Hamja Ahsan: 'I’m trying to reclaim fried chicken for Muslims'

The seeming increase in the number of halal fried-chicken shops over the summer in the city of Kassel, along the banks of River Fulda in central Germany, may have raised eyebrows among locals and tourists alike.

Despite a jump in apparently new shop signage, there has not been an unexpected influx of Muslim migrants; a community of Turks has been living in the city since the 60s and they were joined by refugees from Iraq and Syria during the 2015 refugee crisis.

Once home to the Brothers Grimm and considered the birthplace of the modern fairy tale, another story is being told in Kassel.

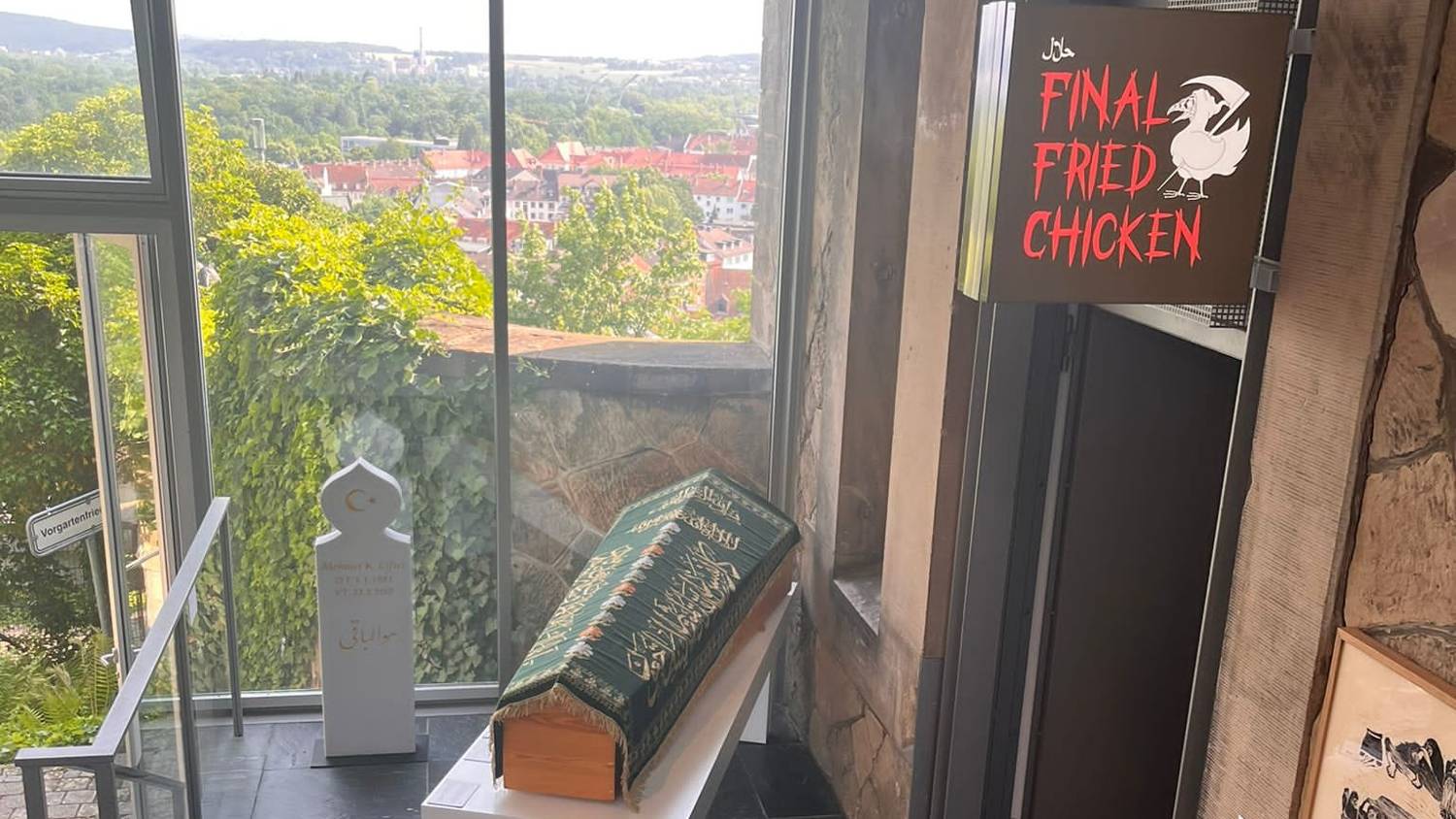

The 14 colourfully designed new LED signs jut out from eight venues, including the 18th-century Fridericianum Museum and the Museum fur Sepulkralkultur, a museum focused on death.

One reads "Kaliphate Fried Chicken ‐ Feeding The Ummah Since 1924", while another reads "Mmmoors ‐ Moorish Fried Chicken!".

