The iconography of Palestinian martyrdom

Being killed by Israelis for the singular sin of seeking the liberation of their homeland has become a constant feature of Palestinian lives under the prolonged occupation of their ancestral homeland by a European settler-colony.

This very sentence, coming generations after other European colonial barbarities around the globe have ended, is a sheer fact of vulgarity beyond the reach of any reasonable prose. Even if Palestinians are not actively seeking liberation and are simply living their precarious lives - doing their duties as parents, teachers, nurses or journalists - they are still the victims of indiscriminate bombing or targeted assassinations by Israeli forces.

Icons such as a key, an olive tree or a keffiyeh have been identified as signposts of resisting the 'memoricide' of Palestinian history

Israelis maim and murder; Palestinians suffer and endure; the US and EU offer their sustained support for the murderers; Arab rulers look the other way; and the world remains aghast at the spectacle.

For decades at the mercy of organically pro-Israeli media in the US (where, on this issue, media outlets from Fox News to the New York Times are on the same page) or Europe (led by the BBC), Palestinian journalists are today a prime target of Israeli occupying forces. Palestinians are not allowed to tell their stories, even as professional journalists. They must be killed and silenced.

Today, western audiences can access the Palestinian truth (not “narrative”, as the common parlance falsely calls it) in plain English by professional Palestinian journalists, critical thinkers, historians and scholars around the world. This is what ails and troubles Israel. It has lost its monopoly on telling the world what happened. Palestinians are sharing the truth of Israel’s malicious acts of armed robbery against an entire nation.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

But what about the martyrs themselves - the men and women, young and old, who have given their lives and made the ultimate sacrifice for the liberation of their homeland? How are they remembered, and how does that remembrance impact the Palestinian cause?

Ethereal moment

Almost instantly after prominent Palestinian American journalist Shireen Abu Akleh was executed by Israeli forces last month, the iconography of her martyrdom surfaced in Gaza and other parts of Palestine. From posters and murals to digital renditions online, Abu Akleh secured her spot in the pantheon of Palestinian martyrology. But what do such iconic renditions ultimately signify?

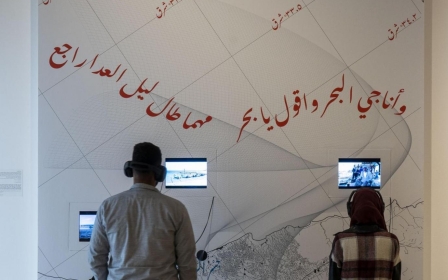

For decades, Palestinian and other scholars have studied such posters and murals from a variety of perspectives, building up a body of critical thinking. Icons such as a key, an olive tree or a keffiyeh have been identified as signposts of resisting the “memoricide” of Palestinian history.

A key aspect of this body of visual evidence is its post-secular nature; imagery that is decidedly iconic, but not in any denominational or sectarian sense. Some martyrs are Muslim, while others are Christian. Some, like the revolutionary icon Ghassan Kanafani, were devout Marxists. But their iconic remembrances are not in any such terms, as the iconography through which their heroic lives are celebrated has its own unique theophanic synergy.

In one mural that appeared in Gaza hours after Abu Akleh’s killing, a close-up portrait of her face is juxtaposed next to a helmet clearly marked with the word “press”, with a bullet piercing it and a second bullet in the air, on a trajectory towards her neck. To the left of Abu Akleh, another journalist is pictured mourning her loss, and over Abu Akleh’s shoulder is a panoramic view of Jerusalem, with the Dome of the Rock featured prominently. This iconography draws a parallel between the figure of Abu Akleh and the Dome of the Rock, signifying them as equally definitive to the Palestinian landscape.

The focal point of the mural is Abu Akleh’s smiling face and diverted gaze, frozen in an ethereal moment when she is both witness and martyr. It brings to mind the figure of Handala, the immortal witness whose face we never see, created by Palestinian artist Naji al-Ali.

The same type of iconography was evident when Palestinians remembered Razan al-Najjar, the Palestinian paramedic killed by Israeli forces during the 2018 Gaza border protests; Ibrahim Abu Thuraya, the Palestinian double amputee killed by the Israeli military in 2017 during protests over the US moving its embassy to Jerusalem; or Muhammad al-Durrah, the 12-year-old child killed by Israeli forces during the Second Intifada.

Palestinian civil religion

The names, numbers and iconic images are too many to cite. The question here is: How are their memories kept alive? The iconography reveals how decades of anti-colonial struggle in Palestine have crafted a collective consciousness that transcends religious denominations, sectarian politics or political ideologies.

Palestine has survived as a nation without a bona fide state, tyrannised by a state with an ideologically manufactured “nation”. Palestinians’ claim to their homeland is entirely factual and experiential, rooted in a history of struggle. This claim transcends all sectarian and denominational politics. The martyrology of Palestinian freedom fighters and professionals offers solid evidence of who has won and who has lost the moral and political battle for Palestine.

The historic formation of the Palestinian “civil religion”, as articulated by American sociologist Robert Bellah in the 1960s, is deeply rooted in their prolonged struggle against colonial domination. What the Zionist project has systematically failed to understand is that the more Zionists prolong their immoral, illegal and illogical theft of another people’s homeland by brute force, the more this very act of violent vulgarity produces the opposite of the intended effect.

The systematic articulation of a Palestinian civil religion is the highest expression of their multifaceted nationhood, which rises above and beyond anything a gang of settler-colonialists will ever achieve with their heavy weaponry, European diplomatic cover or US military arsenal.

The iconography of Palestinian national heroes and the allegorical stories they tell are not sectarian or denominational, belonging instead to a pantheon of a different liberation theology.

This iconography points to the formation of a civil religion that embraces all Palestinians, rooted in the lived experiences of a defiant nation refusing to submit to the military might of a Euro-American settler-colonial project. Its contours extend far beyond the borders of Palestine, offering fresh hope to a world torn asunder by both sectarian and secular fanaticism.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.