This woman messaged me on Facebook to help flee a life of abuse

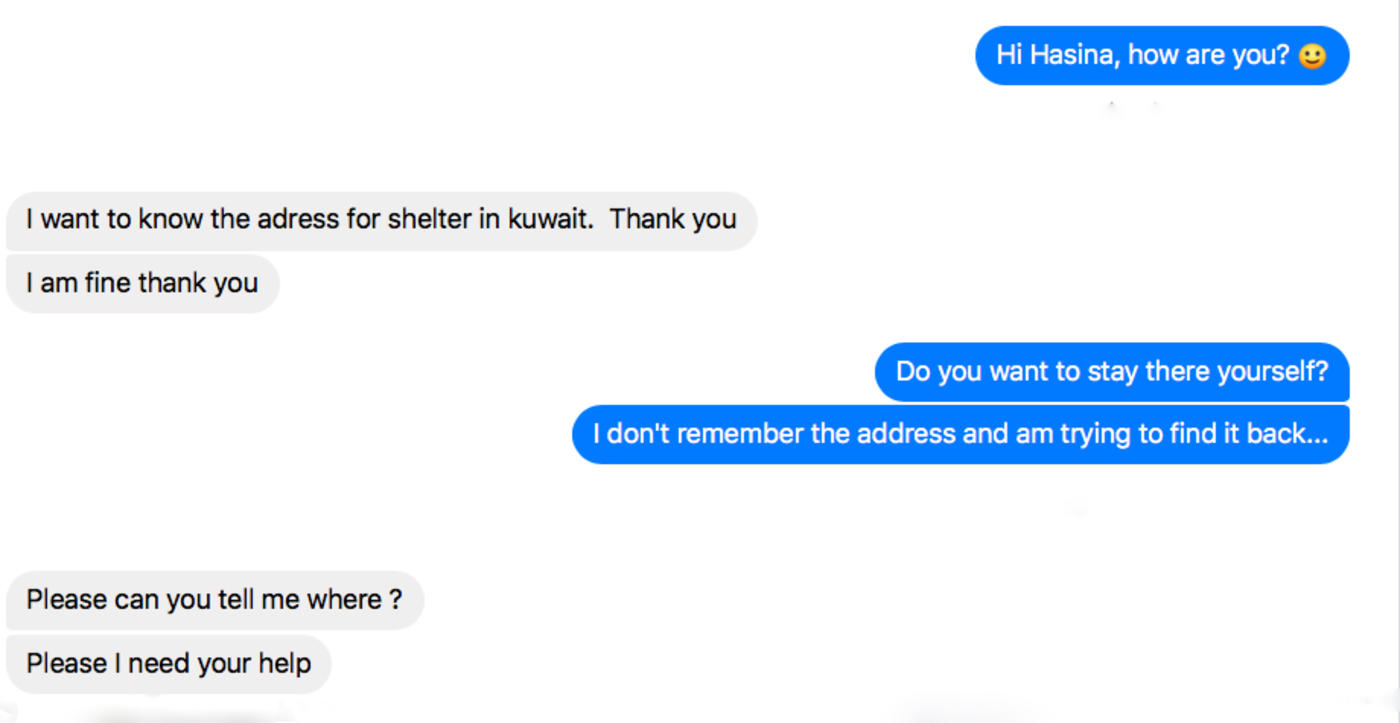

It's a Monday afternoon in January. I'm working at my office in The Hague when a young woman's plea for sanctuary reaches me via Facebook Messenger.

"Good evening Madam," it begins. "I want to know the address for the shelter in Kuwait ... Please, I need your help.”

The woman introduces herself as Eline. She is originally from Madagascar, one of the poorest countries in the world. She does not use her real name on her Facebook account; instead, she goes by the name Hasina.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