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

The tongue-in-cheek signs play on popular fried-chicken shop names, but people looking for a late-night meal will be disappointed, as they are part of artist and activist Hamja Ahsan's latest conceptual art project.

Born in London in 1981 to parents of Bangladeshi origins and raised in the district of Tooting, Ahsan has established a reputation for using satire and alternative realities to address societal issues.

The artist is one of 1,500 exhibiting their works at the prestigious Documenta 15 art festival, which once drew the likes of Pablo Picasso and Henri Matisse.

Running since 1955, the event takes place once every five years, when Kassel is taken over for 100 days of art. The 2022 edition started on 18 June and runs until 25 September.

Documenta has long been associated with participatory art, and Ahsan's dark humour has comfortably found its own space within it.

His art, he says, "recreates the ubiquity of eating fried chicken" and "reflects the incongruity and absurdity of identity politics".

"I wanted to be ironic, to create space for the rising phenomena of the chicken shop and what it now symbolises. Many see the rise of chicken shops, especially in the UK but also in other western European countries, as the rise of Islamification.

"But what these places actually offer are spaces that are beyond borders, beyond nation states, beyond ethnicities and beyond languages. Fried chicken has the power to do that."

Ahsan says his work is inspired by the British comedies he watches, such as Goodness Gracious Me and the more recent Man Like Mobeen.

His biggest influence was the 70s hit show Citizen Smith. In it, a young urban revolutionary, who also happens to be from Tooting, attempts to emulate his hero, the Marxist revolutionary Che Guevara.

The show's main character, Wolfie, creates a resistance group called the Tooting Popular Front, which got Ahsan thinking and led to the creation of his own satirical movement-slash-chicken shop, PFLFC ‐ the Popular Front for the Liberation of Fried Chicken.

The fried-chicken shop and the British Muslim

Ahsan's other source of inspiration is, of course, the fried-chicken shop itself and his own experiences frequenting them in his youth.

Today thousands of halal chicken shops pepper the UK's urban areas, with more than 8,000 in London alone.

It's not unusual to see dozens on the same stretch of road, directly competing for customers by offering the lowest-price chicken.

The culture of the fried-chicken shop got its start in inner-city areas of the US, making its way to the UK after the first branch of Kentucky Fried Chicken (KFC) opened in 1965 in the northern English city of Preston.

Decades later, local entrepreneurs were offering their own versions of the classic fast-food staple, with the launch of home-grown brands such as Chicken Cottage, now in its 28th year, and Sam's.

The former was immortalised in British Muslim youth culture in the comedy movie Four Lions, where one of the hapless members of an Al-Qaeda-inspired group chastises westerners for choosing KFC over the better-value Chicken Cottage.

In the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis, the fried chicken has become a billion-dollar industry, fuelled by the popularity of meals as cheap as a pound ($1.15) .

Crispy coated chicken, blanketed with thick salty fries, offer a filling and cheap dining experience for those seeking a quick fix after a night out or for ravenous school children on their way home.

A scene synonymous with the fried-chicken shop is a crowd of teenagers gathered around the laminated tables in a takeaway, dissecting school politics.

"Fried chicken is a magical opiate-like substance, it's almost like an antidepressant, it cures a lot of stress, and it's better to be addicted to fried chicken than to be addicted to alcohol or drugs," Ahsan says.

"There's a deep sense of identity found in chicken shops. It's a place where people can integrate and assimilate.

"It'd be the only place open at 1am that would welcome you. Muslims have seen it as a safe space, as the food is halal, there's no alcohol and the people running the shop are usually Muslim too, so it builds a sort of allegiance.

"People have had political debates here, discussed deep issues, white people have even converted to Islam and taken the shahada [Islamic declaration of faith] in a fried chicken shop."

Some shops, such as City Fried Chicken in Whitechapel, even play the adhan [call to prayer] when it's prayer time.

But there's also a social stigma attached to the eateries, equated with inner-city deprivation and proletarian aesthetic.

'White people have even converted to Islam and taken the shahada in a fried chicken shop'

- Hamja Ahsan, artist

This sentiment was reflected in Sadiq Khan's comments when he was running for mayor of London in 2016.

"We've got too many chicken shops in our town centres," he said, further lumping the shops together with pawnbrokers and betting houses.

Less to do with the actual establishments themselves than the economic milieu in which they are found, the fried-chicken shop has become associated with the more unpleasant realities of urban life.

Gangs have used fast-food outlets to recruit children with the promise of free food in exchange for carrying drugs.

In 2019, the UK's Home Office distributed #knifefree slogans in empty fried-chicken boxes in its bid to tackle knife crime.

Islamic activism

The aspect of fried-chicken shop culture most influential in Ahsan's work is its intersection with religious activism.

Throughout the 90s and 2000s, fried-chicken spots were a favoured hangout for activists with the Islamist organisation Hizb ut-Tahrir to meet up with potential recruits. Also in the 90s, British Muslim volunteer fighters in the Bosnian War would hold study circles in fried-chicken shops.

