Prevent does not make us safer, but sows fear, suspicion and mistrust

Earlier this year, I was invited to give a presentation to a group of doctors, psychiatrists and medical practitioners. The brief was simple: "Can you tell us, how we are supposed to tackle radicalisation?"

As I spoke about the Prevent strategy, a doctor interrupted me halfway through and said, 'You have got to be joking.' I told him, that I was deeply serious.

The session was so popular that it was also delivered through a live feed to several different medical practices across the UK. As I spoke about the Prevent strategy, a doctor interrupted me halfway through and said: "You have got to be joking." I told him, that I was deeply serious.

Before I left, a consultant forensic psychiatrist told me that he was "very worried" about the consequences this could have on the doctor and patient relationship.

This comes after a BBC investigation published last week found that over the past year, the NHS have referred 420 patients and staff to police in England and Wales over concerns they were at risk of radicalisation.

At first glance, those statistics might send a shiver running down your spine.

READ: UK's Prevent strategy alienating Muslim communities, report warns

But pause for a moment and think about this: 415 children, aged 10 and under, have been referred to deradicalisation programmes in England and Wales over the last four years and almost 4,000 people have been referred to the deradicalisation scheme last year.

Those statistics do not come as a surprise to me: as an academic who has been researching the Prevent strategy since its inception, those numbers only give you half of the picture. The other half starts with the Prevent narrative. The story, as former prime minister Gordon Brown put it, starts with winning "hearts and minds".

Comply - or risk prison

The Prevent strategy aims to stop and prevent people from becoming terrorists or supporting terrorism. The Counter Terrorism and Security Act 2015 formally and legally expanded the job of tackling radicalisation and called for a partnership between the government, individuals and organisations.

Do I blame the individuals who have referred these individuals? No! The failure here lies with the strategy

And this partnership came with a new statutory duty for individuals and organisations in the public sector. That’s correct: a legal statutory duty which means if you fail to comply, you are at risk, in the worst case scenario, of imprisonment.

However, as the BBC's story revealed, this so-called partnership is increasingly strained because of peoples’ suspicions, fear and mistrust, and the way Prevent referrals are handled is problematic.

For example, anecdotal evidence has shown how some people are referred simply because they have started to wear a headscarf and in other cases because of their social media posts.

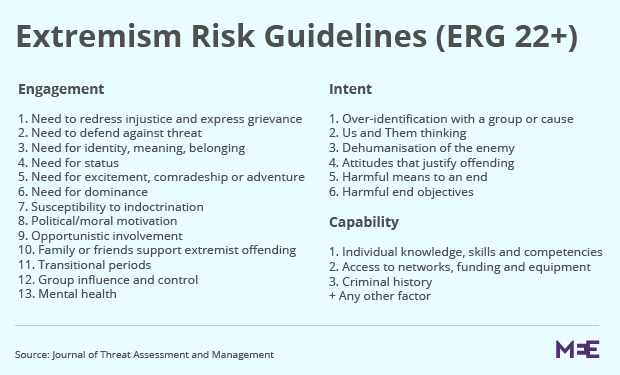

Do I blame the individuals who have referred these individuals? No. The failure here lies with the strategy and those compiling the list of 22 factors that a "Channel" panel would have to consider are people at risk.

Channel, the Prevent-linked counter-radicalisation programme, uses a collaborative approach between local authorities and statutory partners to help identify individuals who are at risk of being drawn into terrorism. The assessment comes through this list of 22 factors that can, according to the strategy, contribute to vulnerabilities around radicalisation.The list of behaviours include people who are changing their style of dress or personal appearance to align with a particular group, have lost interest in friends and activities or whose communications identify them as at risk of being radicalised.

Drop labels, do more research

A related problem with the strategy and the creation of a "suspect" community has been the blurring of the strategy’s main aims, which risks linking counter-terrorism with community cohesion and community development.

The 2011 strategy made the case for de-linking community cohesion and Prevent. However, there are always questions about whether the new Prevent strategy has been tangled into the web of cohesion policies.

READ: Home Office Prevent unit linked to Iraq 'black ops' PR firm

Historically, the Prevent policy has traditionally caused anger and resentment among many Muslim communities, and its impact upon British Muslims and the view that they have become the "new suspect" community should not be underestimated.

Given the problems that I've outlined, its clear that the government needs to develop a better understanding of how to prevent people from following a path of extremism that does not impact upon public institutions.

This requires a stronger research evidence base that can help improve understanding of the causes of terrorism. It also requires much more transparency and not the current secrecy around Prevent.

The Prevent strategy should do more to challenge and understand what makes someone become an extremist, and begin a process of engagement that can help remove the "suspect" community label that has been associated with the Muslim community. The problem with counter-terrorism policies, such as the Prevent strategy, concerns its potential to profile activities and people as extremists or terrorists without a robust evidence base.

Risk versus rights

A successful counter-terrorism strategy must ensure that it does not label everyone as potential targets because this will only further stigmatise and marginalise people.

As a society we should make clear that the golden thread that runs back to the Magna Carta is not broken by the current Prevent policy

As David Anderson QC, the independent reviewer of terrorism laws has stated, the strategy risks being a “significant source of grievance” and could be “ineffective or being applied in an insensitive or discriminatory manner”.

While terrorist attacks remain a concern, we should not give up our civil liberties for such protections. This type of Orwellian society will only lead to further unnecessary powers being given to the police and the state, whose scope is already too broad and intrusive.

We must also ensure that any such referrals under Prevent are not exercised for spurious reasons. And as a society we should make clear that the golden thread that runs back to the Magna Carta - justice, due process, and the principle of habeas corpus - is not broken by the current Prevent policy.

- Dr Imran Awan is an Associate Professor in Criminology and an expert on issues related to Islamophobia, cyber hate, policing, security and counter-terrorism. He is the author of a number of papers and books in this area and is editor of Islamophobia in Cyberspace: Hate Crimes Go Viral (2016).

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Photo: A man takes part in Friday prayers at the Baitul Futuh Mosque in Morden, south London on 20 November 2015 (AFP)

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.