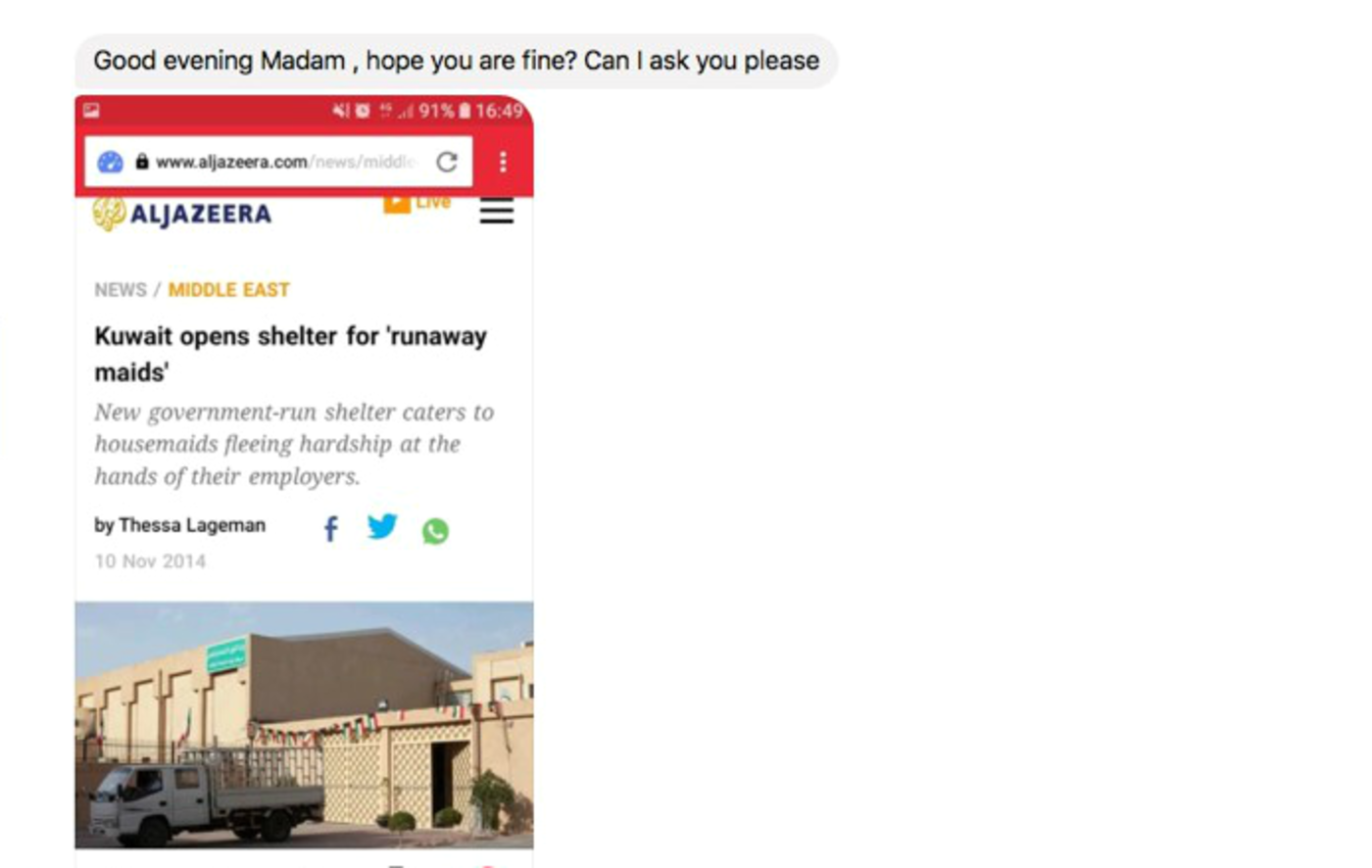

Eline's contacted me because of an article I wrote four years ago for Al-Jazeera about a shelter for "runaway maids" in Kuwait. She's even included a screenshot as a reminder.

"Me and my friend need to go there because the boss want to kill us," she writes. "And one son of my boss touch me (want sex) so I must run away as soon as possible."

I sometimes get contacted about pieces I have published - but not like this. Not five years later. She sounds in danger. She needs help.

Kuwait: Two worlds

Kuwait is one of the world's richest countries and almost everyone employs one or more domestic workers. Some 70 percent of the residents in this small Gulf emirate are migrants: out of around 2.5 million foreigners, there are 648,346 mostly Asian and African domestic workers, employed inside family homes as cleaners, cooks, child carers, elderly caregivers, drivers or gardeners.

In the Gulf region, migrants are bound to their employer via the kafala or sponsorship system. Passports are taken away on arrival and the contract can only end when the employer agrees.

In 2015, Kuwait adopted a law on Employment of Domestic Workers. The maximum number of work hours is set at 12 hours a day with the right to a weekly rest day and yearly paid leave. In reality, few domestic workers have benefited from these rights. Ryszard Cholewinski, a senior migration specialist from the International Labour Organisation, says: "Improved enforcement of these laws is needed."

There is also contempt in Kuwaiti society for migrant workers. Last year Sondos Alqattan, a beauty blogger, provoked anger when she said she was opposed to servants getting a day off and keeping their own passports.

The Kuwait Society For Human Rights said in a report that the Domestic Workers Department, which is supposed to handle complaints by domestic workers against their employers, has admitted it cannot impose penalties on employers for violations.

"All it can do is prohibit employers from recruiting workers for six months," says the report.

The dream of escape

Eline grew up in a village near the town of Ambositra in Madagascar. It's a green hilly area with unpaved roads and only recently has gotten access to electricity. There, Eline toiled in her parents' paddy field.

