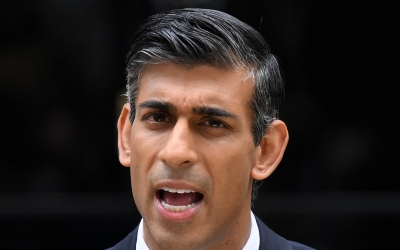

Rishi Sunak might 'look like us', but he is loyal to his class

Britain last week welcomed a new prime minister, not elected by the people. Yes, you read that right: a select few from the Conservative Party lent their backing to Rishi Sunak, constituting enough support to replace Liz Truss.

Yet, the general public’s attention was not so much on a new Tory leader who the people did not elect, but on the background of the new prime minister. This is, allegedly, a historic moment being compared to former US President Barack Obama’s win - although he won via the mandate of the people, not a select few.

The events of the past few days should force us to ask some urgent questions. How is representational politics, based solely on sharing the same heritage as someone, a helpful measure of political consciousness? What does it mean for economically marginalised citizens to have the wealthiest MP as our prime minister? It has been duly pointed out that Sunak is richer than King Charles III, with an estimated fortune of £730m ($845m).

Sunak as the grateful immigrant who remains deferential to the metropole of empire is the only way to secure the insecure

Indeed, this moment will not necessarily entail any form of tangible economic change to help those in dire need during a massive and widespread cost-of-living crisis. This momentary lapse of asserting that we are in a post-colonial, post-racial world is little more than denial, exposing how racecraft is understood through acquiring higher positions of power. It shifts the focus away from political deceit, deepening inequalities and social breakdown that will take decades to rebuild.

Sunak, in this sense, represents his class - those at the very top. Class is a variable that stratifies Britain in a multitude of ways; a form of social engineering that none of us can escape. His presence as the country’s leader is what I would call a mythic racial nightmare.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

The merging of economics with race here is an acute way of emphasising how the leader’s aesthetics mark a cosmetic change, while the same fiscal policies are retained, benefiting those in the same economic position as Sunak. Just this year, Sunak gave a speech in Tunbridge Wells where he boasted of diverting public funds from “deprived urban areas” to more affluent constituencies.

Easing white anxiety

Sunak is committed to the Rwanda plan, wherein refugees arriving on the shores of Britain are deported to Rwanda to have their paperwork processed. He has also expressed his desire to widen the definition of extremism, targeting those who “vilify Britain”.

This is an intriguing point. A day before Sunak accepted his premiership following a meeting with the king, he articulated how he wanted to give back to the country to which he owed so much. He thus not only declared himself the leader of the country, but also asserted that he is not a danger, emphasising his utmost loyalty. Such a public admission exculpates him of being the “Other” and eases white anxiety.

Sunak as the grateful immigrant who remains deferential to the metropole of empire is the only way to reassure the insecure, affirming the notion that Britain cannot possibly be racist. The making of the servile sahib with access to the head of the table is not an unknown tactic.

Amid Britain’s colonisation of India, the famous “Minute on Education” speech was delivered by Thomas Macaulay in 1835. He shared his ambitions on how to advance the British empire, noting: “We must at present do our best to form a class who may be interpreters between us and the millions whom we govern - a class of persons Indian in blood and colour, but English in tastes, in opinions, in morals and in intellect.”

Expansion of capital

I would propose that things are no different today, albeit without the British Raj. A similar machine is at play: the expansion of capital within the upper echelons of society, with the crumbs littered among those at the bottom, the working class.

Sunak’s ascension has been hailed as an advance for other South Asians in Britain, despite their immensely different experiences. Unlike the vast majority of South Asians in the UK, Sunak’s personal migration story is often referred to as one of the “twice migrants”. Originally from Gujranwala (in today’s Punjab in Pakistan), his family moved to Kenya before migrating to the UK in the 1960s.

The belief that most South Asians in Britain, who are working class, will somehow feel elated at seeing someone who “looks like them” in power - that this should be sufficient to reduce their economic anxieties - amounts to a subtraction of race from economics. This is what I call abject politics: a politics incapable of critiquing state actors, because representational politics is weaponised as a distraction.

The South Asians who had already settled in Britain before the arrival of East African Asians forged politically radical movements that fought vehemently against assimilationism and encouraged pushback against those in power.

A momentary romanticism of “being seen” will not save us from the cost-of-living crisis. Indulging this moment obscures and erases the damage that the Conservative Party has done to the country for 12 years.

Now is the time to build collectively from the ground up. It is time to smash the egregious policies passed by government actors and stop masking the violence of those in power simply because they “look like us”.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.