Ahsan has worked with and met former-Guantanamo detainees through his human rights campaigns who have spoken of missing simple food such as fried chicken and fries.

These very real and personal accounts helped Ahsan conceptualise a series of provocative khutbas, or religious sermons, as part of his Documenta exhibition. Titled "Theological Positions around Fried Chicken", there are currently five, one in which he features himself.

Posing as a militant activist, Brother Hamza from the Al-Badr Resistance Squad discusses the virtues of Halal Fried Chicken cultures amid the context of the "war on terror". His mock character only attends mosques to recruit members to join his resistance.

Ahsan describes how good the first bite of chicken tastes after being unjustly detained in Guantanamo, before offering his thoughts on chicken-shop names: "Astaghfirullah [I seek forgiveness from God] to the ones with names after places in America, places like Tennessee Fried Chicken and Dallas Fried Chicken.

"You can say something about the imam of the local community by looking at the names of the local chicken shops... Al-Badar Fried Chicken, Al Ikwhan Fried Chicken - the brotherhood and fraternity."

Ahsan says that in his youth he'd walk past these very takeaways in east London. Their Arabised names pulled him in and allowed him, he says, "to rediscover my lost Islamic identity. These shops would have the Islam channel on in the background. I was quite secular at the time, and they drew me in."

Muslim televangelists, along with 90s khutbas on YouTube, informed Ahsan's research for his dry-witted short films, streamed through the Documenta social media platforms.

Fellow artists and academics known to Ahsan agreed to get into character and improvise mock-philosophical performances on the pros and cons of halal fried chicken.

It's through these that Ahsan's black humour, reminiscent of Four Lions, really shines.

In another of the khutba sketches, the character of Sufi Sheikh Yusuf Iskender Gillingham Bey, played by academic William Barylo, became Muslim "as it was a fun thing to do at the time".

Barylo's character was based on a blend of British Muslim scholar TJ Winters, for whom Ahsan says he has a lot of respect, and the writings of Robert Irving's disconnected journeys through Africa, where everything is hyper-exotic.

"As a white person, you get lots of admiration when you travel to countries like Pakistan, and if you're on social media you get so many followers.

"Shops may be greasy, grease dripping on the wall, but it is authentic, you go there for the smiles of the bossman... people who haven't been contaminated by the modern excess of the real world."

The word "bossman" here refers to a popular colloquialism used by customers for fried-chicken shop proprietors as well as by takeaway staff for customers.

In another video, sister Jameelah Abdul Wakeel, a character played by poet Hodan Yusuf, takes on the role of an American relationship counsellor.

"They say marriage is a bed of roses," she starts before launching into an invective against Muslim men.

"Let me be honest sister, your beds are covered in fried chicken. Bossman asks if he's a breast man, a leg man or thigh man, auzubillah! [I seek refuge in God!] They are having conversations about breasts in the streets.

"Your men are too far gone. They are in love with this chicken, you're competing against something you can never be."

Facing right-wing 'cancel' culture

Despite its clearly satirical tone, Ahsan's conceptual art project has been criticised from the right and far-right.

His references to the Palestinian cause, such as "Al‐Aqsa Fried Chicken", irked supporters of Israel in Germany, who said the works were imbued with antisemitic themes.

In a separate incident, a number of Ahsan's installations at the WH22 venue, a former night club, were vandalised in late May with graffiti that read "187" and the name "Peralta".

The former is a slang term for murder, while the latter refers to Spanish neo-Nazi Isabel Peralta, who made headlines in early 2022 when she was barred from entering Germany.

With regard to the response from Zionist groups, Ahsan believes his support of the Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions movement is the likely motivation for the criticism. The campaign, which calls for sanctions against Israel over its human rights abuses against Palestinians, has been condemned by the German parliament as "antisemitic".

"I get messages every day on my social media accounts, I get nasty threats, and have been told that I should be removed and replaced with an Israeli artist," Ahsan says, further asking: "Why can't I create this art as a British brown Muslim? It's a parody, like Chris Morris's Four Lions.

"But people are attacking me as I support BDS. In Germany they have an Orwellian crackdown on Palestinian solidarity."

When it comes to neo-Nazi graffiti, Kassel has been targeted previously by far-right activists.

In 2018, the anti-immigrant Alternative for Germany party demanded that a 16-metre obelisk, which was exhibited in Kassel as part of Documenta 14, be taken down. The structure, which was relocated as a result, was emblazoned with the Biblical verse: "I was a stranger and you took me in."

But such far-right intimidation will not stop Ahsan from expressing himself through his art.

"I'm just trying to reclaim fried chicken for brown Muslims," he said.

"Through all the fried-chicken hype in rap songs and YouTube shows like Chicken Shop Date and The Pengest Munch, Islam is written out. But most of these places are run by Muslims and frequented by Muslims. That needs to be recognised."

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.