Why celebrated artist Baya is much more than Algeria's Picasso

The much-celebrated Algerian artist Baya recently returned to centre stage of the art world through an exhibition of her paintings at L'Institut du Monde Arabe (Arab World Institute) in Paris.

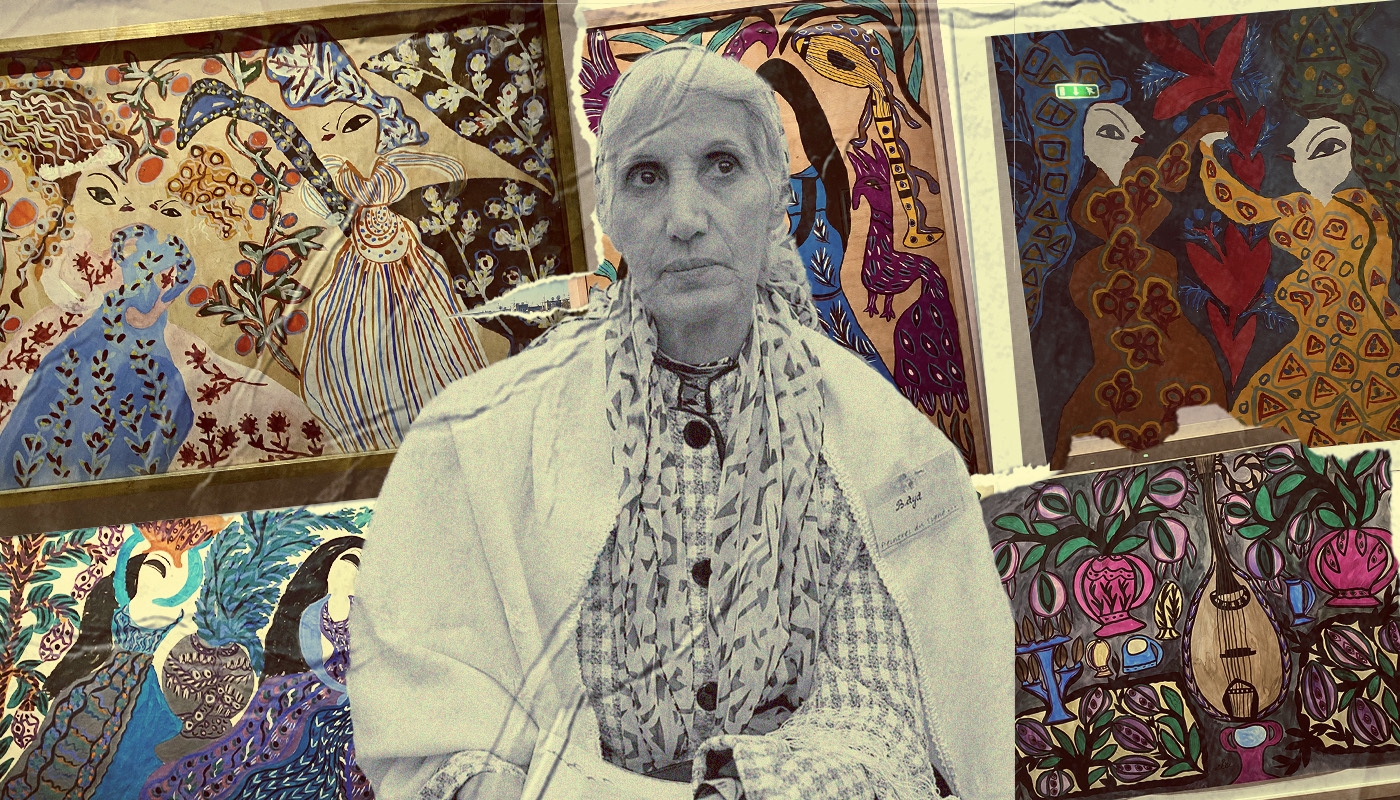

Almost 25 years after the death of an icon whose work transports you to a dazzling realm of (strictly) women, nature and emancipation - illuminated by bright colours - lively conversations about her impact continue.

An important question that continually arises is how the orientalist gaze shaped western reception to her chefs-d'oeuvre. When the background on which her masterpieces are hung is the not-so-blank and neutral Arab World Institute, it is perhaps unsurprising.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

The institution, established by former French presidents, is now headed by a former minister and supporter of Israeli normalisation, Jack Lang, who not too long ago called hundreds of Arab intellectuals, artists, famous directors and public figures "sheep" for opposing the institute's relationship with Israel.

Indeed, in a month that marks Unesco's World Art Day, Baya's story reminds us that, for many artists across the Global South who were "discovered" under colonialism, their legacy is still marked by the period. Where their work is exhibited therefore continues to be a highly political matter.

An overlooked 'queen'

Baya Mahieddine, born Fatma Haddad in 1931 in Algiers, was encouraged to express her creativity by her adoptive mother, Marguerite Caminat, a settler during France's colonisation of Algeria, who was herself an artist.

Through her art, Baya possessed the power to translate her desired reality. She used gouache (an opaque watercolour) as her primary medium, and she depicted a world without men, full of vivid images of lush natural landscapes inhabited by richly dressed women.

Many of her works included red-lipped, smiling women in colourful clothes, adorned with classic Maghrebi motifs, which feel like an ode to the bright, patterned Kabyle dresses that women in the region wear to this day.

The flowers and fruit present a sense of joy and abundance. The birds and other animals she featured embrace a wild and flourishing nature that defined many of her paintings. In this untethered world, a female figure is foregrounded - one who is as determined and independent as the young Baya herself.

