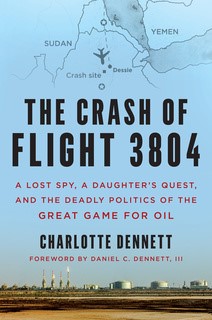

Oil wars and the unsolved death of America’s man in the Middle East

On 24 March 1947, a US C-47 military transport plane that was en route from Jeddah to Addis Ababa via Asmara crashed into mountains north of the Ethiopian capital, killing six Americans on board, including the US petroleum attache, and the Beirut-based cultural attache, Daniel Dennett.

Seventy years later, Daniel Dennett's daughter Charlotte is still trying to unravel the mystery of his death, and she has written a book about her long quest to understand the “great game of oil” that may have killed her father.

Daniel Dennett, a fluent Arabic speaker and scholar of Islam, also happened to be America’s top spy in the Middle East, working for the Central Intelligence Group, forerunner of the CIA. He’d come from a mission to observe US oil installations in Saudi Arabia and to help determine the route of the Trans Arabian Pipeline, which would eventually reach Lebanon. America’s overarching goal in the region, as he said in an official paper in 1944, was clear: “We must control the oil at all costs.”

Daniel Dennett's plane carried top-secret radio equipment and an aerial antenna, and would have enabled the US to carry out surveillance and communication across Ethiopia and the Near East.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

This was a critical moment in the "great game for oil" between the great powers - Britain was still the pre-eminent power in East Africa and the Middle East. America was the rising power, and already well placed in Saudi Arabia since its 1933 oil exploration agreement with King Ibn Saud.

Pipeline coup

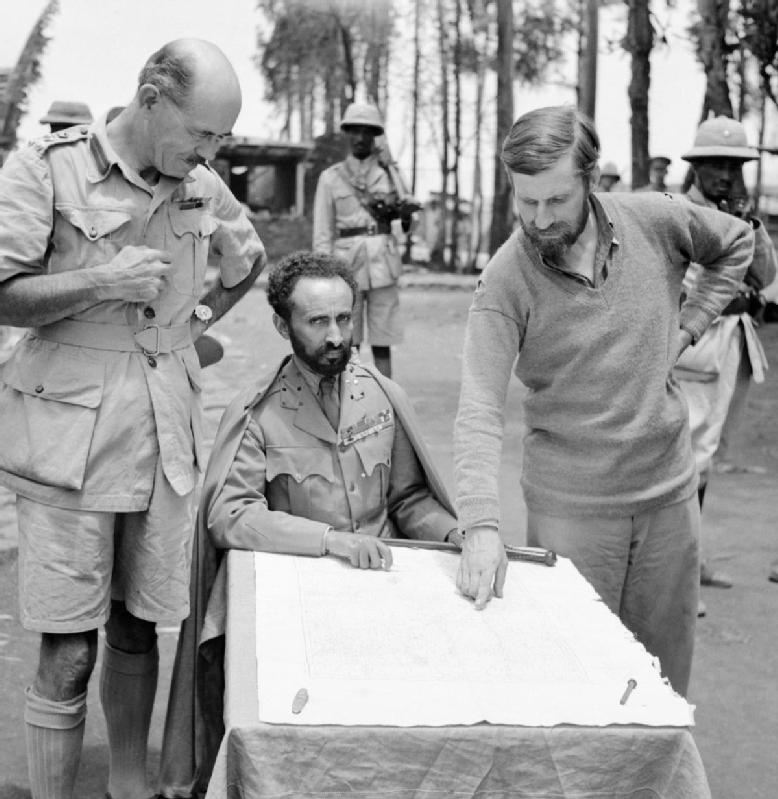

The US also wanted to edge the British out in Ethiopia, and Emperor Haile Selassie was open to the idea of removing the detested British with American help. This was a major strategic threat to British imperial and oil interests across the region. The British empire was still intact, despite the losses of World War Two, and London had no intention of surrendering its possessions and power to Washington.

Just before he took his fateful flight, Daniel Dennett - codename Carat - wrote to his wife from Saudi Arabia. “For reasons I will tell you later, I am going to Ethiopia,” he wrote. He would never return.

Aramco in those days was called the Arab American Oil Company. The proposed Trans Arabian Pipeline (TAP) was being held up: newly independent Syria was deeply reluctant to let it run across its territory, a route that would take it to the Mediterranean for loading onto tankers.

