Verdict on Sisi's first year in office

The second anniversary of the toppling of former Egyptian President Mohamed Morsi on 3 July warrants an assessment of the performance of the man who ousted and replaced him, Abdel Fattah al-Sisi, who last month marked his first year in office.

It has been a year marked by the continued rolling back of hard-fought freedoms achieved after the 2011 revolution that brought down Hosni Mubarak. Reports from numerous international human rights organisations last month alone highlight the scale of the problem.

Sisi "has presided over the flagrant abuse of human rights since taking office," Human Rights Watch (HRW) said on 8 June, condemning "a lack of accountability for many killings of protesters by security forces, mass detentions, military trials of civilians, hundreds of death sentences, and the forced eviction of thousands of families in the Sinai Peninsula.”

Sisi and his cabinet, "governing by decree in the absence of an elected parliament, have provided near total impunity for security force abuses and issued a raft of laws that severely curtailed civil and political rights," HRW added.

A week later, 10 international human rights groups accused the authorities of "increasing their pressure on independent organisations in Egypt that receive foreign funding or have criticized government policies".

Ten days after that, the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) said Egypt had "the highest number of journalists behind bars" since the organisation began recording data on imprisoned journalists in 1990. "Journalists face unprecedented threats in... Sisi's Egypt," the CPJ added.

Days later, Amnesty International said Egypt "has regressed into a state of all-out repression," with the authorities "crushing an entire generation's hopes for a brighter future" by "relentlessly targeting Egypt's youth activists".

The government's response to these allegations has been denial , despite overwhelming evidence, and accusing these respected organisations of bias and of conspiring against the state.

Meanwhile, American, European, Asian and Arab governments, among others, are turning a blind eye to these abuses for the sake of weapons sales, energy contracts, trade deals, political influence and counter-terrorism partnership with the Arab world's most populous country and one of its most geo-strategically important.

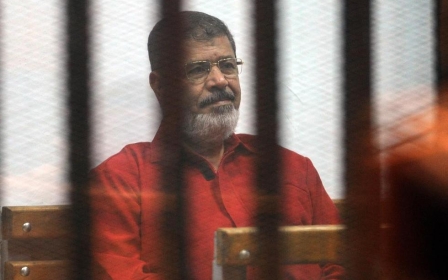

For example, last month Sisi was invited to visit Britain by Prime Minister David Cameron, a day after Morsi was sentenced to death in what human rights groups said was a fundamentally flawed trial.

Unrest

Sisi's inauguration speech made no mention of democracy or human rights, but his promise of "a more stable future" has gone unfulfilled as the military man's iron-fisted approach to the country's problems has exacerbated unrest and violence.

Protests by Morsi supporters continue, but the crackdown against them has widened to target all manner of dissent, including from those who initially supported Morsi's overthow but have grown disillusioned with Sisi and angry at the re-emergence of Egypt as a police state. This has increased opposition to the current president, albeit among two distinct and opposing camps.

Military campaigns to quell violence have failed, with militant attacks nationwide increasing in number and scope. Take the events of the last week alone. Seventeen soldiers were killed after simultaneous assaults on military checkpoints in North Sinai, described by Reuters as "the deadliest fighting in years in the restive province".

In Cairo, at least three people were killed and others wounded by explosives near a police station, a policeman was killed in a gunfight with militants, and Egypt's top public prosecutor, Hisham Barakat, was killed by a car bomb, becoming the most senior state official to be killed by militants since Morsi's ousting.

Sisi's reaction to Barakat's murder typifies the president's ignorance of cause and effect under his rule. Sisi vowed that death sentences would be carried out, but it was the judiciary's readiness to, as HRW put it, to "sentence the government's opponents to death with barely any regard for due process" that led to militants threatening to attack judges.

Long-term unrest in the Sinai has developed into a full-blown insurgency, with militants there pledging allegiance to the Islamic State (IS) late last year. The government's response has been to scapegoat Hamas, the Palestinian faction that rules Gaza, by accusing it of sending weapons and fighters across the border.

This despite enmity between IS and Hamas, the latter's military strength being heavily depleted by Israel's onslaught last summer, and Gaza being tightly blockaded by Egypt and Israel.

Cairo last year decided to build and considerably expand a buffer zone along the border with Gaza, entailing forced mass evictions of Sinai residents and demolition of their homes, the scale of which Amnesty described as "astonishing". This has only galvanised the insurgency - which has been able to feed off the newly increased list of Sinai residents' grievances - and revealed the baseless nature of the allegations regarding Hamas's role.

The economy

The rise in violence has devastated the economically vital tourism industry. Last month saw a suicide bombing near the ancient Karnak Temple in the city of Luxor - a major attraction in Egypt - as well as a thwarted attack in Giza, the site of the famous pyramids.

Elsewhere, the economic outlook is mixed. The economy is projected to grow by up to 5 percent in 2015/2016, unemployment has fallen slightly, ratings agencies have been generally positive about Egypt, and Sisi has managed to attract considerable amounts of foreign investment despite the country's many problems.

However, unemployment is still high at 12.8 percent (it was 9 percent in June 2010), as is inflation. Due to subsidy cuts and tax increases, Egyptians are hurting from higher prices for essential products such as fuel and food, as well as for cigarettes and alcohol, among other everyday items. Additionally, the economy is being propped up by billions of dollars in Gulf aid.

Sisi is likely to continue, if not intensify, his crackdown on dissent, safe in the knowledge that opposition to him is divided and suppressed, and that he has the backing of the military, a pliant media, key foreign allies, and much of a population that either supports him or is tired of further turmoil.

However, if Sisi does not genuinely address growing public grievances in ways other than through a security lens (which is not working anyhow), he will be seen increasingly as just another propped-up Arab autocrat detached from the people and maintaining power at all costs. The last few years have shown that Arabs will not indefinitely tolerate being ruled that way.

- Sharif Nashashibi is an award-winning journalist and analyst on Arab affairs. He is a regular contributor to Al Arabiya News, Al Jazeera English, The National, and The Middle East magazine. In 2008, he received an award from the International Media Council "for both facilitating and producing consistently balanced reporting" on the Middle East.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Photo: Egyptian President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi (C) talking to media as he stands with the family of Egyptian state prosecutor, Hisham Barakat on 1 July 2015 (AFP)

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.