US aid to Egypt: Wrong but inevitable

“The human hand that grants wheat knows how to sharpen the weapon,” wrote the Egyptian poet Amal Donqol. His words perfectly express the aid that the US gives to Egypt.

Since 1948, the US has provided Egypt with $77.4bn in foreign aid

Since 1987, the US has provided $1.3bn in military aid annually to Egypt to enhance its longstanding cooperation - diplomatic words for “leverage” with the Egyptian military who dominate the country’s political scene.

After a two-year suspension as a result of Abdel Fattah al-Sisi’s worsening human rights record, it was resumed in 2015 ostensibly to help Sisi fight the Islamic State in his country.

Instead, as Sisi has failed to contain the militant group, that money – as experts testified last month at a congressional hearing - has become a total embarrassment for Washington.

“The primary priority of the Egyptian military and general Sisi is not to fight terrorism or improve governance,” Tom Malinowski, assistant secretary of state for democracy, human rights and labour from 2014 to 2017 said at the Senate hearing on 25 April.

“It has been to make sure that what happened in 2011 in the Tahrir square uprising can never ever, ever, ever happen again.”

The Trump administration, like Sisi, is less interested in countering IS than in continuing its relationship with the Egyptian military

Yet despite the unanimous recommendations from speakers at the hearing that the US should completely rethink its aid to Egypt, it is highly unlikely that Washington will scale it back.

That’s because the Trump administration, like Sisi, is less interested in countering IS than in continuing its relationship with the Egyptian military.

In other words, the US’s strategic interests are more important by far than those of Egyptians seeking democracy.

Securing dependency

Take the Suez Canal which the Egyptian military essentially controls.

Not only does 8 percent of all global maritime shipping pass through here annually, but Egyptian officials regularly expedite the passage of dozens US naval vessels, a clear benefit for US forces deploying to time-sensitive operations in the Mediterranean, the Persian Gulf or Indian Ocean.

Keeping the Egyptian military dependent on US defence contractors gives Washington leverage over policy-making circles in Egypt. Although, of course, in reality this only works when there are strongmen like Sisi, with a military background, who has the requisite power in his hands to negotiate in a way beneficial to the US.

Deals made only in US interests

If Egypt was ruled by democratic institutions, the US could say goodbye to its foothold. Instead, the leverage that the US has a result of its aid crushes the hopes of Egyptians for civil society to flourish. When push comes to shove, US interests always seem to contradict America’s proclaimed democratisation agenda in the region. The interests always win.

For instance, it took just one meeting last month between Sisi and Trump to pressure the Egyptian president to release Aya Hijazi, the dual US-Egyptian citizen, along with her husband and six other Egyptians.

Back in 2012, when Egypt was ruled during a transition period by the SCAF (military junta), police raided several NGOs and arrested 43 workers, including Americans, Europeans and Egyptians. They were referred to a criminal court over charges of espionage and fomenting unrest in the country

If Egypt was ruled by democratic institutions, the US could say goodbye to its foothold

A few days later, the Egyptians were the only defendants who still stood for trial after a court lifted a travel ban on the foreigners, including seven Americans who had to pay $300,000 bail each.

Like Hijazi, the following day, seven Americans and other foreigners were flown by a US private air charter to Cyprus and then back home as the Egyptian parliament and media attacked the government for succumbing to US pressure and allowing them to leave during court proceedings.

The foreign defendants were later sentenced in absentia. Several Egyptians who were lucky and found a way to leave the country, applied for asylum in the United States, such as Nancy Okail and Sherif Mansour. But the others ended up as scapegoats in jail with no government applying pressure for their release.

Not about peace

Contrary to popular belief, Washington does not give aid to Egypt to ensure that Egyptian government maintains its peace deal with Israel.

This might have been the case during the time of Anwar Sadat who signed the Camp David accords in 1978. But as time has passed, maintaining peace with Israel has become of greater interest to Egypt than the US.

After all, the US gives the Israeli military three times more aid - $38bn over the next decade to be precise - than Egypt to ensure the country’s military superiority over its neighbours.

