Moon Knight versus Ms Marvel: What lies beyond representation?

“Are you an Egyptian superhero ?” A teenaged girl asks the gold-draped, thirty-something woman swooshing down to rescue a bus full of clueless bystanders. “I am,” she responds nonchalantly, driving the audience into a frenzy.

This was the moment Arabs and Egyptians have been waiting for: the moment an Arab superhero – the biggest honour in contemporary pop culture – was born. The moment a people who have been stigmatised on screen for decades finally had their moment in the sun.

It’s a purely symbolic moment of course, and perhaps puerile in essence. The fact that a woman in a silly costume kicking ass would be cause for celebration is a testament to how reductive global mainstream culture has become.

But art, progressive politics, and intellectualism can take a backseat here. It’s all about the non-white woman with a cape and cool wings saving lives with her physical powers, and in doing so, reflecting all of the young Arab women craving to see someone who looks like them on the world’s biggest stage: American TV.

The aforementioned scene is a rare highlight in Moon Knight, the much-hyped, Egyptian-flavoured Marvel series directed by Mohamed Diab – the first Egyptian filmmaker to head-up a Marvel project in Hollywood.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Plenty have raved about Moon Knight and praised Oscar Isaac’s powerhouse performance, the incorporation of Egyptian mythology into the Marvel universe, the refreshing depiction of contemporary Cairo, and, most of all, the inclusion of Egyptian and Arab pop tunes.

Moon Knight was initially intended as a one-off, an atypical superhero story made distinctive by the cultural input of its Egyptian heroine.

But then came Ms Marvel to fully expose Moon Knight’s shortcomings and prove that Diab’s admittedly admirable work in fact follows a successful, though commonplace, woke template.

The very first Muslim superhero from South Asia to grace the American screen, Ms Marvel mixes a Pakistani myth related to the 1947 partition of India, with Indian tunes and copious insider references to Bollywood and Muslim traditions in a manner that feel more seamless and freewheeling than the often stodgy Moon Knight.

Moon Knight's creative overreach

While Moon Knight is weighed down by the legacy and rich history of ancient Egyptian lore and struggles to do justice to it, Ms Marvel, achieves the modest target it sets out for itself with notable aplomb, proving once again that stories with core emotional honesty can transcend formula.

The narrative of Moon Knight is more ambitious, and more adult-oriented than Ms Marvel.

Isaac is Marc Spector, a fearless mercenary with a dissociative identity disorder who has conjured up an alter ego in the shape of the Englishman Steven Grant, a shy yet lovable ancient Egypt-obsessed museum clerk.

But, it is soon revealed that Marc is actually the avatar of the pharaonic moon god Khonshu. He is married to Layla El-Faouly (May Calamawy of Ramy fame), the Egyptian daughter of an archaeologist who was mysteriously killed in an expedition.

Marc/Steven embarks on a treacherous journey to stop cult leader Arthur Harrow (a disinterested Ethan Hawke in one of his worst screen performances) from resurrecting Ammit, the Egyptian goddess of justice who judges people on the hazy "nature of their hearts" and not their actions - whatever that means.

Ammit and her servant Harrow plan to rid the world of everyone with an impure heart, including children.

There are grand summits for the gods and their avatars; rooftop chases and street fights in the bustling alleyways of Cairo; Matrix-style distortion of various unreliable realities (a theme Diab explored before in his 2014 penned-indie Decor) and predictably, psychoanalysis explaining why Marc was forced to invent Steven.

The main problem with Moon Knight is that it tries to be too many things all at once and fails at nearly all of them. On one hand, this is an Indiana Jones-type adventure. On another, it’s a cartoonish introduction to the under-explored world of Egyptian mythology. But in its attempt to make the subject more relatable, the show miserably founders.

Moon Knight is also a study of trauma and domestic violence; and last but not least, a half-baked treatise on free will versus predestination.

This hodgepodge of underdeveloped themes is augmented by run-of-the-mill action sequences that not only lack invention but also emotional thrust.

Diab, a competent action director above all, attempts to inject the rather stale action with some vibrancy by using Marc/Steven’s blackouts to jump forward to the bloody aftermath of violence.

