9/11 attacks: Why the 'war on terror' has no clear ending

Towards the end of January 2002, I was having lunch with an Iranian friend in a restaurant in my hometown of Monterey, California. Our waitress overheard us speaking in Persian and asked: “Where are you guys from?”

I looked up at the waitress and replied in a proud voice: “I am from Iraq and he is from Iran.”

“Oh. All you need is a North Korean friend and you can have an Axis of Evil luncheon,” the waitress responded, apparently proud of her knowledge of global politics.

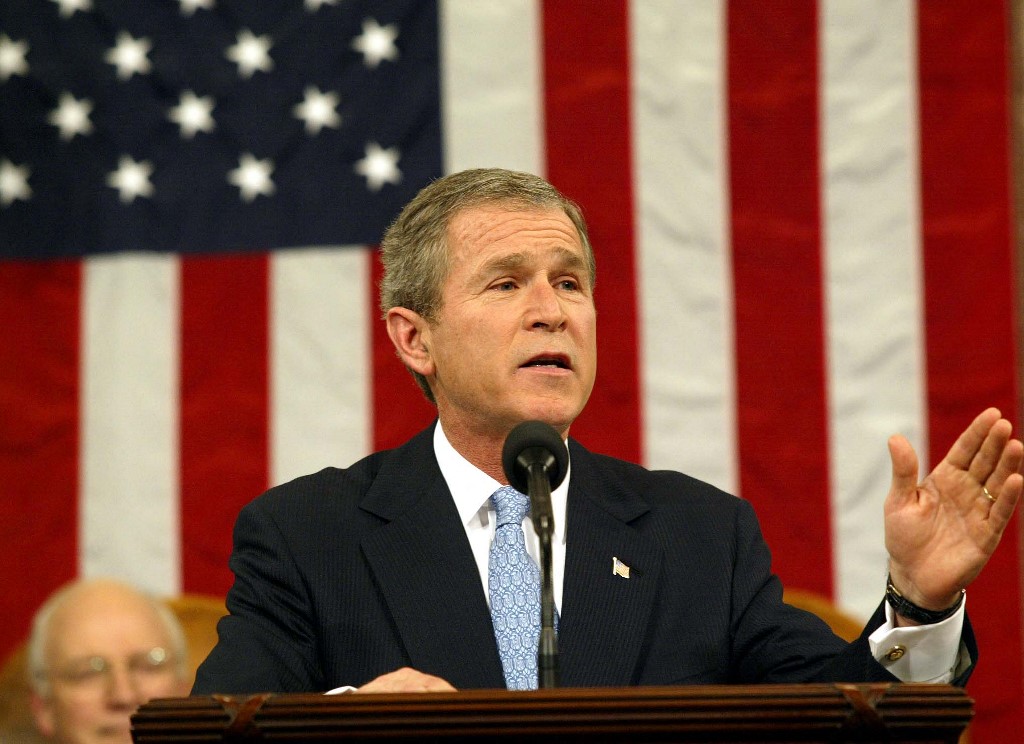

I think she expected us to laugh, or at least smile, at her clever quip - but neither of us was amused. The night before, then-President George W Bush had coined the term “Axis of Evil” in his State of the Union speech to refer to Iraq, Iran and North Korea.

Indeed, the 'Axis of Evil' justified 'Operation Iraqi Freedom' as a continuation of the 'war on terror'. A war against Iraq was justified by merely stringing together three three-word titles

I came to a few realisations after her comment. Firstly, I would give her only a 10 percent tip rather than the customary 15 in the US, and I would do so begrudgingly. Secondly, the US I had grown up in had changed for the worse after 9/11 for Muslims like myself. And thirdly, as much as I hated to admit it, these catchy titles worked.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Whichever speechwriter came up with Axis of Evil hoped to alienate the parties named, to set them apart from the rest of the “good” countries in the world. When the waitress grouped us into the unfavourable classification, I felt the marginalisation that the title was intended to inflict.

Not only did the title succeed in creating an identifiable enemy bloc, it also succeeded in working an entire political agenda into its listeners’ memories. After the speech, that waitress could still remember what the Axis of Evil was and who belonged to it.