As Charlotte Dennett reminds us, the CIA carried out its first post-war coup in 1949 in Syria, a largely forgotten event (America’s coup list is so long), in which President Shukri al-Quwatli was replaced by a police chief who promptly approved the TAP route.

The pipeline was built and completed, but it was ill-fated: in the 1970s and 80s it fell victim to the Lebanese civil war and resistance to Israel and US imperialism (the pipeline ran through the Israeli-occupied Golan Heights).

Searching the archives

The author, now 73, was six weeks old when her father died. As a young reporter for the Daily Star in Beirut, she was shot at during the opening weeks of the Lebanese civil war in 1975, after which she got out of Beirut and returned to the US.

The Middle East connection in the family went back to her grandmother, who had been sent to teach biology at a Christian college for girls in Constantinople in 1900 (part of America’s soft power strategy in the Near East at the time).

In the 1990s, Charlotte Dennett began ploughing the US National Archives to read her father’s declassified reports, also returning to Lebanon and hanging out with former CIA spooks for nuggets of information.

A CIA officer who knew her father told her in 1995: 'We always thought it was sabotage, but we could never prove it.'

The burning question she wanted answered was whether the conclusion of the official report on the crash - that the plane had ploughed into the Ethiopian mountains due to bad weather - was true, or whether it was in fact sabotage, carried out by those who saw her father and the spy equipment he was transporting as a threat to vital strategic interests.

She had grounds for suspicion. A CIA officer who knew Daniel Dennett told her in 1995: “We always thought it was sabotage, but we could never prove it.”

The author’s self-confessed fascination with pipelines leads her down a path of research and analysis that sees oil and the pipelines that transport them as key to all the major Middle East wars and conflicts. This includes not just Iraq, but also Afghanistan, Israel-Palestine, Yemen, Turkey and Syria.

Iraq wars

There is little doubt that oil, and energy security, as it is often called, have played an important role in the planning of numerous western interventions in the Middle East over the last century.

The 1953 US-UK coup that overthrew Prime Minister Mohammad Mosaddegh in Iran followed his nationalisation of the British-controlled Anglo Persian Oil Company.

The 1991 Gulf war followed Saddam Hussein’s attack on Kuwait - the fear of Iraq controlling the oil fields that it shared with Kuwait (one of the emirates set up by Winston Churchill to secure British access to Arab oil) was a huge threat to western interests.

The author, in her quest for the truth of her father’s death and his role at the outset of the great game for oil, takes her central argument into many of the major regional conflicts, which she brings back to the same theme: controlling oil and its distribution.

Churchill and Balfour

The book traces how the great game for oil was set off before World War One, when Britain's first lord of the admiralty, Winston Churchill, ordered the British fleet’s primary fuel to be converted from coal to oil. While Britain had plentiful coal, it lacked oil. By 1917 the capture of Iraq to secure its oil fields had become a “first-class war aim”.

The author quotes then Foreign Secretary Arthur Balfour on the importance of oil for Britain. This was the same Balfour whose declaration of November 1917 gave a homeland to Jews in Palestine. His main Zionist interlocutor was Lord Rothschild, himself part of one of the most powerful oil dynasties in Europe.

The author explicitly links this infamous document to Britain’s overall strategy for securing Middle East oil. A century later, the state that Britain helped establish, Israel, has become a gas producer by exploiting fields off Gaza’s coast that are legitimately claimed by the Palestinians.

She speculates that US President Donald Trump’s “peace plan” for Israel, which reinforces Israel’s annexation of Palestinian territory, is in part an effort by his adviser and son-in-law Jared Kushner to revive the defunct Trans Arabian Pipeline.

Oil tycoons and double agents

For the author, a key suspect in the death of her father is British-Soviet double agent Kim Philby, who in the late 1940s was the head of British counterintelligence in the Middle East: he had been in Riyadh (where his father - an advisor to the Saudi king - was based) two months before Daniel Dennett’s death and for her is a prime suspect behind a possible plot to kill him.

The author drip-feeds her sleuthing on the 1947 crash in among her chapters on the various oil-linked conflicts of the Middle East. This can at times be a little distracting, as the story of her father and her discoveries about him is the driving thread and most compelling part of the book.

Her analysis of the great game for oil and its role in various conflicts is interesting, but at times there is a sense of her grappling with too much information, including news reports from recent events - which don’t necessarily provide the clarity required in a large-scale analysis.

