The waning relevance of Iran's reform movement

Iran's reform camp is in a deep crisis of relevance and legitimacy. Many proponents who once believed in its promises of "religious democracy," and who campaigned for reformist politicians during election cycles, seem to have lost faith in the movement's ability to deliver.

The rapidly fading purchase of the reform project has tectonic implications for where Iran is headed in the domestic and foreign policy spheres, partly because Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei is aging - he is 79 - and preparations for succession to the highest office in the Islamic Republic are quietly underway.

The demise of reformism also means further homogenisation of Iranian politics in favour of hardliners and conservatives. This could perilously strip democratic institutions of governance or the "republican" component of the state - such as periodic elections, which reformists have always promoted - of their substance and meaning.

Decreasing popularity

"Do you think people will ... participate in the next elections?" former president Mohammad Khatami, widely seen as the spiritual leader of the reform movement, pointedly asked in a rare meeting on 6 March with a group of reformist parliamentarians. "I believe it is unlikely, unless we witness evolution in the coming year."

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Iran's next parliamentary elections are scheduled for spring 2020.

The rapidly decreasing popularity of reformists is not simply due to the relentless efforts of their more powerful hardline rivals - mostly controlling unelected institutions of the state, such as the Supreme Leadership, Revolutionary Guards, judiciary and Guardian Council - to stymie reform-oriented plans. It primarily lies in the lukewarm and hypocritical performance of the reformists themselves.

The reform camp is like a 'store with a pretty front but nothing inside except slogans'

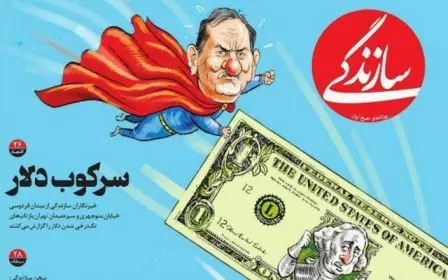

While the reform camp usually criticises its "principlist" opponents for their leading role in Iran's systematic corruption and economic mismanagement, a number of reformist figures are either directly implicated in, or closely affiliated with, large-scale embezzlement, rentierism and nepotism cases.

The latest such instance, which involves €6.6 billion ($7.5bn) and has been locally dubbed as "the greatest scam in Iranian history," has drawn attention to Marjan Sheihkholeslam al Agha, a reformist-cum-conservative journalist who once ran for parliament on behalf of Iran's most influential pro-reform party "Islamic Participation Front". The party was suspended and later outlawed in 2010, in the wake of June 2009 "Green movement" protests.

Other pro-reform figures implicated in major sleaze and scam dossiers include President Hassan Rouhani's brother; Mahdi Jahangiri, First Vice President Eshaq Jahangiri's younger brother; and Shabnam Nematzadeh, the former industry minister's daughter, among others.

'Hypocrisy and arrogance'

The reform camp is like a "store with a pretty front but nothing inside except slogans," a Tehran-based journalist said in an interview on condition of anonymity. "Many reformist figures have turned into dealers and speculators. Hypocrisy and arrogance are among reformists' worst characteristics."

Yet, the reformists' fall from grace seems to be more rooted in politics than in economics.

After the brutal suppression of the 2009 Green Movement, which led to the marginalisation of reformists, many pro-reform groups tried to gradually close ranks with their traditional nemeses, aiming to regain power and influence in state politics. Reformists changed their original identity as a legitimate opposition force, and accommodated more status-quo tendencies to remain politically relevant.

Accommodation strategy

The first signs of the new accommodation strategy emerged when reformists supported a number of notoriously conservative candidates, such as Mohammad Emami-Kashani, Tehran’s interim Friday prayer leader, and Mohammad Reyshahri, former minister of intelligence, in the 2016 Assembly of Experts elections.

Meanwhile, reformists and their "centrist" allies did little to secure the release of Green Movement leaders Mir Hossein Mousavi and Mehdi Karroubi from house arrest.

By the end of 2017, accommodation of hardliners had practically given way to appeasement. The moment of truth came when popular protests over poor living conditions erupted across the country in early 2018. One of the sobering slogans the "livelihood" protesters chanted was "reformist, principlist, the game is over," highlighting the extent of frustration and fury against the ruling elite, regardless of their political leanings.

In a highly controversial move, most pro-reform politicians, including former president Khatami, condemned the widespread demonstrations as a subversion plot hatched by Iran’s foreign enemies and anti-regime groups bent on overthrowing the Islamic Republic.

Some reformist figures disagree with this representation of events. "Reformists did not take a stance against the January 2018 protests. This is a wrong picture painted by anti-regime media," Emad Bahavar, head of the youth wing of the pro-reform Freedom Movement of Iran, said in an interview with MEE.

Bahavar was arrested in 2009 as part of the state crackdown on Green Movement protests and released after serving five years in jail.

"What some reformists objected to was efforts made by radical and subversive groups to take advantage of people’s economic problems and channel [their grievances] into violent and blind riots, with the ultimate aim of overthrowing the regime," Bahavar said.

Growing tensions

Nonetheless, rejection of "livelihood protests" was widely perceived as a political attempt on the part of reformists to demonstrate their loyalty to the state and win over the hardline leadership's approval. In so doing, reformists distanced themselves from their traditional support base among middle- and working-class people, and thus lost a key source of leverage against the hardliners.

"Reformists treated the January 2018 popular protests in a disingenuous and instrumental manner, as they wrongly thought the rallies had been staged by the hardliners [to bring down the Rouhani government] or anti-regime groups such as Mojahedin-e Khalq (MeK) and monarchists," Abdollah Momeni, a prominent reformist figure and former political prisoner, told MEE.

State politics in Iran have swung rightward, partly as a consequence of reformists' shrinking relevance and legitimacy

"This unprincipled and counter-reform treatment created the impression that reformists were trying, in conjunction with principlists, to consolidate authoritarianism. It cost them their credibility in the society."

Meanwhile, growing tensions with the US and its regional allies have not helped matters. The Trump administration's withdrawal from the nuclear deal last May and the reimposition of sanctions against Tehran undercut the Rouhani government's "moderation project" at home.

With increasing international pressure on Iran and intensifying polarisation of its foreign policy debate, hardliners appropriated the nationalist discourse, compelling their reformist opponents to adopt similar stances so as not to appear soft, weak, or even worse, unpatriotic in public.

'Rejected by the state'

There is little doubt that in recent years, state politics in Iran have swung rightward, partly as a consequence of reformists’ shrinking relevance and legitimacy.

Late last year, Khamenei appointed Sadeq Amoli Larijani, a hardline politician and former head of the judiciary, as the new chairman of the Expediency Council, a body tasked with resolving deadlocks and disputes between parliament and the Guardian Council.

To further consolidate his favoured political camp's grip over state institutions, Khamenei installed conservative cleric Ebrahim Raisi as the new judiciary chief on 7 March, despite - or perhaps because of - his infamous role in overseeing the mass execution of political prisoners in the 1980s.

"This shows the state’s [continuing] penchant for hardline and counter-reform forces," Momeni noted. "In other words, reformists have ended up as the main losers, rejected by the state and rebuffed by the society."

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.