Turkish elections: Where has Erdogan's 'economic miracle' gone?

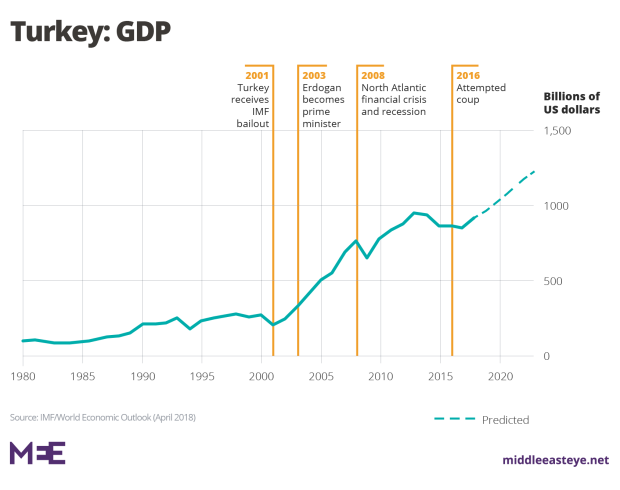

When Recep Tayyip Erdogan's Justice and Development Party (AKP) swept into power in elections in 2002, Turkey had just received the first part of what would eventually be a $20bn International Monetary Fund bailout.

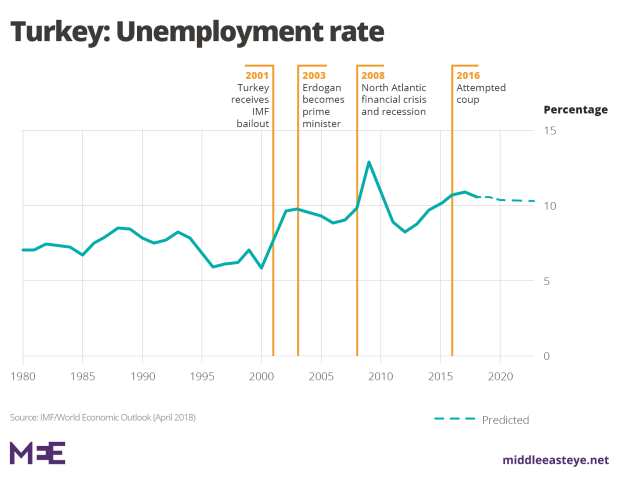

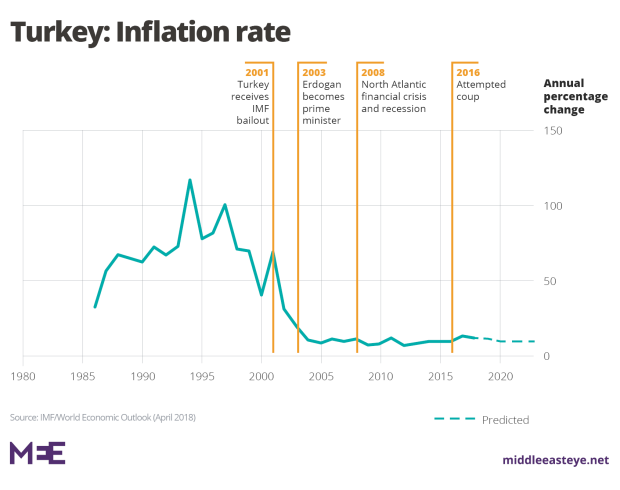

Decades of secular rule, when governments perceived as threats to the secularism and stability of the republic were periodically removed by the military, resulted in regular destructive bouts of inflation, high interest rates and slow growth.

Erdogan was initially not given much of a chance by the army and his secular opponents. They assumed the AKP would be banned, as other Islamist parties had been in the past, and that they would soon resume political control.

But Erdogan understood the importance of infrastructure better than his rivals. As mayor of Istanbul in the 1990s he had already demonstrated this by cleaning up the city, laying sewage and water pipes and building more roads and bridges.

Scepticism about Erdogan's rule gave way to what was widely described as an "economic miracle" that was inclusive and brought in the forgotten religious conservative Anatolian hinterland that was the AKP's political bedrock.