There is a counter-argument to her thesis: that wars and interventions in the Middle East have multiple causes. To narrow it down to one, ie control of energy resources, inevitably risks simplifying something that is complex - geopolitics, national politics and energy can form a synthesis around decisions to go to war, or to intervene in another country’s internal politics.

But her aim is to point out that energy is never far from the publicly stated causes of western intervention in the Middle East (protecting civilians, WMDs, etc). “Those of us who have tried to decipher some of the complexities of the Middle East will inevitably bump into oil,” she tells MEE on Skype. “We have to be careful. It can’t account for everything. But it accounts for a lot.”

She says this truth has been obscured from the American public for decades. “There have been efforts over time to blot out that factor, and they have been very successful in the United States,” the author says.

War on terror, war for oil

A still relevant question is to what extent the war on terror since the 9/11 attacks is in large part a war to maintain US dominance of Middle East oil and gas resources. She quotes Frank Viviano in the New York Times writing weeks after 9/11: “The defence of these energy resources - rather than a simple confrontation between Islam and the West - will be the primary point of global conflict for decades to come.”

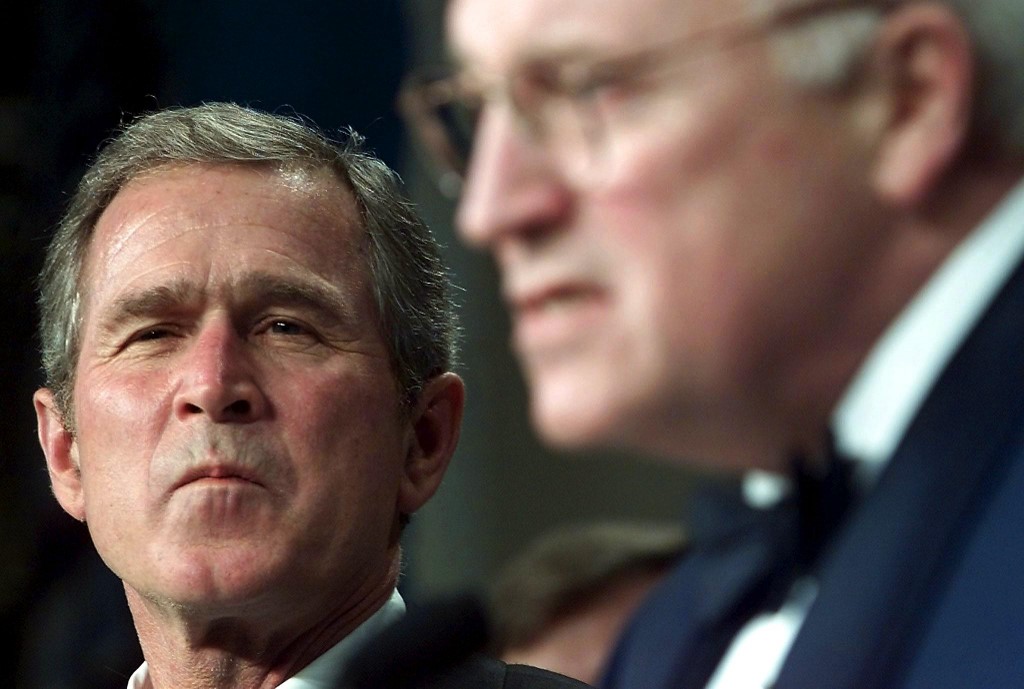

President George W Bush had an “oil cabinet” including Vice President Dick Cheney, an executive of Halliburton, whose oil interests extended from the Gulf to the Balkans. He had courted the Taliban in 1998 on visits to Afghanistan, as part of the new great game for Caspian Sea oil and gas, with Afghanistan as a possible pipeline route to Asia. Charlotte Dennett provides useful maps that elucidate the routes of pipelines and oil resources across the region.

There can be little doubt that oil was a decisive factor in the Iraq war of 2003. Bush aimed to remove Saddam Hussein, reassert US hegemony in the Middle East, secure US energy interests and open up Iraq to US and global contractors in what had been a largely closed market. The US taxpayer and Iraqi people would pick up the $1 trillion tab, while the no-bid contractors would reap billions.

In the wake of the invasion of Iraq, the country was opened up for western oil majors, who won contracts in a country that was previously a jewel in the western oil empire. Britain’s BP, which left the country in the 1970s, now pumps millions of barrels of oil out of Basra, while around it the people are in permanent revolt at abject conditions of corruption, joblessness and pollution.