Most US government initiatives, wars and villains can essentially be summarised in catchy two- to three-word titles: the “Cold War”, the “Red Scare”, the “New World Order”, the “Axis of Evil”, and finally the “war on terror”. The problem with these concise, catchy titles is that they repackage complex global phenomena into deceivingly simple components. They can also backfire; the war on terror suggests that only one of the two sides can win. In this case, it was Osama bin Laden.

Struggle for agency

Twenty years ago, when the neologism war on terror was coined, it implied that terror was something that could be targeted, fought and defeated. But in reality, terror was a worldwide problem that under-represented parties have resorted to for ages in their struggle for agency.

The Bush administration could have more aptly declared a “war on Osama bin Laden”, or even a “war on OBL” to fit into the three-word formula. Better yet, he could have launched a “war on al-Qaeda”. Yet, it was clear that such a broad name was intentional. There were those in the Bush administration who wanted to target not just al-Qaeda, but Iraq and Iran - and the war on terror gave them free rein to justify any military action in the name of seeking out terrorists, wherever they may be. Once the administration had created the villain of the Axis of Evil, it was compelled to act against it.

Indeed, the Axis of Evil justified “Operation Iraqi Freedom” as a continuation of the war on terror. A war against Iraq was justified by merely stringing together three three-word titles.

Samuel Huntington’s Clash of Civilizations, depicting an essentialist conflict between western and Islamic civilisations, was another easy three-word formula adopted by policymakers 20 years ago. What this theory neglected was the conflict wherein multiple Islams would fight each other for the loyalties of Muslims worldwide.

The conflict within Islam has been described in the West as a battle between “radical Islam” and “moderate Islam”, another problematic set of two-word titles. How does one measure whether a Muslim is “radical” or “moderate”? A Muslim is not a mobile phone with a battery symbol indicating the strength of his or her charge.

A better description for this dichotomy could be “nostalgic Islam” versus “dynamic Islam”. Those called fundamentalists and radicals have one unifying factor: they believe that Islam should be practised as it was during a mythical golden age. Some have deployed violence to destroy any country, entity or ideology that challenges their views.

When US troops entered Saudi Arabia in 1990 to eject Iraq from Kuwait, bin Laden feared the influence of Americanism on Saudi Arabia’s Islamic values, and hence eventually revived the group he founded in Afghanistan in the 1980s - what is known as al-Qaeda today.

Those Muslims who see Islam as fluid believe that their religion can evolve without losing its original nature practised during the prophet’s lifetime. They have managed to accommodate their beliefs within a modernising world. Yet, in doing so, they have also become the target of terrorist groups, the most violent of which, so far, has been Islamic State (IS).

Mythical power

After 9/11, al-Qaeda became the epitome of the new state of world affairs; a non-state actor capable of challenging the strongest power in a unipolar world. Bin Laden, as the man who the all-powerful US could not capture for a decade, had defied the odds - a feat that granted him an almost mythical power.

Al-Qaeda provided the model that new groups imitated. The exploits of bin Laden and his supporters sparked other disenchanted, nostalgic Muslims to act on its behalf, with other al-Qaeda groups emerging in the Arabian Peninsula, North Africa, Syria and Iraq, along with affiliates such as al-Shabab and Boko Haram.

The war against terrorism and the Iraq War that followed never achieved their goal of eradicating terror, but instead fuelled even more terrorist activity. The war on terror made bin Laden, a renegade, an adversary worthy of the attention of the world’s greatest superpower. It told a world of malcontents that one disgruntled man can orchestrate a series of events that can mobilise a superpower. It also provided a myriad of causes for those malcontents to rally against. Twenty years ago, bin Laden scored the ultimate victory.

We as Muslim Americans, on the other hand, were the losers in this conflict. For two decades, we have been subject to discrimination as a result of this open-ended war. German or Japanese Americans endured systemic prejudices, but World War Two had a clear ending. Even with the death of bin Laden, anti-Muslim discrimination persisted with the rise of IS.

For us, there was no Berlin or Tokyo to surrender and declare that the war was over. Perhaps it will take the fall of Kabul, an American surrender, to finally signal the end of this latest “three-word” war.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.