Medieval robots: How al-Jazari's mechanical marvels have been resurrected in Istanbul

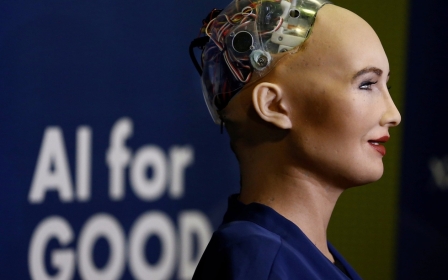

Today, robots are everywhere. We even worry about them taking our jobs.

But the history of automation goes back some 900 years, when Ismail al-Jazari, a Muslim scholar, invented the first robotics, water clocks and other mechanical devices.

In order to inspire new generations in Turkey and the rest of the world, his outstanding machines have now been recreated for The Magnificent Machines of al-Jazari, an exhibition at the UNIQ Expo in Istanbul.

Badi al-Zaman Abu al-Izz Ismail ibn al-Razzaz al-Jazari - known as Ismail al-Jazari for short - was a Muslim scholar and polymath born in 1136 in Diyarbakır, Anatolia, in what is now modern Turkey. He served as a royal engineer at the Artuqid Palace during the 12th century at a time known as the "Islamic Golden Age".

He is widely revered for his masterwork, The Book of Knowledge of Ingenious Mechanical Devices, which he wrote at the request of Nasiruddin Mahmud, the Artuqid sultan.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

In his book, al-Jazari explained the construction of his devices and automata, from water-raising machines to fountains, complete with illustrations and instructions that gave engineers the opportunity to reuse them.

Mehmed Ali Caliskan, the founder and general manager of the project to reconstruct the medieval robotics, is himself an engineer.

"We think that if we can revitalise his fabulous world, combining mechanics, science, art and philosophy, this would inspire a lot of people like us," he says.

"Our biggest motivation was to carry this inspiration to the masses."

Caliskan is the son of Durmus Caliskan, a mechanical engineer, who compiled al-Jazari's sketches for his 2015 book The Magnificent Machines of al-Jazari, the most detailed account of the medieval genius in Turkish.

His dream was to put all the machines and devices into a "museum of al-Jazari". A year after his father's death, Mehmed Ali Caliskan and his brother made his dreams come true.

"The exhibition is the first step toward my father’s dream of a museum," Caliskan explains. "The technical background of the exhibition is based upon my father's 15 years of effort."

Still inspiring today's engineers

But why are al-Jazari's inventions so important for today's generation?

The road to modern machinery, academicians and engineers say, starts with the work done by al-Jazari 800 years ago.

"The impact of al-Jazari's inventions is still felt in modern contemporary mechanical engineering," wrote 20th-century English engineer and historian Donald Hill in his book Studies in Medieval Islamic Technology.

Jim al-Khalili, professor of physics at the University of Surrey, says: "Al-Jazari should inspire today's engineers and, even more so, the young engineers of the future: schoolchildren who are thinking of engineering as a career. [But] I feel he is not as well known as he should be, not even in Turkey or the Arab world."

Mustafa Kacar, professor at the Department of History of Science at Fatih Sultan Mehmet University in Istanbul, told MEE that al-Jazari's inventions were the prototypes for many of the technological tools that we use daily.

"Take four-stroke engines for example," he says, "or gear wheels, crankshafts, pneumatic and hydraulic systems, music boxes, automats and control systems; these are all the technological innovations that have been developed by him."

Kacar also emphasises how al-Jazari's book, The Book of Knowledge of Ingenious Mechanical Devices, was the most important work of engineering written before the Renaissance centuries later.

"The idea of having robots to do humans work - or simply automation - was developed by al-Jazari 250 years before Leonardo Da Vinci, with some excellent examples."

The end to the Muslim world's 'golden age'

During the Islamic Golden Age, which ran from the eighth century to the 14th, many scholars and polymaths from the Islamic world made significant contributions to a range of scientific areas, including astronomy, mathematics, medicine and geography. Their inventions, scholars say, paved the way for Europe's later Renaissance and Enlightenment.

For instance, al-Biruni, a Muslim astronomer, mathematician and geographer, was born in 973 in what today is Uzbekistan. He measured the circumference of the Earth, producing what was the most accurate calculation made during the Middle Ages.

Ibn Sina, better known in the West as Avicenna, was a Muslim physician and philosopher, born in 980 in Bukhara (modern day Uzbekistan).

Described by many as "the father of modern medicine," he wrote the Canons of Medicine, which was used as a medical textbook in European universities until the 17th century.

But in the 21st century Muslim countries see relatively less scientific activity. According to the World Bank, in 2016 the United States and the European Union respectively published 426,165 and 613,774 articles in scientific and technical journals.

That compares to 40,974 in Iran and 33,902 in Turkey, although the number of articles is rising.

The main reason for this, according to Professor Jim al-Khalili, is that the once mighty Islamic empire began to fragment and lose its wealth and influence by the 13th to 15th centuries.

"Many factions appeared and were more interested in protecting their borders and their interests than in scholarship and learning," al-Khalili explains to MEE.

He also highlights that learning and knowledge flourish wherever there is wealth. In addition, the introduction of the printing press in the 15th century helped Europe move ahead quickly.

"During the Renaissance, Europe suddenly became very wealthy, for example discovering the New World, and a scientific revolution took place thanks to men such as Copernicus, Galileo and Newton, leaving the Muslim world far behind."

But given that civilisations rise and fall naturally, he says, "in the Islamic world, particularly in countries such as Turkey, there is no reason why there should not be a renaissance now."

In order to inspire new generations of scientists in Turkey and the rest of the Muslim world, The Magnificent Machines of al-Jazari will remain open till mid-June.

"We will then travel to different parts of Turkey and even the world," says Caliskan, "We will also turn the exhibition into a museum in three to five years."

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.