Some 76 percent of the population of Madagascar live in extreme poverty, according to the World Bank. Eline, like many others, wanted a better future.

Her first job abroad was in Lebanon, where from 2009 to 2012 she was employed as a domestic worker. Eventually, she had enough money to buy a piece of land near her home in Antsirabe, Madagascar and open a small stationery shop. She wanted to build a house as well, but ran out of funds.

'They called me servant and would scream orders at me in harsh voices, even the children'

- Elina, former domestic worker in Kuwait

Then a friend puts her in touch with an illegal job agency in Madagascar, which in turn connects her with an agency in Kuwait run by a Bangladeshi man. She finally secures a job as a domestic worker in Kuwait in 2016.

Over recent years, several stories have appeared in the Madagascan media about domestic help being treated badly in Kuwait and other Arab countries. Since 2013, the Malagasy government has banned people from working in the Gulf as domestic workers, but many women still go.

Arriving in Kuwait in August 2016, Eline cooked and cleaned for a Saudi family of more than 30; four generations in a large two-storey house in the Kuwaiti suburb of al-Andalous.

"They called me khadama [servant] and would scream orders at me in harsh voices, even the children," she says. Her co-workers included a Madagascan babysitter and three Indian drivers. Their diet consisted of rice and chicken three times a day.

Eline had to face the unwanted attention of one of the sons of her employer - and physical abuse. "One of the four sons sometimes tried to touch me when nobody watched. And when my boss discovered I owned a phone, he hit me."

The "agency" in Madagascar had promised Eline $278 a month, an eight-hour workday and one day off a week. Instead, she received $167 a month and had to work more than 16 hours a day - 6am to midnight, seven days a week.

According to the Kuwait Society for Human Rights, 56 percent of domestic workers never get a day off, while 22 percent only do so occasionally. Ninety-two percent of employers confiscate their workers' passports despite it being illegal.

The minimum wage for domestic help is set at 60 Kuwaiti dinar ($197) a month. Kuwaitis themselves earn an average of 17 times that. How much the workers earn depends on their nationality: Asian, and especially Filipino domestic staff, make more than those from Africa.

Beyond the numbers, Eline's experience is common for domestic workers in Kuwait, with many reports of abuse in the media. In 2017, an Ethiopian woman was filmed jumping from the seventh floor to escape her boss. Last year, Joanna Demafelis from the Philippines was found dead in a freezer, sparking diplomatic tensions with Manila over the treatment of its citizens; her employers were later sentenced to death for her murder.

Such cases have not come to an end. In May this year, Constancia Dayag from the Philippines was allegedly sexually assaulted and killed in Kuwait.

How to escape?

A few months before her two-year contract ended, Eline informed the family she would be going home. They were furious and insisted she had to stay for five years. She notified her "agency" in Kuwait she wanted to leave but was told to stay. Eline also emailed her embassy in Saudi Arabia (there is no Malagasy embassy in Kuwait) but received no answer.

So Eline came to me.

Why would the house risk taking in women on the run? Why did the taxi driver take them to this particular family?

Back in The Hague, I go down to the basement to dig up my notes from 2014. After much toing and froing, Eline manages to track down a contact. Eline thought about waiting for her next salary and then fleeing. I suggest she instead go immediately and ask my Kuwaiti friends to collect her, yet most were reluctant or not around.

Then Eline hatches her own plan: she and the babysitter will flee when they put out the rubbish, the only time they are allowed to leave the house. The pair jump in a taxi - despite having no money - but instead of bringing them to the shelter, the taxi driver takes them to another house where the family wants to employ them.

I advise her against staying there, especially given she does not have her passport. Why would the house risk taking in women on the run? Why did the taxi driver take them to this particular family?

At this point the babysitter leaves Eline as she wants to stay in Kuwait a few months longer to earn money and she has a sister who works in another part of town. A friend of mine and his father's driver agree to collect Eline and bring her to the shelter.

The problem of abuse of migrant workers in Kuwait is so bad that foreign embassies - including India, Sri Lanka and the Philippines - run makeshift shelters for workers who have fled. But Madagascar does not have a shelter or an embassy - the nearest in the Gulf is in Saudi Arabia.

The shelter Eline heads for is administered by the Public Authority for Manpower (PAM), which is responsible for domestic workers in Kuwait. It's a former school in Jleeb al-Shuyoukh, an expatriate area near Kuwait International Airport, and it has room for up to 500 women.

Outside the shelter, Eline comes across some women from home. She texts me on WhatsApp: "Im here now , waiting outside for manager . When I came have 6 ladies from Madagascar here."