It’s the sole imaginative facet in a series that otherwise prioritises pointless and extensive exposition of both Egyptian mythology and the protagonist’s troubled backstory.

The best combat action in film, be it Bruce Lee or the classic Wuxia pictures of King Hu from the ‘60s and ‘70s, is a refraction of the power and magic of cinema: the ballet-like poetry of moving bodies creating harmony out of chaos. Moon Knight, by comparison, is another example of the Marvel visual ethos: repetitive spectacles choreographed on autopilot.

Egyptian influences

Diab’s biggest contribution is the vibrant Egyptian-leaning soundtrack. Much ink has been spilled over the use of music – from the Mahragant tune El Melouk and Abdel Halim Hafez’s swing-tinted Shaghaloony to the heady remixes of Arab classic Saat Saat by Sabah and Batwanes Beek by Warda.

While it's hard to know what an unaware western viewer makes of these musical cues, for the Arab viewer the impact is incredibly powerful.

Far more significant than the sight of an Egyptian woman superhero, the evocative use of these adored tunes is a testament to the capacious appeal of a rich music catalogue, of a singular Arab art form, that is yet to be discovered by the Western world. Music, and art, are what form worthwhile national legacies, not superheroes.

Equally praiseworthy is Diab’s interpretation of Cairo, which was actually shot in Hungary due to Egypt’s notoriously stifling bureaucracy. It's a world away from the offensively exotic desert of Wonder Woman 1984 and Diab’s Cairo is the buzzing, unruly mess denizens of the Egyptian capital simultaneously love and abhor.

Teeming with eternally moving tuktuks, watermelon carts, falafel nooks, and the never-ending commotion of people, Diab, who assembled a mini-crew of Egyptians, captures the congested ambiance of Cairo life with affection and genuineness, offering a glance of a city that is equal parts quaint yet suffocating.

Beyond 'Muslim-ness'

The New Jersey-set Ms Marvel is a radically different beast. A coming-of-age story echoing Spider-Man and Kick-Ass, Pakistani-Canadian newcomer Iman Vellani is Kamala Khan, a second-generation American-Pakistani vlogger with an unhealthy fixation on the Avengers and Captain Marvel.

Heavily involved with her Pakistani and mosque community, she nonetheless strives to break free from the clutches of her overprotective but endearing parents.

A bust-up with her parents forces her to sneak out to attend an Avengers comic-con, donning her beloved Captain Marvel outfit adorned with an old bangle belonging to her great-grandmother Aisha.

The glowing bangle turns out to hold magical powers that give its bearer the ability to shoot up objects similar to Spiderman. It is soon revealed that the bracelet is sought after by a group of djinns to who Aisha once belonged.

The group has been exiled from a dimension called Noor (light) during the partition and only the bangle can help them go back. Violent confrontations ensue as the Department of Damage Control (DODC) goes on their trail.

Unlike Moon Knight, politics are front and centre in Ms Marvel. Partition is at the heart of its supernatural mythology, which itself gradually transpires into an allegory on the consequences of the British-enforced separation between India and Pakistan.

The DODC represents the unabashedly xenophobic western governments whose sweeping powers shield them from being held accountable for racism.

Gender politics also figures heavily through the veiled Nakia (Yasmeen Fletcher), Kamala’s closest friend and mosque buddy who embodies both the cultural discordance of adolescent Muslim-Americans and the struggle of young women for self-determination.

Although mostly quaint in tone, Ms Marvel is unafraid to take some swipes at Islamic norms, or more accurately the Islamic norms practiced by Kamala’s Pakistani community.

Nakia openly criticises the relegation of women to the back of her place of worship during sermons and her feminist battle to shake things up in the mosque hierarchy evolves into an intriguing subplot.

The relative freedom given to her older, pious brother Aamir (Saagar Shaikh) hints at the lingering double standards governing the upbringing of girls and boys in Pakistani communities.

There's also Kamala’s mother, who confesses in one scene that the America they encountered was not the America of their lofty imagination and that the "American dream" turned out to be nothing more than a myth.

But Ms Marvel’s biggest achievement is in its representation of Muslim traditions. From the use of everyday vocabulary to the exploration of mosque life, the makers of the series – the majority of whom are Muslim or from Muslim and Middle Eastern backgrounds – have astutely excised the alienating foreignness of Hollywood’s stereotypical treatment of Muslim life.

