New world disorder: Trump's nationalist axis has upended global politics

Donald Trump appears to be single-handedly upending global politics. His appearance at a Helsinki press conference next to Vladimir Putin - saying things that might have made the Russian president blush if he weren't so poker-faced - was a clear sign of a world changed.

For traditionalist Cold War Americans, Trump's criticism of US intelligence agencies and almost deferential defence of Putin was an act of treason.

For those who view American power as one of the most destructive forces on the planet, it was a clear sign that the US empire is teetering.

As with much of what has happened since 2016, the Trump-Putin relationship raises questions about what kind of world order is emerging. This question applies to all regions, not least the Middle East.

As in the Syria conflict, Putin is often seen as challenging American strategic dominance. That picture is changing. Trump has moved closer to Putin over Syria, removing support for rebel groups previously backed by the CIA.

At the same time, Putin is moving closer to Trump's strongest ally, Israel's Benjamin Netanyahu.

The Russian president meets Netanyahu regularly; all three leaders share traits of nationalist ideology, in particular their opposition to globalist agendas and political Islam, a belief in military force, and the deployment of non-conventional forms of influence – from social media to the entanglement of business and politics.

Friends or enemies

Are there any real hard conflicts between major political camps - West and East - any more, or is everything we see a moveable war of position, in which switching sides is just part of the game?

It was Britain's then foreign secretary Lord Palmerston who famously said, at the height of the British empire in the 1840s, that there were no eternal allies and no perpetual enemies, only eternal and perpetual interests.

In our fast-changing multipolar world order, interests - political and economic - trump outdated alliances.

For example, right now Turkey’s President Recep Tayyip Erdogan and Israel's Netanyahu are calling each other fascists. Next year they may be buddies again. Three years ago, Russia and Turkey were enemies: now they are friends.

Has the United States, the world's most powerful nation, become just another rogue state - albeit one with the power to destroy the planet many times over? In a word: yes. Smashing up the Iran nuclear deal, backing Israel's brutal annexation policy and bullying allies at the UN are just some examples of why this is the case.

Since 1945 and the defeat of fascism, it was held that Western democracies were all part of one club and that their enemy was Soviet communism. That principle held until 1991, when the US ruled the world unchallenged following the fall of the Soviet Union, with Russia then inside the camp of "friendly nations," along with China and all the rest.

Following the 9/11 attacks, the US embarked on a new global war against terrorism that continues to this day. However, the changes that have occurred since the financial crash of 2008 and the Arab uprisings in 2011 are perhaps even more profound and have grown exponentially with the election of Donald Trump.

New nationalism

Fundamentally, the secure alliance of Western nations has begun to fray in the face of new political forces emerging in America, Europe and Asia. Since 2014 and the Russian annexation of Crimea, the West has moved into a new cold war with Moscow.

But rather than returning to the old familiar world of iron curtains and proxy wars, a new division is emerging, and it is emerging within the Western camp of "democratic" nations.

The most obvious factor in this new order is Trump. As a hard-right nationalist, he has broken with the globalist neoliberal consensus that has held for decades. He is seeking out alliances with like-minded nationalists, including Netanyahu and Putin.

Disenchantment with globalism and its institutions (the UN, EU, international law) is hardly unique to the US. It can be seen everywhere from the Brexit vote and its ardent champions in the UK Conservative party, to central Europe's nascent hardline nationalists, Italy's neofascist Deputy PM Matteo Salvini, and populists such as Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte and Colombia's Ivan Duque.

Their nationalism encompasses militarisation of policing and borders, violent outbursts against minorities, and war-on-terror rhetoric for problems as diverse as the drug trade and migration.

Ad hoc alliances

In a global capitalist order that is threatened by rising inequality, ungoverned spaces in which extremism can flourish and huge movements of people fleeing war and oppression, the nationalists have a common approach that unites them on major political questions. Because of this united dislike of international law and global agreements, they prefer ad hoc bilateral alliances that serve their political and economic interests.

This is Palmerston for the 21st century, with gunboats at the ready.

The new informal and emerging alliances have created huge problems for traditional conservative and liberal politicians whose political thinking is stuck in the old world. It presents great opportunities, however, for the other emergent political force: leftists in the West.

In Mexico, another silver-haired leftist, Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador, is president-in-waiting, with a thumping mandate.

Left challenge

Yet the West's new-old socialists have not always been very nimble-footed in identifying the novel aspects of the global nationalist wing of capitalism and seeing the opportunities that the growing divisions within capitalism present.

Modern politics doesn't fit into neat left-right lines. While at times the left will have to come to accommodations with the centre against the far right, the nationalists and the left may unite against the globalists on issues such as trade pacts. But at critical junctures, the nationalists and the centre will unite against the left to protect the status quo.

In Britain, the one thing that unites establishment liberals and nationalist Brexiteers is fear of the left coming to power with popular backing. Should that happen, 40 years of neoliberalism and untrammelled concentration of wealth and power will be threatened. And this threat is what leads to misinformation storms and distraction politics to undermine the left.

It is for this reason that Jeremy Corbyn has come under relentless attack from centrists in his own party and the mainstream media over alleged anti-semitism in the party. This attack comes from supporters of Israel and its colonialist hard-right regime, which has managed to create a narrative that protects it from criticism in Britain and Europe, while undermining the man who could make life difficult for it should he come to power.

This is why there is such a fierce attack on Corbyn now – in order to get the surrender in advance, and so tame him before he takes office

Indeed, if the left comes to power in Britain or the United States in the near future, it will look around the world and see few obvious allies. Instead it will come under immense pressure to reassure traditional partners that business as usual will continue, which means selling arms to the likes of Israel, Saudi Arabia, Egypt, and Turkey.

A Middle East dominated by Netanyahu and his Gulf allies, all engaged in maintaining occupation and denial of democracy and self-determination to peoples across the region, will not make life comfortable for any left government trying to support a world order based on peace and human rights.

This is why there is such a fierce attack on Corbyn now – in order to get the surrender in advance, and so tame him before he takes office.

New hegemon: China

And then there is China, the hegemon-in-waiting. In a world in which the old superpower has entered a period of dangerous senility, progressive parties could find common cause with China on issues of peace, climate change and trade.

China, as a post-revolutionary state with a rapidly advancing economy and strong global trade ties, could have more in common with leftist governments than the ugly crowd of nationalist leaders that are fomenting trouble in Europe, the Middle East and Washington.

As Western politics grapples with the rise of the global nationalist axis, the new left may well look east.

- Joe Gill has lived and worked as a journalist in Oman, London, Venezuela and the US, for newspapers including Financial Times, Brand Republic, Morning Star and Caracas Daily Journal. His Masters was in Politics of the World Economy at the London School of Economics. He is chief subeditor at Middle East Eye.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

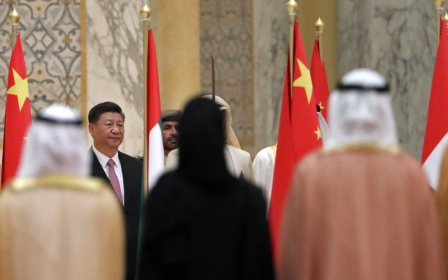

Photo: US President Donald Trump (L) and Russian President Vladimir Putin shake hands ahead of a meeting in Helsinki. (AFP)

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.