It was clear from early in her creative journey that Baya's art could not be contained and needed to be seen by the world. She was catapulted onto the Parisian art scene as a teenager in 1947 - just shy of 16 years old - when an exhibition showcasing her art opened in a gallery in Paris.

The reception to her work was overwhelming: she was a hit. The likes of Andre Breton, the father of surrealism who was taken by her dream-like pieces, wrote: "I speak not like so many others to lament an end, but to promote a beginning. The beginning of an age of emancipation and harmony, in radical rupture… And, of this beginning, Baya is queen."

However, despite Baya's obvious influence on renowned artists who are still globally celebrated, the Algerian art queen has received little credit. This is certainly the case with Picasso, whose collection, The Women of Algiers (1955) was inspired by her after he invited her to work with him in 1948. Given the man's reputation as a misogynistic narcissist, it may not be news to many, but it continues to serve as a reminder that history isn't exactly on the side of a poor, young Berber Algerian girl living under colonialism.

Nevertheless, Baya would respond to what can only be described as a diminishment of her role in the French and European art movements at the time with a sense of effortless empowerment: "At home, my mother had Braque and Matisse paintings. These are painters I love, who touch me deeply, but I don't know if I can say that I was influenced by them. I have the opposite impression: that they borrowed colours from me."

The evolution of those artists' styles was not lost on Baya. Pulling no punches, she factually states: "Painters who didn't use Indian pink started to use it. But Indian pink and turquoise blue are Baya's colours. They have been present in my paintings since the beginning, they are colours that I love."

Yet, throughout her life, and even after, Baya was often described through the lens of orientalism, pigeonholed by western critics as "mysterious" or, patronisingly, "naive".

This was no doubt the outcome of her context. She worked against a backdrop of racist and orientalist depictions of Muslim and North African women, who were imagined in homogenous and disempowering ways - fetishised and represented as submissive, sexualised objects. From their dress (veils and hayeks) to their homes (casbahs, riyads and hamams), they were the target of disturbing and even violent obsessions within the art world, settler society and the occupying French state.

Nevertheless, Baya, true to her nature, often rejected the labelling of her style and work - and broke through such constraints - calling what she created: Baya-isme.

It speaks volumes that, since her first exhibition in Paris, the most notable expositions of her works have also taken place across the West.

De-centring the West

In truth, the hosting of her masterpieces by the World Arab Institute is especially bittersweet because in a post-independent Algeria, following global movements of decolonisation, we are still asking: why does Paris continue to hold such worth within the cultural world?

The understanding of Baya's complex life and work is still very much surface-level and continues to be dominated by the western eye

I visited the exhibition with considerable apprehension. I was both overjoyed to be immersed in her world to the point that I could barely contain my emotions and saddened by the fact that I had not felt this in our shared homeland, Algeria.

To boot, the list of individuals and institutions that own and shared pieces of her work for the exhibition is an overwhelmingly Eurocentric collective.

When I was a young girl, I was lucky enough to be within touching distance of one of her paintings when we visited my aunt's friend, who had it perched on a chest. It immediately captured my fascination, and when I naively asked whether the owner had painted it, I was told it was created by "Algeria's Picasso".

Without even knowing her story but having a rich enough understanding of Algeria's liberation struggle, it felt like a knife to the heart that a European artist - Picasso, no less - would be used as the gold standard to appraise an Algerian artist's worth.

Later knowing the two artists' history made the politics of that entire experience even worse.

Such attitudes reinforce what decolonial author Ngugi Wa Thiong'o would refer to as the need "to move the centre from its assumed location in the West to a multiplicity of spheres in all the cultures of the world".

This becomes especially urgent when we consider what role these western institutions continue to play in advancing imperialist endeavours. Last year, L'institut du Monde Arabe was rightly criticised for its normalisation with Israel, for example.

Similar to the historical experiences of Algerians who fought France's 132-year occupation, Palestinians have been opposing the colonisation of their land, apartheid practices, the expansion of illegal settlements, forcible displacement and expulsion and fatal violence for almost 75 years. It is rich, then, that an institution claiming to represent the cultural and intellectual riches of the entire Arab world is legitimising a state that seems hellbent on destroying the existence of Palestine altogether.

It betrays the essence of Baya's depictions of liberation and, I would say, is even disrespectful to her creative expression. These contradictions also raise another issue: Baya's own doorstep.

Where, oh where, is the Algerian state when it comes to holding up the artist's contributions to the world? I have seen very few of her pieces in major galleries in Algiers that felt themselves quite abandoned and under-resourced. I've certainly yet to witness such a coordinated, months-long internationally mediatised affair as that of the World Arab Institute. There seems to be no good reason that an oil-rich country from which a world-class artist hails would invest so little in cultural programmes.

The understanding of Baya's complex life and work is still very much surface-level and continues to be dominated by the western eye. This woman who from an intimidatingly young age, after having endured a tragic childhood and losing both her biological parents, knew the world she wanted to dive into - and painted it. This artist, who stopped painting for a decade to birth six children, and who seemed untouched by the omissions of her impact on centre of the art world, still has so much to offer us today - especially as women, Algerians and artists.

Following all that unravelled in Algeria after 1962, including the dark decade from the end of the 1980s, during which a bloody civil war had particularly targeted reporters, artists and other cultural pioneers of the country, maybe it is expected that icons like Baya fell through the cracks. That said, the women (and artists) of Algeria are all too familiar with being written out of history.

But we cannot accept this as a continued reality.

Perhaps it will take for some of us to be brave enough to demand that Baya's legacy - in a decolonial context - finally take centre stage, whether it is through schooling, art institutions or state celebrations. Just as she unapologetically stepped onto her first exhibition with bare feet, unphased by what judgement might follow, we must draw strength from our convictions that "Baya is queen".

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.