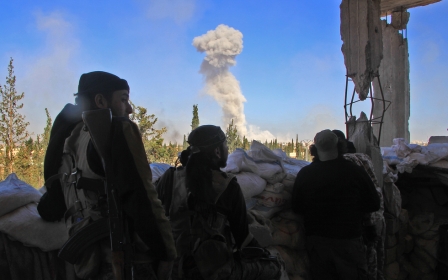

The new UN chief inherits poisoned chalice to solve Syria crisis

On 1 January, Antonio Guterres, a former Portuguese prime minister, will become the new United Nations secretary-general.

Following the organisation’s failure to end the fighting in Syria and the beginning of the Trump administration in the US in late January, Guterres' ability to make the UN relevant in Syria beyond humanitarian assistance will be seriously constrained.

The Portuguese landed the top diplomatic job after having built a solid reputation of transparent governance and responsible administration as chief of the UN High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR) from 2005 to 2015.

Russia’s unshaken diplomatic and military support to Syrian President Bashar al-Assad has raised tensions at the council to levels unseen since the Cold War

During his last years at the helm of the UNHCR, Guterres sharply criticised Western governments for not doing their part to deal with the Middle East refugee crisis, the greatest migration emergency facing the world since the Soviet-Afghan war.

Since he left the UN 10 months ago, the situation in the region has become even more hopeless. The UN Security Council, the same body that displayed an unusual consensus by appointing Guterres, has been unable to agree on how to stop the appalling bloodshed of the Syrian conflict, the worst case of mass atrocities since the Rwandan genocide in 1994.

Russia’s unshaken diplomatic and military support to Syrian President Bashar al-Assad has raised tensions at the council to levels unseen since the Cold War. Moscow has already vetoed five security council resolutions on Syria in as many years - Russia’s last veto just a few weeks ago stopped a demand to immediately halt all aerial bombardments and military flights over the city of Aleppo.

Tight manoeuvre

In his first interview after being appointed as next UN leader, Guterres acknowledged that his biggest challenge will be Syria. He spoke about a "surge in diplomacy for peace" to break the deadlock that holds back the council to address a brutal conflict that could have killed nearly half a million people.

Yet according to Vitaly Churkin, Russia’s permanent representative to the UN, all the expectations created around Guterres are somehow pointless as Guterres will not be able to “do much” about the council, since he will not be in charge of it.

By supporting Russia’s backing of Damascus, the incoming Republican US administration may well be a game changer on the ground, but will not unlock the paralysis in the UN Security Council on Syria

Churkin’s unsubtle message emphasises the tight room for manoeuvre faced by UN chiefs to influence the council’s permanent members (the US, Russia, China, the UK and France). This narrow diplomatic space could shrink even further if Trump’s strategy in Syria boils down to merely following Putin’s winner-takes-all policy. For Trump, defeating the self-styled Islamic State (IS) is more important than getting rid of Assad. “

"I don’t like Assad at all, but Assad is killing ISIS,” said Trump during the second presidential debate.

During the campaign, Trump repeatedly stated his enthusiasm to work closely with Russia in the international scene. Once he takes over the White House, and if one is to believe Trump’s discourse, the only consideration that could prevent unambiguous US support of Russia’s policy in the country would be Syria’s oil and gas.

During his first months in office, Trump will be aiming to enjoy an undisturbed honeymoon with his counterpart in Moscow, so not interfering with Russia’s plans in Syria will be the priority. On its side, China will gladly go along with Putin and Trump in their resolute support to the Bashar al-Assad regime.

Danger of irrelevance

So when it comes to Syria, this may well be the new balance of alliances the UN chief will have to deal with in the Security Council. If this new normal materialises, the UK and France will be the only veto-power council members supporting moderate rebels and raising the issue of the mounting human toll caused by Assad and Putin air strikes.

By supporting Russia’s backing of Damascus, the incoming Republican US administration may well be a game changer on the ground, but will not unlock the paralysis in the UN Security Council on Syria. The UN, in spite of Guterres’ efforts, may well become even more irrelevant to ease the suffering caused by this grisly civil war.

Under the rarely-used "Uniting for Peace" mechanism, the UN General Assembly could step in. The mechanism means that faced with of a lack of unanimity amongst its five permanent members, "if the council fails to act as required to maintain international peace and security, the General Assembly shall consider the matter immediately and may issue any recommendations,” including the use of armed forces.

'Unity for peace'

In an informal meeting led by Canada and supported by 70 countries, the assembly was called to come together last month so that the special session needed to trigger the "Unity for Peace" procedure could be convened. Among other things, this session could mandate an investigative mechanism to gather evidence for use in a future criminal prosecution of serious crimes committed in Syria.

This follows an early appeal made by Staffan de Mistura, Ban Ki-moon’s special envoy for Syria, asking the assembly to take action “if the cessation of hostilities fails”. Some analysts have suggested that, after more than two years of continued frustrations and thwarted talks, de Mistura may have to go and give way to an invigorated mediator able to seize the "Guterres momentum".

If the new secretary-general and its special envoy are able to facilitate a lasting cessation of hostilities in areas controlled by Damascus and non-jihadist opposition groups, the agreement would have to include credible monitoring and compliance mechanisms and ensure that UN-coordinated humanitarian aid reaches the millions of people that need it. The Syrian government has routinely obstructed the delivery of cross-border relief assistance, contravening multiple council resolutions.

Guterres would also have to reduce to the essential the aid delivery deals done with relatives of ministers in Damascus, with which UN agencies have to work as part of their relief operations.

Ending impunity

As Guterres has already stated, he will try to ensure that war crimes are documented and impunity ended in Syria. The UN and the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW) just concluded that Syrian government forces used chemicals last year in an attack on the rebel-held city of Idlib.

'The need for a brave and decisive new secretary-general is literally a matter of life and death. In fact, many deaths'

-Carne Ross, former British diplomat

Furthermore, Washington is weighing further sanctions against Syria and a push for justice at the International Criminal Court, but both initiatives are now likely to fade away once Trump settles in Washington.

Whatever the future of the battled country will look like, a strong element of accountability will have to be part of the equation. Yet an abrupt focus on justice may hamper both efforts for an immediate halt of the fighting as well as any prospective peace talks.

The UN failure to stop the massacre of hundreds of thousands of Syrians has laid open the dysfunctionality of the global security architecture to help restore peace in intrastate conflicts with non-state groups involved – look to Libya, South Sudan or Yemen, to mention just a few. Furthermore, the inherent uncertainty surrounding the Trump administration will likely polarise the international community even further, making it even more sluggish to tackle the array of challenges that threatens the world.

Yet the UN will remain the world’s only institution capable of bringing the main combat actors of today’s conflicts to the table. As Carne Ross, a former British diplomat and founder of Independent Diplomat advisory group, put it, “the need for a brave and decisive new secretary-general is literally a matter of life and death. In fact, many deaths”.

- Javier Delgado-Rivera is a New York-based freelance journalist covering the United Nations and writing about the intersection between media and global affairs. His articles have been published in more than 15 international outlets, including Carnegie Council for Ethics in International Affairs, openDemocracy and UN Dispatch. You can follow him on Twitter @TheUNTimes

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Photo: UN Secretary-General-designate Antonio Guterres attends the ceremony for the appointment of the Secretary-General during the 70th session of the General Assembly on 13 October 2016 at the United Nations in New York (AFP)

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.