The marriage of Islamic customs with South Asian cultural heritage – the music, the clothes, the dancing – is all the more remarkable in how it illustrates that Muslim lives are nowhere as uniform as western film and TV habitually makes them out to be.

It’s all surface-level examination – this is Marvel after all - but there’s irrefutable joy in seeing Muslim characters grappling with dilemmas unrelated to their belief systems.

Like real life, religion is one aspect of these teenage lives. And although it is irritatingly overemphasised in some sequences, it’s never cast as the main force or sole philosophy informing their behaviour.

These myriad layers, weaved with deft seamlessness, come to life in a charming if occasionally saccharine palette that draws parallels between Marvel’s colourful comic look and flamboyant Bollywood chromatics.

Philosophy and the world of superheroes

Ms Marvel does so much within the limited parameters it operates under; Moon Knight, by comparison, is a lost opportunity, especially in its management of ancient Egyptian history.

Devoid of any politics – surprising given the overly political nature of Diab’s work (Clash, Amira) – the show’s Egyptian mythology comes off as merely a pretext for the story’s action.

Egyptian civilisation has inspired the world in various domains – art, architecture, sciences, and religion. Philosophy, however, is one realm ancient Egypt had little impact on. Until recently in the West, ancient Egypt has been thought not to have possessed any tangible philosophy, with the history of thought deemed to have started with the Greeks.

Only recently has it been discovered that various pre-Socratic philosophers such as Xenophanes, Parmenides, and Heraclitus were potentially influenced by ancient Egyptian thought, which set up the fundamental basis for their reflections.

Moon Knight does not bother to relay such under-explored Egyptian wisdom. Like the average Hollywood film, Egyptian gods are cast as mindless action figures carrying an infantile view of humanity. The show is no different than Clash of the Titans, which dressed up Greek mythology in the same inane and hollow fashion.

Superheroes have often been compared to Greek mythology – an erroneous, superficial theory that has been refuted time and time again. Superman, and the first wave of superheroes, emerged in the late '30s during the run-up to the Second World War and the rise of Nazism.

