Vogue and female empowerment: The 'glam-washing’ of counter-extremism

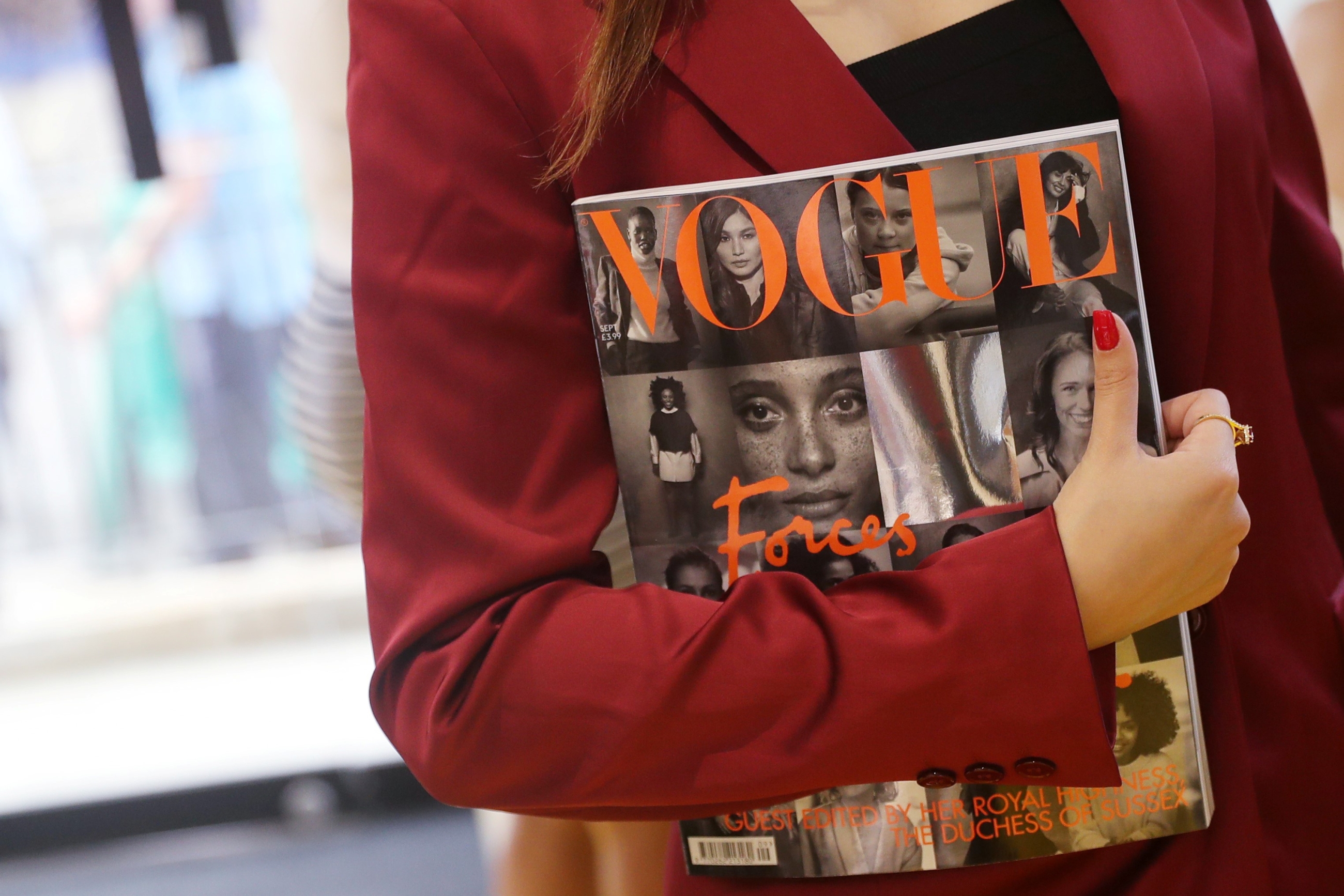

Vogue magazine is famed for its pursuit of luxury, runway models, celebrity endorsement and generally lending its column inches to all things vanity.

So it came to my surprise when I stumbled across an article online at British Vogue with the headline “The Women At The Forefront Of The Fight Against Extremism” written by journalist Giles Hattersley on 12 October.

The counter-extremism industry

The article focuses on three women working in counter-extremism domestically and abroad: Yasmin Green of Jigsaw, Nikita Malik of the Henry Jackson Society and Sara Khan, the commissioner for countering extremism. The author outlines that these women are "not spies, nor running intelligence services” but are simply “keeping us safe today”.

