The Oracle of Siwa: How a remote oasis in Egypt drew history's most powerful men

The isolated oasis of Siwa, thirty miles east of the Libyan border in Egypt’s Western Desert, has featured throughout history as a site of desire and contest.

If its old "Mountain of the Dead" could speak, it would relay dreamlike tales of foreigners who attempted to reach the oasis and failed, and, for those who did succeed, the short-lived nature of their stay.

Owing to its location in the midst of the Egyptian desert, the landmark has long resisted outside influence.

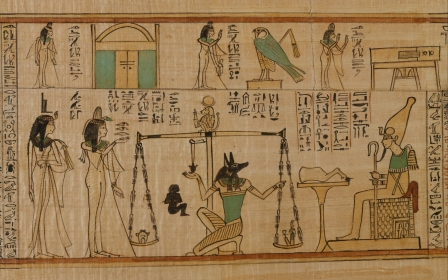

A temple dedicated to the god Amun (Amun-Ra), a prominent deity in the Egyptian pantheon, was established some time around the 7th and 8th centuries BCE, and additional traces of Ancient Egyptian culture in Siwa were recorded in subsequent centuries.

The oracle of the temple, while not on the scale of others in the Nile valley, held a magnetic allure, which attracted jealousy and envy among the most powerful ancient kings.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

People would come for questions and prophecies and priests acted as interpreters of the divine.

Heroes were said to have visited the oracle. The temple, where ceremonies and worship took place, struck many outsiders with its physical beauty.

Alexander, Cambyses and the 'divine oracle'

The Achaemenid king of Persia, Cambyses, son of Cyrus the Great, sought to consult the oracle of Siwa to legitimise his 525 BCE conquest of Egypt.

According to the Greek historian Herodotus, Cambyses decided to redirect 50,000 soldiers to destroy Siwa’s temple and enslave the population of the oasis, after the oracle refused to endorse his ambitions.

Stationed in Luxor, the Persian king's army lost their bearings inside the desolate 500 miles separating the Upper Egyptian city from the oasis.

Experts still debate whether an entire army perished, as Herodotus claimed, and if so, whether a sand storm that caused their demise.

But what we can take away from the historian’s reports is that even a king needed the blessing of a remote oracle in the Western Desert to assert claims of uncontested power.

Siwa was one of the seven most revered oracles of ancient times and the only one that was not Greek.

Its cultural significance radiated across the Greek and non-Greek Mediterranean worlds and it was particularly sought after for knowledge on the fate of political and military ambitions.

And people perceived Siwa’s oracle as less politicised than others, like Delphi, and one that was more difficult to corrupt.

One couldn’t attack or threaten the oracle, as the wrath of Cambyses and his lost army demonstrated, and it couldn’t be bribed; the Spartan general, Lysander, tried to do this, in vain.

Perhaps paradoxically but likely explained by its geographical distance from Memphis, Thebes (Luxor) and other key religious centres along the Nile, Siwa primarily attracted non-Egyptians. No pharaoh ever visited Siwa and claims surrounding Cleopatra’s visit remains uncertain.

Alexander of Macedon, whose mother embraced the esoteric, understood this.

He calculated that he would first need to pay his respects to the oracle and travel to Siwa, or alternatively send a delegation to the oasis town for Egyptians to accept his foreign rule when his army entered the country.

Immediately after founding the city of Alexandria, the Macedonian conqueror chose to go himself and left the Egyptian coastline, unannounced, for the temple of Amun in 331 BCE.

Perseus and Hercules, claimed by Alexander as distant ancestors, were also said to have consulted Amun

While Alexander’s Egyptian kinship had been recognised by the priests of Memphis, it was in the sanctity of Siwa’s temple that a priest declared him the son of Amun. King Alexander then, became a god; a distinction that mattered in pious societies, like that of Egypt.

The Greeks equated Amun to the chief of their Olympian gods, Zeus. Offerings to Amun were placed in the Acropolis in the 4th century BCE and temples dedicated to Amun could be found in Greece.

Alexander may have remembered the Greek teachings of his former tutor Aristotle, in which the philosopher may have conveyed the commonly-held view of the time: that Egyptian culture was vastly more sophisticated than that of the Greeks, and its rituals and beliefs preceeded those held by them.

The Macedonian may have wanted to succeed where Cambyses failed. He may also have recalled how revered Greek poet Pindar had sent praise to Amun in a hymn carved in the temple.

Perseus and Hercules, claimed by Alexander as distant ancestors, were also said to have consulted Amun.

Augurs, or signs foreshadowing a great destiny, surrounding Alexander’s birth may have nurtured an interest in mystical quests, especially if they granted divinity and immortality.

Some archaeologists, such as Liana Souvaltzi, still claim that Alexander’s tomb is located somewhere in Siwa.

Asserting modern Egyptian sovereignty

Residents of Siwa likely continued practising syncretic religious rituals long after antiquity and it wasn’t until the time of the Fatimids, around the 12th century, that they opened to Islam.

Exposed to attacks by Bedouin tribes, Siwans left the older site of Aghurmi, where the temple of the oracle is located, to establish a new walled settlement, known as Shali ("the town"), with 40 men and seven families in 1203.

An extant manuscript records that some Siwans settled in the eastern part of this new city, while others stayed in the western sections, later to constitute two groups.

