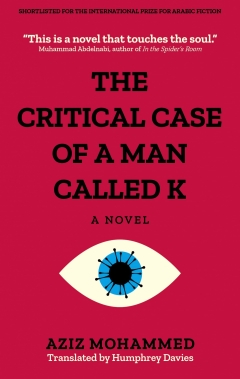

The Critical Case of a Man Called K: Saudi author's debut tackles illness and transformation

Much as Kafka’s young Gregor Samsa woke one morning to find he was an insect, Aziz Mohammed’s young narrator wakes to find his nose is bleeding, a first sign of his leukaemia. The Critical Case of a Man Called K, the Saudi author’s first novel, is in some ways a re-telling of Kafka’s The Metamorphosis, through the lens of the changes happening to a critically ill body.

The novel takes the form of a 40-week journal, written first on the narrator’s work laptop, then at home and in the hospital. The unnamed narrator borrows his moniker “K” from Kafka’s The Castle and quotes extensively from Kafka’s Diaries. Like the Diaries, this is a first-person account. But The Metamorphosis is also central, and K might as well have turned into a giant bug. His family treats his new body, transformed by leukaemia, as no less terrifying and unwelcome than a human-sized cockroach.

Before publishing The Critical Case of a Man Called K in the original Arabic in 2017, Mohammed had published only one short story, and that was under a pseudonym. But the novel found a passionate fandom even before it was shortlisted for the 2018 International Prize for Arabic Fiction (IPAF). Slowly, it is appearing in other languages. It came out in Simon Corthay’s French translation in January, Humphrey Davies’s English translation this month, and is forthcoming in Chinese.

It is not only Kafka that shapes the protagonist’s story. Later in the book, the narrator professes an affection for Jeff Kinney’s Diary of a Wimpy Kid, and his tone throughout the book reflects that series’ cynical, boyish sarcasm. This comes through at just the right pitch in Davies’s translation, which is as unassuming as it is tightly paced.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

The narrative rushes from week to week with a barely suppressed hysteria as leukaemia rapidly transforms K’s body and relationships, as though we were tumbling down a rabbit hole of illness and screaming silently to ourselves the whole way.

A patchwork of stories

Mohammed’s debut is not only about illness, but also about the ways in which we make ourselves out of stories. In the opening chapters, K has to attend a meeting focused on corporate success stories, and some of his co-workers model their self-image on this genre. K, on the other hand, models his after foreign novels. He begins writing his story on a computer at work, where he is in the IT department in an unnamed city. He writes: “Let’s call it the Eastern Petrochemicals Company, after the Eastern Petroleum Company where one of [Jun'ichiro] Tanizaki’s protagonists works.”

In flashbacks to K’s childhood, we learn that he has never been entirely healthy. His boyhood trips to the doctor resulted in mockery from the medic and scorn from his father. His father frequently told him, in response to health complaints, “Don’t exaggerate!” Thus, he forces himself not to see what’s going on in his body until he collapses. When he is taken to the hospital, blood tests show something is very wrong.

All of these minor characters seem to be hurtling towards some terrible future, such that even the inanimate objects are filled with dread

The doctor directs K to the capital for further testing. He takes an excruciating train journey, every moment of which is dense with his alienation and dread. He watches a woman who is travelling with her children and an anxious foreign maid, and an elderly African couple, where the husband is ill.

All of these minor characters seem to be hurtling towards some terrible future, such that even the inanimate objects are filled with dread. The elderly couple’s “suitcases also seemed to be trying to hang on, though with great effort, so that it seemed that at any moment they might fall apart, scattering their contents”.

Fittingly, K begins Thomas Mann’s Magic Mountain on the train journey, although he never finishes this classic novel about illness and death. That unfinished novel hangs over the narrative like a thread halfway unspooled, a treatment not completed.

Later, the company’s insipid “success stories” are echoed by the equally insipid “cancer-survivor stories” with which K is deluged. As K writes, “It would have been insensitive of anybody to come and tell me tales of patients who’d lost the battle and died horrible deaths, but it would have been more entertaining.”

The social demands of illness

Like the Samsa family in The Metamorphosis, K’s family goes through periods of being angry, disappointed, afraid, and ashamed of his illness. K’s older sister is the most powerful among them, the one most interested in burnishing the family’s reputation. The echo of her high heels clicking through the family home is one of the book’s most terrifying sounds. She has already married into a more powerful family, and she is determined to make a good match for K’s brother.

This match, she has decided, must not be derailed by K’s illness. As K drolly reflects, “It was miraculous enough that those people had agreed to marry their daughter to my hardworking brother and his unconnected family, and any mistake from our side might cause a rift that could never be mended.”

K’s social obligations create the most painful moments in the book. Now that he’s ill, the family insists even more vigorously that he participate in family functions. And although K wants to stop caring, he is always drawn back in. He avoids the contract-signing for his brother’s wedding, but he gives in to pressure to visit the bride’s family.

Here as elsewhere, K is keenly attentive to the menace of the objects around him. In the bride’s family home, “Most conspicuous were the ancient swords and rifles they had hung on the walls, to proclaim that riches hadn’t caused them to forget their heritage and their forefathers’ way of life, as though, despite all the conspicuous wealth, they’d prefer to live warring with a neighbouring tribe over a water well.”

The group sits down to an enormous meal. K is suffering from such acute nausea he can’t bear food, but, after much nudging, he gives in and eats. Later, he vomits so violently that he passes out, and the bride’s family must break down their own bathroom door. They continue to harangue K by visiting him in the hospital, proud and proprietary after they’ve “rescued” him from death. The reader can only grit their teeth as these men sit around his hospital room, talking to each other when K remains stubbornly sunk in silence.

The men of the bride’s family, like nearly all the book’s characters, are caricatures. It is rare for a person in the book to be given dimension, and the only figures K can really connect to are other patients in the hospital. And, soon after we come to care about them, they die.

Better off dead

Much as Gregor’s family wants him to leave in The Metamorphosis, K’s family also says, in their most heated arguments, that K should hurry up and die. Some, like K’s mother, are concerned about his physical suffering. K’s sister, on the other hand, “begged me to die quickly and rid them of all the trouble I was causing”.

The novel is a fast and enjoyable read, grounded in the capitalist nightmare of 21st century healthcare

K’s death hangs over the novel, seeming to grow closer and closer as we speed toward the final pages. But The Critical Case of K does not end like The Metamorphosis. Neither does it give in to the tropes of “survival” or “success”. K reaches the final stage of his personal metamorphosis at 40 weeks, much like a baby’s gestation, and the change that happens is unexpected.

We never find out what happens after the 40th week, or how this memoir has reached our hands. Perhaps a figure like Kafka’s friend Max Brod rescued the pages from deletion, or perhaps the narrator himself decided to overcome his fears and publish them.

Regardless, the novel is a fast and enjoyable read, managing to thread a narrative needle between the sardonic youthfulness of the Diary of a Wimpy Kid stories and the dispassionate alienation of The Metamorphosis, all while keeping it grounded in the capitalist nightmare of 21st-century healthcare.

In a 2018 interview with IPAF organisers, Aziz Mohammed suggested that his next novel might be connected to this one, adding, “The temptation to go further with something I thought I was done with is usually what motivates me to continue.”

We can only wait impatiently for whatever is to come next.

The Critical Case of a Man Called K is available from Hoopoe Press, translated by Humphrey Davies

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.