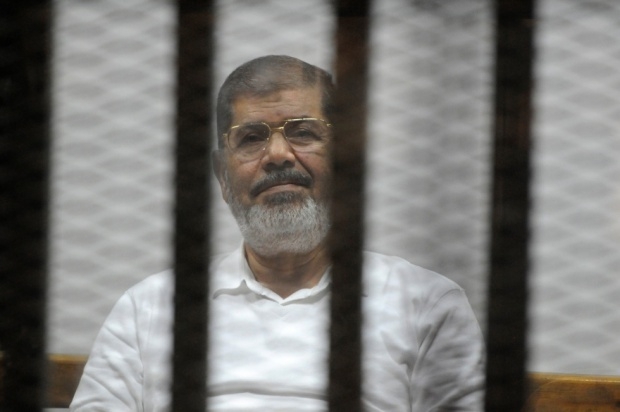

Morsi verdict may fuel an endless cycle of violence

A Cairo Court on Tuesday upheld the death sentence against deposed President Mohamed Morsi over jailbreaks that occurred during the 2011 uprising. Death sentences were also confirmed for five Muslim Brotherhood leaders, including the group’s supreme guide Mohamed Badie, and 94 others in absentia. The court also upheld life sentences for another 20 prominent members of the now-outlawed Muslim Brotherhood in the same case.

Earlier in the day, the same court had upheld life sentences for Badie and the former president in a separate case related to charges of “conspiring with foreign groups”. Fifteen others were also given life sentences while death sentences were upheld for 16 defendants (13 of them in absentia) in what is referred to by Egyptian media as the “espionage case”. The convictions in this second case were based largely on the testimony of security agents that Morsi and the other defendants had “leaked classified information to Iran, Hamas and the Lebanese Shiite group Hezbollah”.

Morsi is already serving a 20-year jail term in a third case for allegedly “ordering the torture and arrests of demonstrators” during his one-year term in office.

The latest death sentences, initially handed down to the defendants in mid-May, had been referred to the Grand Mufti - Egypt’s highest religious authority - for approval. The defendants’ lawyers have said they will appeal, a move that would leave the final decision to the High Court.

Confirmation of last month’s verdict drew an outcry from human rights groups and condemnation from members of the Muslim Brotherhood. The official website of the outlawed Muslim Brotherhood called the ruling “illegitimate,” vowing “Those responsible for the verdict would be held accountable for the crime.” The statement regretted that “the violations” committed by the current regime was “forcing youths to resort to violence”. It was unclear whether this meant a potential escalation in the violence against the military and the police in Egypt in the days and weeks to come. Militant groups supportive of the Muslim Brotherhood have claimed responsibility for attacks carried out against security personnel during the past two years while the Muslim Brotherhood has insisted it will continue its struggle through peaceful means.

Last week, however, in a possible sign that the militants may be planning to widen their insurgency, two militants were killed in an attack, reportedly aborted by police, outside Karnak Temple in Luxor.

Meanwhile, Sondos Asem, who had worked as foreign press secretary under Morsi and one of the people sentenced to death in absentia in the “espionage case,” criticised Tuesday’s verdict, describing the judiciary as “completely politicised”. In a message posted on her Facebook page, she warned that the situation in Egypt was “deteriorating” and that the lives of many youth-revolutionaries were at risk.

Human Rights Watch (HRW) denounced the trials in the two cases as “flawed,” and the charges against the defendants as “politically-motivated”. In a statement published on its website shortly after the verdicts were announced, the rights group said the trials had been compromised by “due process violations” as there was “no evidence - other than the unsubstantiated testimony of military and police officers - to support the convictions of the defendants in both cases”. Moreover, HRW called for a retrial for the defendants in proceedings “that meet international fair trial standards”.

Echoing the call for a retrial, Mohamed el Messiry, a researcher with Amnesty International, also lamented what he called the ( Egyptian judiciary’s) “bias” against the Muslim Brotherhood and the lack of accountability for security forces. Speaking to the Global Post on Tuesday, he cited police violence that had resulted in the deaths of “more than 1000 people in a single day on August 14, 2013,” reminding that those responsible had escaped justice.

The reaction on the streets to the latest mass death sentences was far more subdued. Not surprising, the country has been deeply polarised since Mohamed Morsi was ousted by military-backed protests in July 2013 and there is widespread animosity towards the Muslim Brotherhood, often blamed by Egyptians for the ongoing violent attacks in the country.

The Egyptian pro-government media has fuelled the hatred against the Islamist group through its blind support for the “war on terror” and its persistent vilification of the former Morsi government. Since Morsi’s overthrow, supporters of the military-backed government that replaced him have tacitly acquiesced to the killings of hundreds of Muslim Brotherhood supporters by security forces, the imprisonment of tens of thousands more and, reportedly, widespread torture and abuse of detainees at police stations and in prisons. Meanwhile, the majority of Egyptians have remained silent in the face of mass death sentences handed down last year to more than 1000 people, the majority of them Brotherhood sympathisers.

Many appear to have “forgotten” or have chosen to overlook that a fact-finding commission appointed in April 2011 (a few months after Mubarak was forced to step down) by then-Prime Minister Essam Sharif and headed by Cairo’s Court of Cassation had blamed Mubarak’s Interior Minister Habib El Adly for the jail break-ins. He had given orders to senior officers to open up the prisons and allow prisoners (including thugs and criminals) to escape in a bid to create chaos on the streets and, thus, force the revolutionaries off the streets, the commission had revealed at the time.

A police officer interviewed by TV talk show host Mahmoud Saad on Al Nehar private channel shortly after the revolution had admitted he had received direct instructions to “free the prisoners”. According to an article published in Al Ahram Online in July 2011, the sister of Major General Mohamed El Batran, a senior officer who was shot and killed at El Kat Prison on 29 January, 2011, told the news site he had been deliberately killed by a fellow officer for refusing to obey orders from senior commanders to allow prisoners to escape.

More than four years on all that remains are sketchy details that have become even more blurred as a result of, among other things, a deliberate media campaign that has persistently demonised the Brotherhood. Despite marginalisation, the Muslim Brotherhood, a traditionally underground group, has over decades, survived several crackdowns by successive governments.

Attempts to mercilessly crush the opposition yet again may drag the country into a seemingly endless cycle of violence and counter-violence. Such attempts may also radicalise the opposition, forcing it to align itself even more closely with more violent militants. If that happens, there will be neither peace nor stability …and certainly no winners on either side.

- Shahira Amin is a Cairo-based independent journalist who has won several international awards including Spain's Julio Anguita Parrado Journalism Award in 2012 and the Global Thinkers Forum's Excellence in Promoting gender equity Award 2013.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Photo: Cairo court upholds death sentence for Egypt's former president Mohamed Morsi (AFP)

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.