The more I read the article, the more it felt like an advert for the organisations these women work for as well as an endorsement of the wider counter-extremism industry

The more I read the article, the more it felt like an advert for the organisations these women work for as well as an endorsement of the wider counter-extremism industry.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

This article was well-timed, considering Sara Khan’s report on “Hateful Extremism” was published last week, triggering debates on Twitter about what constitutes "extremism" and the effectiveness of the Prevent Duty, the UK’s counter-extremism policy.

There are two fundamental issues with the article that draw my attention. Firstly, the way that the counter-extremism industry is glamorised (in a fashion magazine no less) with no mention of the well-documented harms such extensive surveillance practices have caused.

Stigmatising Muslims

Since their inception after 9/11, counter-extremism measures have routinely and predominately stigmatised Muslim communities worldwide. Although counter-extremism professionals claim that the focus is on "everyone", the very creation of these policies stemmed from a problematisation of Muslim communities, which continues to the present day.

Whether it was through the use of undercover informants gathering intelligence in US mosques and Muslim student groups or the installation of CCTV cameras in Muslim areas in Birmingham, the intimate connections between counter-extremism and counterterrorism has a long and complex history.

But the article failed to mention these points, instead choosing to erase the experiences of those impacted by the very policies Green, Malik and Khan promote in their field of work. Should we ignore, for example, how Muslim practices and beliefs are sensationalised as potentially extreme in Prevent Duty training?

There is a glaring oversight in the article on how counter-extremism policies specifically impact Muslim women

Or the fact that a 13-year-old Muslim boy was questioned suspiciously because he used the word "eco-terrorist" in a French lesson?

This erasure itself is harmful, as it allows for the continuation of these policies and measures without its deserved scrutiny, thus rendering counter-extremism as a normalised and necessary part of society.

Doing what Vogue does best, the article bedazzles its readers with high-end aesthetics and portrait figures of these counter-extremism practitioners in an attempt to divert our attention from its miserable realities.

The second issue is the way that women - and Muslim women especially - are routinely depicted as "saviours" in counter-extremism discourse. Although it is Muslim males who are more likely to be referred onto programmes like Prevent, it is Muslim women - mothers specifically - who are routinely asked to pick up the pieces by the state.

The Vogue article was written to celebrate the achievements of these women, who "against all odds" are succeeding in their roles. Take for example Sara Khan, who in the article “thumps the table cheerfully” before saying “I’m just going to get on with it”, when talking about the protests she faced because of her appointment as commissioner for countering extremism.

Securitisation of motherhood

The article asks whether having “a Muslim woman in high office would generally be considered a good thing” as if it is some kind of success that such oppressive practices are carried out by those who apparently resemble us.

Women are encouraged to “challenge extremism” because as the “backbone”, they “can see if their children are being radicalised”.

There is a glaring oversight in the article on how counter-extremism policies specifically impact Muslim women

Firstly, such a suggestion relies on the assumption that women are more inclined to "fight" extremism simply because they may be mothers. Not only is this incorrect, but it will inevitably result in the securitisation of motherhood as an expectation is placed on mothers to inspect and monitor their children and homes carefully.

This is not empowering as it instead puts responsibility and ultimately blame onto them should they fail to carry out these duties. There is a glaring oversight in the article on how counter-extremism policies specifically impact Muslim women.

As my research on the Prevent Duty in schools has found, Muslim mothers in particular are expected to navigate the hostile bureaucratic Prevent structures if and when their children are referred.

Counter-extremism measures routinely use Muslim women in their campaigns, as seen a few months ago, when it was revealed that the Home Office was covertly sponsoring content for the SuperSisters platform, designed for British Muslim teenage girls.

'Glam-washing' counter-extremism

Rather than improve the socio-economic positions of Muslim women, who are at the receiving end of both Islamophobia and sexism in the workplace, the use of Muslim women becomes limited to securitising policies.

I also cannot separate the way that Shamima Begum was treated, following her pleas to bring her baby back to the UK so that they had a chance of survival. Her requests were turned down and not only was her citizenship revoked, but her baby also died. Was she not a mother too?

This was not the first time that Vogue had commissioned a piece on counter-extremism workers. Nor was it the first time that the magazine has been criticised for their choice of interviewees. The net result of this article however will no doubt be the introduction and embellishment of provocative and highly criticised counter-terrorism practices to an unassuming new audience.

The use of fancy aesthetics and sleek outfits cannot conceal the realities of counter-extremism, and we must refuse attempts to "glam-wash" such campaigns in the name of "empowerment".

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.