9/11 attacks: Why Netflix's Turning Point documentary is a let-down

On 1 September, a week and a half before the 20th anniversary of the 9/11 attacks, Netflix released the documentary series Turning Point: 9/11 and the War on Terror.

Directed by the award-winning filmmaker Brian Knappenberger, the series tells the story of the heinous attacks and the subsequent US-led "war on terror", which, despite the recent US withdrawal from Afghanistan, continues to this day.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Ahead of the release, Knappenberger, whose previous works include We Are Legion, a film about the Anonymous hacktivist collective, and The Internet's Own Boy: The Story of Aaron Swartz, said he wanted to understand the way in which the attacks transformed the American psyche.

“Now, as US troops are leaving on the 20th anniversary, this is the moment to take a deep breath, step back and ask in the most honest possible way: how did that day change us?” he said.

He added that having travelled to Afghanistan as a young filmmaker a year after the events, he could not have anticipated the war lasting 20 years.

That inability to foresee is not for lack of access to some of the most pivotal players in the conflict. The film boasts an enviable cast of talking heads, including former warlords, Taliban leaders, former CIA officers and White House officials.

Combined with accounts from survivors and US soldiers who fought in the war, the series purports to offer “illuminating perspectives and personal stories of how the catastrophic events of that day changed the course of the nation”, as well as the high cost of the aftermath.

Nevertheless, big names do not make up for failures. Despite the attempts to incorporate different voices, and explore some of the more uncomfortable scenarios surrounding the attacks, the series sidesteps the tough questions, depends too much on the Washington elite to explain away their failures and resorts to stereotypes and caricatures to keep viewers interested.

Here are three reasons why Turning Point: 9/11 and the War on Terror is such a disappointment:

Centring American trauma

The events of 11 September 2001 were immensely traumatic, with nearly 3,000 people killed in the series of attacks that took place on that ill-fated Tuesday.

Many of these victims were ordinary Americans, on the hijacked planes or working in the Twin Towers of the World Trade Center. They were also firemen, paramedics, police officers - who are known in the US as “first responders”.

For days and weeks, mothers and fathers looked for their missing daughters, sons, brothers and partners. Downtown Manhattan was caked in the ashes of the towers, and plumes of smoke rose from the charred skeletons of fallen buildings long after the dust had settled.

As legitimate as the horror felt by ordinary Americans was, the series contains a disproportionate focus on the pain of Americans, often reconstructing their fears, biases and ignorance without questioning them. This occurs almost entirely to the exclusion of later victims of the American response to the attacks.

The 9/11 attacks did, after all, take place on a single day. The ensuing wars under the rubric of the "War on terror" were a life-defining series of events that have lasted 20 years, cost the lives of close to a million people, and led to the displacement of 37 million people across the globe.

While the series touches on the skulduggery of Washington elites as they sought revenge and the hawkish power plays that led to and followed the invasion of Iraq, at its core it is still a story of American failure and American pain. The victims of the post-9/11 wars have almost always been people who are not American, but Knappenberger and his team are simply unable to move their gaze beyond American trauma.

As the title of the series makes clear, for the filmmakers 9/11 serves as a point of inflection, ie the turning point in history. Even if there is an attempt to present a historical context, US actions that fed anger towards it are largely minimised.

We are fed the impression that all of this anger is driven by US presence in the so-called Muslim world. There is little attempt to explain what motivates this obsession with intervening in these countries, or what the presence means materially and politically for the people living there; a line of inquiry which may have forced the film’s producers into a more unpalatable introspection. The discontent felt by members of al-Qaeda towards America, or for that matter the expansion of the American empire, involving destabilising governments or invading nations, provide little more than academic B-roll.