Yemen war

Corporate profits, and competition for control of oil, gas and other resources, have played a galvanising role in the foreign policy of western powers for decades. In an interesting chapter on the Eastern Mediterranean race for gas, the author explores how Israel’s siege of Gaza and control of its waters, the war in Libya and Turkey’s tense relations with the US and Europe, are all linked to the battle over vast gas reserves lying under the Mediterranean.

Another undeclared energy war is Yemen. As the author shows, Yemen’s war has multiple causes but for Saudi Arabia and the UAE, control of key oil export routes, including the Mandab Strait, and also the coastal ports of the Mahrah governorate in south Yemen, are critical goals of their interventions. This is one of the main explanations for Saudi Arabia’s concentration of forces in the country’s south-east, a long way from the centre of fighting in the five-year war.

Hadhramaut province is also where Yemen’s oil fields are located and where a planned Saudi pipeline would reach Yemen’s southern port terminals.

Syria war

But there are caveats and counter-narratives. The author examines the question of whether the Syrian conflict was not a war against dictatorship and terrorism, as it is commonly portrayed, but a “pipeline war”. The argument was put some years ago by Robert F Kennedy junior, son of the senator killed in 1968 by Palestinian gunman Sirhan Sirhan.

Kennedy’s argument that Qatar had financed militant groups to try to overthrow Syria’s President Bashar al-Assad because of an aborted pipeline deal in 2009 has been widely discredited, by writers including Gareth Porter and MEE’s Paul Cochrane.

To her credit, Charlotte Dennett quotes Porter’s arguments that the main obstruction to Qatar’s plans was likely to be Saudi Arabia, not Syria. The conflict between the rival Gulf states was played out on the Syrian battlefield from 2012.

Covert western-backed action against Syria started under the George W Bush administration, in 2005, well before the alleged Qatari offer to Damascus in 2009 to build a pipeline through its territory to the Mediterranean.

What is undeniable is that Syria sits at the crossroads of major energy transport routes between Europe, Asia and the Arabian Gulf, and remains a strategically vital country. The author also explores the claim, widely accepted in Kurdish and Iranian discourse, that the Islamic State group was a western, Turkish and Gulf creation to destroy Syria and the Kurdish YPG federation.

Nearly 20 years after 9/11, President Trump reversed his decision to withdraw troops from Syria in October last year, announcing that thousands would remain to “protect” Syria’s oil fields in the country’s north-east.

Trump can always be relied upon to state baldly what other presidents would keep in the footnotes: that keeping energy resources in the Middle East under its or its allies’ control is always a major factor in policy, and considerably higher than any alleged concern over human rights and democracy.

CIA censorship

As her inquiries into her father’s death continued, Charlotte Dennett reveals layer upon layer of intrigue around the case. Three British-linked pro-Soviet “terrorists” - two Poles and an RAF pilot - had been in Ethiopia at the time of her father’s death. The report that weather was to blame was rejected in the first on-the-scene crash report by a US official, Colonel McNown (he was supposed himself to have been on the flight), who pointed out that none of the dead were wearing seatbelts.

The atmosphere at the time was tense, paranoid, with possible assassination and bomb plots signposted in frantic cables from US officials across the Near East, including "Carat".

In her dogged pursuit of documents that the CIA wanted to remain secret, the constant rejection of her FOIA requests eventually saw the author sue the agency in 2007. The case gained considerable press interest - and the attention of the CIA.

After the court backed the agency’s arguments of national security at the first hearing, her case was dismissed on appeal at New York City’s second circuit court on a technicality.

However, in the end, after decades of her efforts, the agency decided to embrace her and her family and belatedly recognise the importance of her father’s work in the Middle East, by naming a room after him at the CIA headquarters in Langley, Virginia.

In the final chapter we witness the commemorative event in May 2019 for her father - it came 70 years late, but at last recognised his service to the country, which made for an uneasy triumph for Charlotte Dennett and her siblings. Even CIA director Gina Haspel made a surprise appearance, telling the author, “keep at it”. “I don’t know exactly what she meant,” Charlotte Dennett tells MEE.

Back in 1942, Daniel Dennett had warned in a speech: “Pray to God that wherever else we may choose to intervene, the United States will be spared the disgrace of intervening in the Near East.” His words went unheeded.

The Crash of Flight 3804: A Lost Spy, a Daughter’s Quest and the Deadly Politics of the Great Game for Oil by Charlotte Dennett is published by Chelsea Green Publishing/Read Media

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.