On Thursday, Erdogan made the first landing at a new international airport in Istanbul that is still under construction and scheduled to open in October, showcasing what is expected to become one of the world's biggest transport hubs.

For years as prime minister, Erdogan ran the country for the benefit of most Turks, and not as the cartoon demagogue that he has been painted as by some at home and abroad. Although, since the coup attempt of July 2016, things have changed.

A run on the lira over the past 18 months has brought back some rotten memories of the currency's travails under previous governments, for which, the usual suspects - international investors and “foreign agents” - have taken the flak.

Hot money a concern

But hot money has always been a concern in Turkey. The economic miracle could not last forever and something had to give eventually.

The first to move money are usually politically connected individuals, closely followed by local businesses. Stocks and bonds are always – though not exclusively - the last. Problems always ripple out. They only need a trigger to magnify them.

In this case, it was Erdogan's insistence that he'll be more hands-on with the central bank, and his claim that interest rates cause inflation, which went down spectacularly badly with investment fund managers and bankers who met the Turkish president during his visit to London last month.

Is the economy too hot? A growth rate of 7.4 percent, inflation at more than 11 percent and a currency that has tanked certainly suggest something is out of kilter.

Now the economy is double the size it was a decade ago.

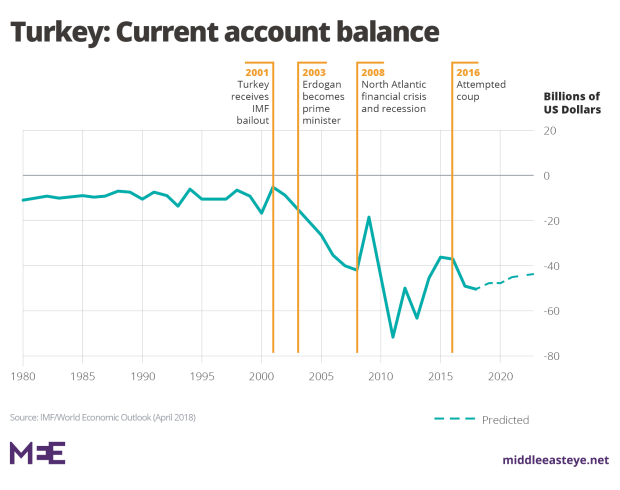

But there are warning signs. Some companies are borrowing too much money from overseas. The country is sucking in too many imports, and money has to be found from somewhere to pay for them.

The IMF and many economists believe the economy should be ticking over at a pace of four to 5.5 percent a year, a rate the IMF in its latest report on Turkey considered to be "more in line with the potential of the economy".

But cheap loans and an over-reliance on construction mean the economy has overreached that potential.

Traditional view of usury

Erdogan had always surrounded himself with well-regarded political partners, such as Ali Babacan, the former deputy prime minister with responsibility for the economy.

But since the failed coup they seem to have been replaced by ideologues. Who now is challenging Erdogan's assertion that interest rates cause inflation?

But he should be railing against inflation and not picking fights with credit rating agencies and investing nations.

And here’s the crux. Economies rise and fall. Erdogan could have gracefully transitioned into Turkey's traditionally ceremonial presidential role, playing the elder statesman and leaving politics to a younger generation.

But polls ahead of Sunday's elections suggest he retains enough popular support to remain in office. And a new system of government that concentrates political power in the office of the presidency – introduced via referendum last year - will only consolidate Erdogan's dominant influence.

Beijing, for instance, encourages investment in education and research and development, despite periodic crackdowns on political dissent.

What Turkey has proved under Erdogan is that it can build cars and washing machines as cheaply as the next developing nation. But it hasn’t incentivised or spent enough on the next stage of development - hi-tech industries. You can’t rely on shopping malls forever.

- Abid Ali is a freelance business and economics journalist. He has more than two decades of experience working for Bloomberg, CNBC and CNN. He was the business and economics editor for Al Jazeera English for more than seven years.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Photo: Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, photographed at the opening of the Bosphorus tunnel in December 2016 (AFP)

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.