual leader for that of a political leader with full powers.

The religious dimension of the monarchy is often associated with propaganda operations that highlight the moral dimension of the monarch’s empathic, charitable and noble soul. Commonly called “the king of the poor”, Mohammed VI has staged public events where he interacts “informally” with his people.

In 2005, the king launched the National Initiative for Human Development, aiming to improve living standards. In reality, its main purpose was to compete with Islamists in the domains of social care and charities. Today, the kingdom ranks 123rd for human development, out of 189 countries.

6. National identity

The king of Morocco is considered a symbol of Morocco’s national unity and the protector of the kingdom’s territorial integrity.

In 2004, he launched the Equity and Reconciliation Commission to reconcile Moroccan victims of human rights abuses during the reign of Hassan II with the state - but it was criticised for failing to examine the state’s responsibility for its crimes against regime opponents.

The 2017 Hirak uprisings in al-Hoceima indicate the persistence of Morocco’s national identity crisis. The popular protests were brutally repressed and the leaders incarcerated.

Shaken, the monarchy quickly tried to protect itself by denouncing and stigmatising the “separatist excesses” of the Rif activists - trying to present them as a threat to a national unity.

In 2011, Mohammed VI responded to the Arab Spring protests in a proactive manner, offering a “royal” revision of the constitution, which left the full powers of the monarch intact, despite some undeniable concessions. The regime hyped the threat of chaos and civil war in its efforts to stop the February 20 movement.

In 2017, the Hirak in the Rif marked the end of the “Moroccan exception” myth. Just like numerous Arab authoritarian states, the regime would soon revert to police violence and judicial repression to tame the Rif activists and deter other possible protests.

7. Neutralising political parties

The monarchy has always viewed political parties as a danger to the regime, and there is also a strategy of manipulating political elites. The Islamist Justice and Development Party has currently managed to position itself as an indispensable ally, the only party strong enough to help the monarchy resist the protests and the crises tearing the country apart.

But one should not forget that the palace can at any time decide to rebuild ties with former adversaries, as has been done with members of the Socialist Union of Popular Forces.

To maintain control over the country’s political life, the monarch can reactivate old alliances in order to weaken more recent ones. For example, Aziz Akhannouch was selected as the new head of the National Rally of Independents party, provoking a political stalemate that accelerated the royal decision to dismiss the former prime minister, “troublemaker” Abdelilah Benkirane.

8. Co-opting intellectual and media elites

If the monarchy has always strived to co-opt political elites, Mohammed VI has surrounded himself with a legion of loyal partisans from political, intellectual and activist circles.

The regime has somewhat opened up politically. Yet freedom of expression is still lacking, especially in journalism, as the media is largely controlled by the regime or by businessmen close to the king.

Media propaganda, hidden behind the misleading label “independent press”, is often supported by the authorities, who never hesitate to reward, with juicy public subsidies or advertising money, the press organs that have been loyal. By contrast, the regime is merciless with critical journalists.

Certain academics, journalists and NGO members have no problem defending the regime’s positions and decisions, thus reducing to almost nothing the space for contradictory debate, which is necessary for democratic life.

9. Diplomatic pragmatism

Mohammed VI has oriented the country’s foreign policy towards the African continent, preparing the terrain for a political return to the African Union. After a three-decade absence, the regime indeed returned to the union in 2017, in part aiming to improve Morocco’s messy policy on the Western Sahara.

Internationally, the king has always promoted a diplomacy grounded in pragmatic multilateralism. Loyal to his alliance with France, Mohammed VI has nonetheless solicited the help of other world powers, from Russia to China.

Morocco’s king has emphasised his status as “commander of the believers”, aiming to gain control of the religious leadership - a strategy congruent with US policy, which seeks to contain the rise of Shia Islam in the Middle East. Morocco has already severed diplomatic relations with Iran, and the country had representation at the Manama “deal of the century” conference on the Israel-Palestine conflict.

In 1986, Hassan II was already talking about the invaluable political opportunities of “economic normalisation” between Israel and Arab countries. More than three decades later, the “deal of the century” is gradually resuscitating the same idea: that peace in the Middle East will require regional economic development. This philosophy echoes the convictions of Mohammed VI.

10. The king's ultimate refuge

Whenever he is seen in public, Mohammed VI offers the image of a king profoundly attached to his family, especially after his undeclared divorce from Princess Lalla Salma.

Some of his close collaborators say his relationships with his sisters and nieces are particularly important to him. If his family brings him comfort, solace and a sense of security, despite the turmoil of the royal court, it is probably in the business world that the king finds his true vocation.

As a good manager, he has always been able to find sound and profitable financial investments, though some transactions have been dubious. But he has been successful at building his fortune, even during global economic crises. Yet, this has not translated into social and economic development for Morocco, nor helped to complete the democratic transition process.

The path forward

It has been two decades since Mohammed VI’s accession to the throne. Morocco’s socioeconomic crisis is only getting worse, and popular protests are expanding. Some are no longer shy to directly blame the regime.

To respond to this volatile situation, the king could multiply initiatives to restore the image of the monarchy. He could go so far as to pardon Rif leaders, in hopes of containing popular discontent. But would it be enough for Moroccans to forget the use of torture and the extravagant trials against activists?

Will the monarch be clairvoyant enough to actually leave past policies behind? Will Mohammed VI be willing to politically reform the regime and make an alternative option possible?

That is the only path that could allow the king to stay in power, within a new democratic framework grounded in citizenship and the rule of law.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

This article has been translated and condensed from the original, which appeared in the MEE French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.