Guantanamo: Why Biden, just like Trump, cannot close this brutal prison

“For the last two decades, the most notorious prison in America has been Guantanamo. We know it today. And we knew it when the Senate judiciary committee held its first hearing on closing the detention centre at Guantanamo in 2013.”

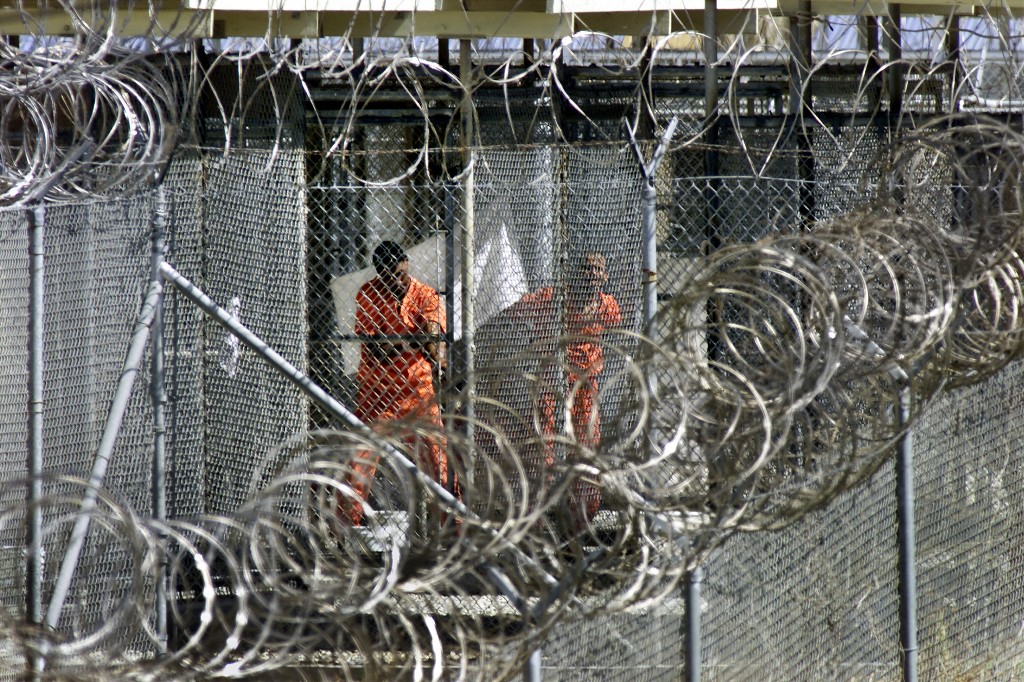

These words were delivered by Senator Dick Durbin during the opening statement of a hearing by the committee on 7 December. Though the intention of the hearing was clearly signalled by its title - “Closing Guantanamo: Ending 20 Years of Injustice” - conclusions remain elusive. Exactly 20 years after the infamous prison was opened to house prisoners of America’s “war on terror”, there is still no end in sight.

Durbin, one of the most outspoken legislative advocates for closing Guantanamo, argued during the December hearing that keeping the prison open was costly, that it impacted the US’s reputation and that it threatened US national security.

The oft-repeated narrative that Guantanamo serves as a 'terrorist recruitment tool' deflects away from the US’s violent legacy of torture

In a similar vein, one of the military witnesses at the hearing, retired Marine Major General Michael Lehnert, asked: “Who gains by keeping Guantanamo open? Not America. Those who would harm us are the ones who gain. They point to the existence of Guantanamo as proof that America is not a nation of laws. They use Guantanamo as a recruiting tool. They do not want us to close Guantanamo.”

Just over a month before the hearing, former Guantanamo detainee and torture survivor Majid Khan testified directly about his experience in CIA custody. Khan’s testimony was the first of its kind and it prompted widespread condemnation of his treatment, including by the panel of military jurors overseeing his sentencing.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Despite this opportunity to open a dialogue about how to meaningfully address the legacy of torture and brutality at Guantanamo, Durbin's was the only voice to directly acknowledge it, adding that “this abuse was of no practical value in terms of intelligence, if any other tangible benefit to US interests”.

US's violent legacy

However, it is wrong to torture, whether or not useful information is gained. By glossing over the brutality Muslim prisoners have been subjected to as a fundamental reason for closing Guantanamo, even staunch critics of the prison legitimise the dehumanisation of Muslims that justified building it in the first place. And the oft-repeated narrative that Guantanamo serves as a “terrorist recruitment tool”, especially, deflects away from the US’s violent legacy of torture and indefinite detention that has made the prison infamous.

Twenty years and three prior presidential administrations since Guantanamo Bay prison opened under the guise of the war on terror, its closure now rests in President Joe Biden’s hands. Although the Biden administration has signalled its intention is to close Guantanamo, its actions thus far indicate that they are not prepared to expend political capital to see this goal through.