►READ MORE: The $38 billion dollar deal that will do very little

But in Washington, no one is debating whether Israel, despite historical massacres and ongoing violations committed against Palestinians, deserves its aid.

In fact, neither Egypt nor Israel really need this massive funding. The regional balance of power could be maintained by much less. But then what would fuel the US arms industry or feed the endlessly hungry arms race in the region?

Into the arms of France and Russia

In the aftermath of the violent dispersal in 2013 of pro-Morsi protest camp in Rabaa Square, the Obama administration suspended military aid to Egypt for the first time in decades. US law prohibits assistance to a government whose elected leader is deposed by a military coup.

But realising how much the US had lost as a result, in March 2015, his administration resumed the aid programme – but critically, it had reformulated its framework.

In a separate National Security Council press release, NSC spokesperson Bernadette Meehan noted that the Obama administration had also decided to end Egypt’s use of cash flow financing (CFF) – the financial mechanism that has enabled Egypt to purchase equipment on credit – in 2018.

“By ending CFF, we will have more flexibility to, in coordination with Egypt, tailor our military assistance as conditions and needs on the ground change," the press release said.

Obama’s changes to the aid - which Egyptians had taken for granted for decades as a reward for the peace treaty with Israel - pushed Sisi to seek other partners who could enable large-scale equipment procurement on credit. He found them in France and Russia – and without any of the Obama administration's human rights obligations.

In 2014, France sold Egypt four naval frigates in a deal worth $1.35bn. In the autumn of 2015, France announced that it would sell Egypt two Mistral-class helicopter carriers (each carrier can carry 16 helicopters, four landing craft, and 13 tanks) for $1bn.

It's possible that the $23bn that Saudi Arabia, Kuwait and the UAE granted to Egypt to keep its economy afloat was used to buy this equipment

In a separate deal with Russia, Egypt will purchase 46 Ka-52 Alligator helicopters which can operate on the Mistral-class helicopter carrier. Other Russian-Egyptian arms sales include Antey-2500 (S-300) anti-ballistic missile system ($1bn contract) and 46 MiG-29 multirole fighters ($2bn contract).

In the absence of accountability and transparency, it’s possible that the $23bn that Saudi Arabia, Kuwait and the UAE granted to Egypt to keep its economy afloat starting in 2013 after Morsi was ousted was used to buy this equipment - even as Egyptians felt the pinch of double-digit inflation and unemployment.

Billions of what ifs

Despite these deals, Egypt cannot do without US equipment such as F-16 fighter jets, Harpoon missiles or 125 M1A1 tanks. Likewise, the US doesn’t want Egypt to resort to its historical foe, Russia, especially given Putin’s expansionist aspirations in the region.

If the majority of US aid had gone towards developmental projects, would Egypt still need US assistance today?

So these mutual desires have helped kick the can of differences down the road, especially with the rise of Trump.

Since the era of Nasser, Egypt has been stable enough, teetering along until the 2011 uprising broke out. But this stability came at the expense of democracy and economic progress, leading to the deterioration of all aspects of life that now haunt Egyptians.

Since 1948, the US has provided Egypt with $77.4bn in foreign aid. One can’t help but wonder if the majority of this funding had gone towards developmental projects, such as improving education, health and scientific research, whether Egypt would be in a different situation today, one in which US assistance would no longer be needed.

- Muhammad Mansour is an Egyptian journalist, who covered the Arab uprisings, and writes about Egyptian affairs, the Sinai insurgency and broader Middle Eastern issues. For more details, visit www.muhammadmansour.com.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye

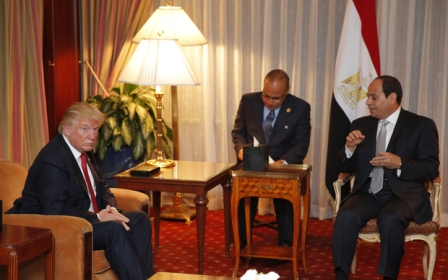

Photo: US President Donald Trump listens while Egypt's President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi makes a statement to the press in the Oval Office before a meeting at the White House on 3 April 2017 in Washington, DC (AFP)

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.