Egyptian authority was asserted in 1820, when Muhammed Ali Pasha sent in troops to Siwa as part of his conquest of Libya and Sudan. Several Europeans then travelled to the oasis, amid a trend of Egyptomania and Orientalist curiosity on the continent.

From the early 19th century, expeditions such as one led by the German Consul in Cairo, Heinrich von Minutoli, meticulously recorded important archaeological sites in and around Siwa.

The early photographs from Hermann Burchardt in 1893, also offered precious historical records amidst a climate of regular unrest.

Such instability stemmed from tensions between easterners and westerners inside the oasis, and a refusal to pay taxes to central authorities.

Attempts were also made to record the Siwan language, a sub-group from the Eastern Berber or Tamazight language family which is now estimated to be “definitely endangered” by Unesco.

Abbas II became, in 1904, the first ruler of Egypt to visit Siwa since the time of Alexander. A caravan of over 200 camels accompanied the Ottoman Khedive's visit, which was well received by the local population.

Abbas set out to expand water management and irrigation projects in the oasis but the outbreak of the First World War put these plans on hold.

During the conflict, Siwa was caught between various opposing interests.

On the one hand, there were the British, who occupied Egypt, and on the other, the Ottoman Turks, who protected the influential Sanusi religious order, which was centred in Libya but was also dominant in Siwa.

The Sanusis were involved in a protracted conflict with the Italians, who invaded Libya in 1911. Troops loyal to the order briefly stayed in the oasis with some Siwans even joining their ranks.

Ultimately, the British entered the oasis in 1917, putting an end to hostilities, at least within Siwa.

Following the end of the British protectorate and Egypt’s partial independence in 1922, the country exercised a more determined control over the oasis with the symbolic visit of King Fuad in 1928.

Travelling by car, using the same itinerary as Alexander the Great, King Fuad sought to promote modern Egyptian culture in the majority non-Arab oasis.

He stayed for a day, showing a film for the first time to an assembly of Siwans, ordering a mosque to be completed and initiating the construction of a school.

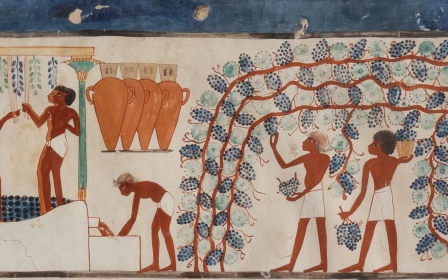

Like Abbas II, Fuad also implemented the latest agricultural techniques to improve crop output in the area around the oasis.

Upon learning that some Siwans practiced homosexuality, through marriage contracts between two men, the king ordered a religious scholar to be sent to Siwa and eventually head the new mosque once completed.

Rommel and War in North Africa

When the Second World War broke out, Siwa took on a strategic importance in the North Africa campaign. Allied troops, including British and Anzac forces, occupied Siwa.

The oasis was closed to non-military visitors except briefly to Egyptian archaeologist Ahmed Fakhry.

When he was finally able to obtain a permit and visit, Fakhry found residents seeking shelter in the caves of the Mountain of the Dead, tombs defaced and artefacts sold as souvenirs. He put down his memories and unparalleled knowledge of the oasis in his seminal 1973 book, Siwa Oasis.

Siwans, on the brink of starvation, welcomed newcomers when Allied forces abruptly left the oasis in June 1942 and a month later, the Italians arrived from Libya by air and road without facing resistance.

Up to 2,000 Italians were stationed in Siwa and German troops shortly followed.

The famed German commander, Field Marshal Erwin Rommel of Hitler’s Afrika Korps, came to visit in September and was received by his own troops, as well as local Siwan authorities.

It was here that Rommel admitted to one of his officers, Major Hans von Luck, that the war was lost.

The Italians left three months after their arrival upon news of the Axis defeat at El-Alamein.

British war artist Edward Bawden captured the atmospheric vista of Siwa during the conflict in evocative, undated watercolours.

In desaturated hues, the painter depicted views of the town itself, showing the Mountain of the Dead and the ruined fortress of Shali, as well as two vignettes of Aghurmi, including one lush with date trees, donkeys and a local man.

Seventeen years after his father's visit, King Farouk visited the oasis in 1945. The times of lavish gifts had passed and the foreign-educated king, only 25 at the time, perhaps lacked Fuad’s gravitas.

Ahmed Fakhry reported a lacklustre visit, in which Farouk asked Siwans who welcomed him whether their social "vices" had at last been suppressed.

Siwa today

A tarmac road finally connected the oasis to the city of Marsa Matruh in 1984 and subsequent tourism has brought more visitors to the Siwa.

Visitors are attracted to Siwa's remoteness, perceived authenticity and its historical aura, as well as its lush palm groves, plentiful natural springs, unique textiles, jewellery, sand dunes, dramatic scenery and ancient ruins.

In 2011, Siwa received an estimated 20,000 visitors annually, representing two-thirds of its total population.

Under renovation since 2018, the fortress of Shali re-opened in late 2020, and a first Amazigh female representative from Siwa, Fathia al-Sanusi, was elected to the Egyptian parliament.

A challenge in a post-pandemic world will be for the Egyptian government and Siwans to preserve their unique local culture, while attracting revenues that will provide the means for people to carry this heritage forward, to future generations.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.