Not only did the administration fail to send a representative to Senator Durbin’s hearing, but the president has also signed the 2022 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA), despite it retaining decade-old restrictions on the use of federal funds for prisoner transfer from Guantanamo that effectively prevent the release of detainees even after they have been cleared through both legal and national security processes.

Although Biden criticised the NDAA’s Guantanamo provisions in a concurrent statement, his fundamental inaction is symptomatic of how real progress toward closing Guantanamo and reckoning with its brutal legacy is stymied by deep undercurrents of American Islamophobia. These undercurrents influence the debate on both sides in the form of anti-Muslim narratives as well as the erasure of the victims and survivors.

Tellingly, during the two-hour-plus long Senate hearing on the closure of Guantanamo, the prisoners’ Muslim identity was only mentioned once. The logic of collective responsibility and punishment - applied uniquely to Muslims in the context of the war on terror - however, formed the backdrop throughout.

Supposed risk of release

One way in which the Islamophobic fallacy of collective responsibility is perpetuated is the insistence that the remaining detainees can not be safely released because of the supposed risk of recidivism.

There are numerous problems in how recidivism rates are calculated, including the wide scope of what is considered reengagement which, according to Guantanamo defence lawyer Michel Paradis, includes any interviews, books and speeches that criticise the US. Moreover, data do not support the assumption that recidivism is more of a problem in the context of the prison than it is in the rest of the criminal justice system.

Finally, recidivism is an incorrect term to describe future violence perpetrated by a detainee who was never actually charged with a crime. The most troubling aspect of this argument, however, is how it asserts that Guantanamo prisoners can be held essentially as proxies for others who have resorted to violence. That prisoners can be held for the crimes, real or imagined, of others rather than their own epitomises the rationale of collective responsibility for Muslims that permeates discourse in the war on terror.

Contributing further to the perpetuation of the narrative of collective responsibility regarding Muslim detention at Guantanamo is the US’s recent military withdrawal from Afghanistan. Rather than sticking to the government’s claim that the war in Afghanistan is now over, suggesting many of the detentions should also end, the aftermath of chaos and violence that the US left behind in that country has been leveraged as yet another reason why Guantanamo should not be closed.

That prisoners can be held for the crimes of others epitomises the rationale of collective responsibility for Muslims that permeates discourse in the War on Terror

During this last hearing, for example, Jamil Jaffer, the executive director of the National Security Institute, testified that “the terrorist threat today is worse specifically because we withdrew from Afghanistan in the way and manner that we did” because “[terrorist groups] see this ungoverned space as an opportunity to once again consolidate their efforts and fight the West”.

Demonstrating a complete lack of accountability, he suggests the problems that the US left in the war’s aftermath should be used to adjudicate whether or not to release prisoners. This position is buttressed by the logic that since some former prisoners have become members of the Taliban government, anyone now released from Guantanamo may enlist and challenge the United States.

If the prevailing logic of collective responsibility is applied to Muslim prisoners as a function of the global reach of the US’s state violence, instead of being based on the merits of each case, then Guantanamo will always remain open and occupied.

A moral failure

For the collective psyche of the United States, closing Guantanamo is ultimately about finally facing the ways Guantanamo gives the lie to the values and principles at the heart of American identity. For a start, Americans must face that they endorsed forcing hundreds of Muslim men and boys into a dehumanising prison, where torture was de rigueur, to provide themselves with a fleeting sense of safety - and then chose to look away as the abuses and innocence of many prisoners were exposed.

The Biden administration now has the opportunity to act forthrightly and begin the process of not merely closing Guantanamo but reckoning with the collective moral failure that it represents.

A troubling prospect, though, has been raised by recent media reports suggesting that rather than taking “quiet steps to close” Guantanamo, as the administration has claimed, the government is in fact actively adding to the detention facility’s infrastructure by constructing a new courtroom. This addition would all but ensure that the failures of transparency and judicial principle will continue - the features of the new courtroom echo the extreme secrecy that has characterised previous Guantanamo trials, for example, by leaving no room for observers.

Perhaps more important than the whims of any particular administration, however, is the fact that after 20 years, we still cannot seem to name the problem when it comes to Guantanamo. Just as the issue of police brutality can not be solved without addressing the systemic anti-Blackness that perpetuates it, Guantanamo must be seen through the lens of Islamophobia and the context that made it possible, or closure will be little more than an empty gesture.

We must not let Guantanamo close its doors as a way of erasing the legacy of harm it embodies once again from public view. Instead, the US must grapple seriously with the question of how to end the injustice that has been visited on Muslim prisoners and which goes far beyond abandoning the use of a physical structure.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.