In total, she says, there are 14 African women sitting at the door, waiting for the manager to let them in. Some say they have been waiting for a week. It's cold, they're hungry and need to use the bathroom. "We hope someone can take us inside the house tonight," she texts. "Bcoz very cold to sleep outside. I told my family soon I will be back."

The next morning, after the door opens, Eline and the other women undergo pregnancy and medical tests. She has no credit on her phone to make calls but has some internet credit to send emails, Facebook and Whatsapp messages. Eline asks me to contact the Madagascar Embassy in Saudi Arabia, but I get no response to my emails.

From inside the shelter, Eline's phone is confiscated because of her messages with me, but eventually she is able to use someone else's. Eline explains to the guard that she contacted me to find out about the location of the shelter. But the guard is still unhappy. "One security is angry on me," she texts. "He tell why u tell everything to Thessa from holland about your situation here."

Eline complains to me via WhatsApp that she is being picked on. "The bad security tell me turn off ur phone. I tell why only 4 me all the ladies u no tell ... He tell i make prblm for shelter talking with holland blablabla."

In the shelter - and no way out

In the shelter time passes slowly. There is nothing to do, Eline says, "just eating and sleeping. The other women are on their phones all day."

The African women, including 60 from Madagascar, sleep on mattresses on the upper floor and the Asians are in beds downstairs. Finally, her phone is returned to her, but all the photos and contact information have been deleted.

"Sometimes we may go to the courtyard," she continues writing, "but usually we are only allowed to leave our room to eat. If you have money, you can call the shop opposite to deliver something. We can't go outside.

“On Fridays, a group of Christians come to pray with us. They also bring toothpaste, soap and sanitary towels."

"Good news!" she exclaims on a WhatsApp video a few days later. Two women from Human Rights Watch have visited, and she now hopes to return home soon.

The researchers later tell me they are working on a report about domestic workers in Kuwait. HRW's women's rights researcher for the Middle East and North Africa, Rothna Begum, says that some of the women she interviews say they have been beaten, sexually assaulted or raped by employers.

"It's a minority, but probably not everyone wants to talk about it." Not all women whose rights are violated reach the shelter, says Begum, because not everyone knows they exist and not everyone can escape.

Eline hears more stories of abuse. A Malagasy woman who also sleeps in Eline's room says she was forced to work from six in the morning until 3am the following day. Her employer only gave her bread to eat and no salary for half a year. When his wife went to Saudi Arabia, the husband raped her.

These stories cannot be verified but accord with the accounts others have given to human rights groups and in numerous press reports.

The president calls

By late January, Eline is starting to become impatient. She sends an email to the Madagascar Embassy with the names and birth dates of the Malagasy women at the shelter, but receives no reply. I also follow up with an email. No luck still.

Then, on 1 March, Eline makes a film with her phone from inside the shelter, asking for help, and puts it on Facebook.

Within an hour, it is shared hundreds of times back in Madagascar. That night it is shown on the national Malagasy TV channel TVM. Shortly afterwards, the Malagasy president, Andry Rajoelina, calls the women via Facebook to hear about their situation.

A delegation from Madagascar visits on 26 March. Before the visit, however, the shelter's manager tells everyone that if their papers are ready and they have money for a plane ticket, then they can go straight to the airport. That way they can avoid spending weeks or months in a police cell for absconding from their employer, which is illegal.

Middle East Eye contacted the Public Authority for Manpower, which runs the shelter under the minister of state for economic affairs, but did not receive a reply by time of publication.

Eline's parents manage to get some cash to her via taxi, hidden between clothes and sanitary napkins. But by the time it arrives, the price of her air ticket has risen beyond her means.

She is moved from the shelter to a succession of police cells, in one of which she shares space with nine other domestic workers.

The location has changed – but her routine has not.

"The same as the shelter, always [the same] food," she writes, "rice and chicken every day, and in the room locked [up] 24 hours."

Back home, wiser

Finally, in late April, three months after fleeing her employer, Eline is able to fly home to Madagascar and then on to her home village to stay with her parents.

'There is little work, and even if you have a job as a teacher or a police officer, you earn less than a maid in Kuwait'

- Eline

Two months after her return, she tells me on Facebook she has moved to Madagascar's third city, Antsirabe: "Next month, I will build my own house and maybe next school year, I will start a training, so I can teach in a pre-school."

Eline knew about the stories of domestic workers being treated badly in Arab countries before she left to work in the Middle East; yet she and other women continue to take the risk to escape poverty.

"There is little work [here]," says Eline, "and even if you have a job as a teacher or a police officer, you earn less than a maid in Kuwait."

But after all she has been through, her advice for those tempted to go and work in the Gulf is clear: "Don't go, life is hard there, but anyway the choice is yours."

Additional reporting by Fabienne Rafidiharinirina in Madagascar.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.