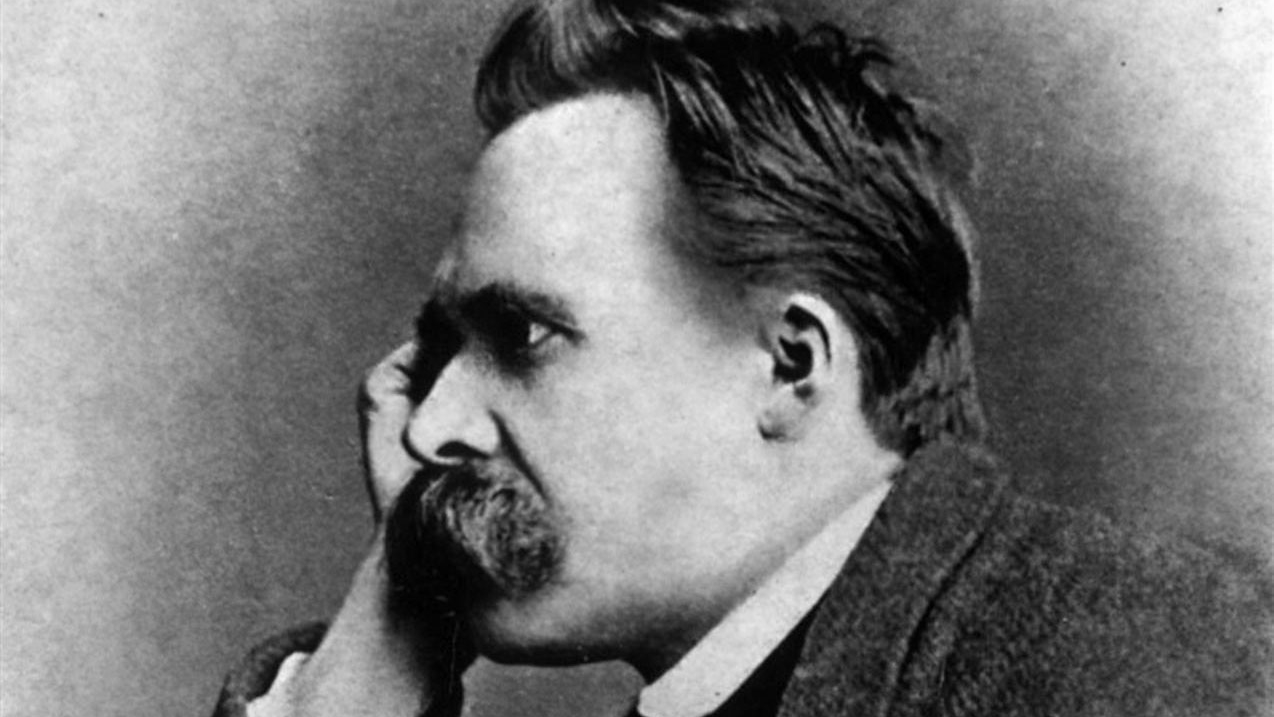

These characters developed amid the spread of the philosophy of Friedrich Nietzsche, who coined the term “superman” in response to the “death of God”; the idea that God no longer formed the locus of purpose for western societies and that alternatives must be found within man himself.

The German philosopher's "superman" reverberated amid an audience of creatives confronting the nihilistic destruction of two world wars and the seeming inaccessibility of justice when it came to the atrocities they brought about.

Their answer was to create new gods: spotless beings with perfect physical prowess that would fill in the gap in the absence of divine justice. With time, our superheroes grew more complex, more ethically conflicted and each character and storyline would reflect the mood of the time.

Unlike Christopher Nolan’s Batman trilogy – an epic by-product of the moral ambiguity of the George W Bush era – the post-millennial Marvel superheroes say little about their time.

The sole engagement they have with the politics of the present is in the rise of identity politics that have forced western cinema to adopt gender and racial diversity on and off-screen.

Moon Knight and Ms Marvel are examples of this and they wouldn't exist without the colossal commercial success of Black Panther and Shang-Chi.

Only Ms Marvel and Black Panther have offered a glimpse of the ample rewards when identity politics are inserted into the equation. Fascinatingly though, only Ms Marvel tackles the long-ignored elephant in the room: the question of God.

Modern-day superheroes were designed to be the alternative to the traditional notion of God: they’re humanly flawed, more self-sacrificing, and far more attentive. Religion or God did not figure traditionally in most Marvel and DC pictures because God no longer had a place in these self-autonomous universes.

By making Kamala a potential descendent of djinns, supernatural beings of Islamic lore, Ms Marvel brings religion into the story in a way that lends it more mystery and, surprisingly, more warmth, if not exactly depth.

By contrast, Moon Knight's Egyptian gods are no different from their Greek counterparts that Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle challenged: they’re self-centred, brutish, and unwise.

The wisdom and beauty of pharaonic thought are nowhere to be seen in these gods; their rigid conception of good and evil, of inalienable destiny, has no relevance in a world of ethical greyness.

The choice between good and evil has always been the central theme of the Marvel stories. The role of God in Ms Marvel is still unclear, but the series-makers have at least adopted a palpable position that leaves room for debate and progress.

As such, one can’t help but ponder the function of the Moon Knight gods beyond the presumed maintenance of harmony in the universe, and the question of what kind of relationship humans could have with these deeply defective deities remains unresolved.

And let’s not even get into the shoddily-drawn Descartes-inspired levels of reality that has little to nothing to do with the main themes of the story.

Many of Moon Knight’s pitfalls might have been somewhat overlooked had Ms Marvel not arrived so shortly on its heel. The latter does not reinvent the wheel, containing little of the confidence and none of the muscular filmmaking of Black Panther, but it does pack a lot of ideas when compared to the average Marvel outing.

Its importance in celebrating Muslim culture on Disney+, one of the planet’s most-watched platforms, is an act of immense political gravity.

Moon Knight may be well-intentioned, but its achievements are comparatively inferior to Ms Marvel.

It’s a show that could work if you manage to oversee its copious faults. For the thinking, inquisitive viewer though, Mohamed Diab’s first foray into Hollywood increasingly feels like a giant folly with a lot of promise and too little reward.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.