Planting ‘seeds of doubt’ on abuses

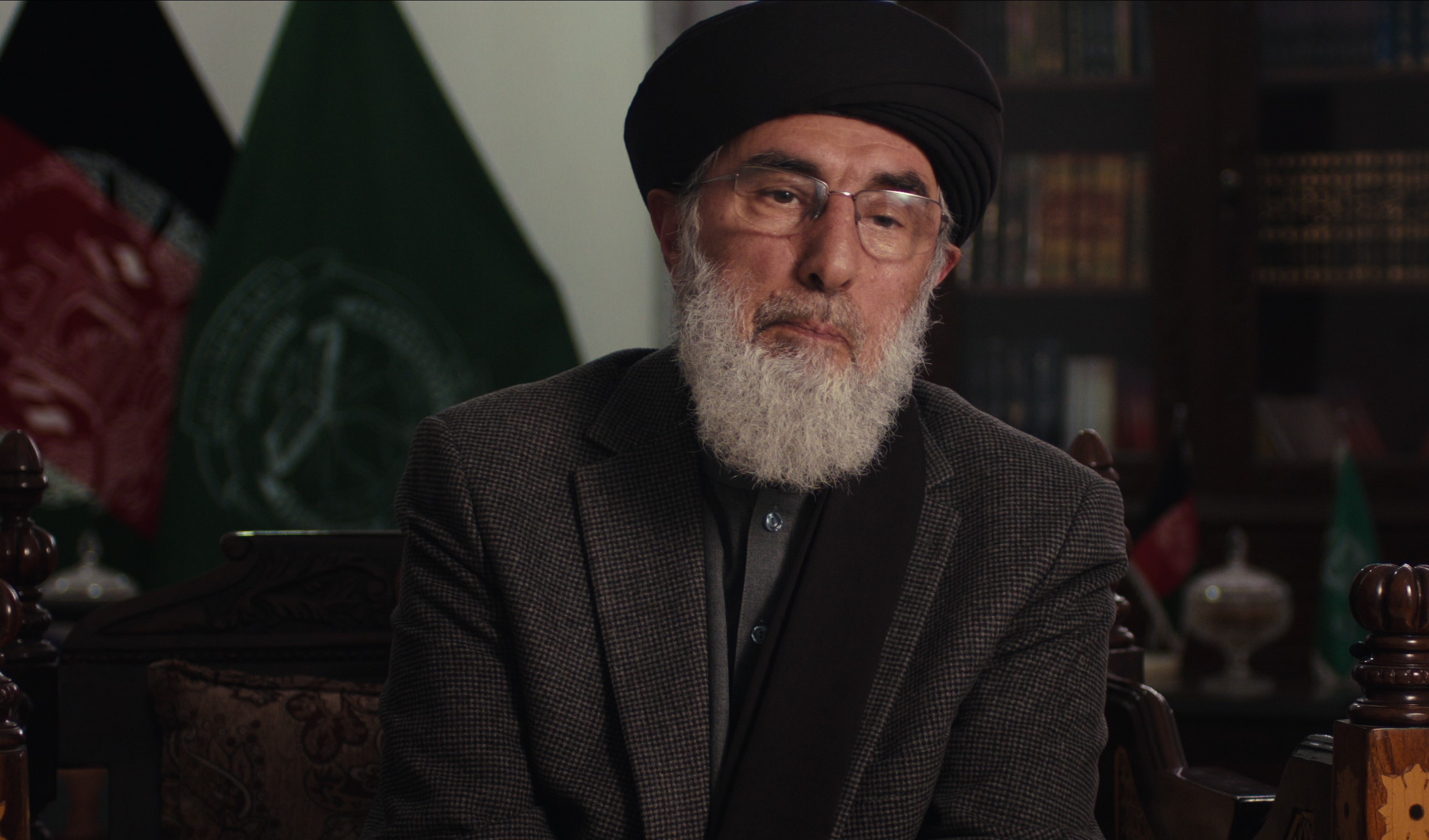

Although the series presents a wide variety of interviewees, from former mujahidin leader Gulbuddin Hekmatyar, to US lawmaker Barbara Lee, to Pakistani politician Hina Rabbani Khar, the predominant voices are US government advisers, former officials from the FBI and the CIA, and political leaders from Afghanistan, with a sprinkling of journalists and human rights activists thrown in.

The story is driven by the voices and perspectives of its subjects, without a narrator, the documentary provides a definitive guide to the events of 9/11 but an ambiguous, complicated account of the "War on terror".

Any claim the film might have on a balanced reading of the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq is undermined by the platforming of some of the biggest proponents of those invasions, including the likes of David Petraeus, former director of the CIA, and General John R Allen, former leader of US and Nato troops in Afghanistan. They are presented in the same talking-head manner as victims of the attacks and academics: it's an approach that gives them an unjustified air of impartiality, and detaches them from their authorship of the failures and abuses carried out under their command.

Where the documentary had ample opportunity to drive home the reality of the immense moral and political failure of the "War on terror", it focuses instead on a series of "poor decisions" that led to America losing those wars

Their inclusions are startling, given these men have always had a vested interest in furthering a specific narrative about these wars - one that remains largely the same as when they were fighting in them. Why we should hear from them now without the caveat of their failings, or better still trust their "expertise", is unclear.

While the series makes an immense effort to educate the audience on how the American government under George W Bush appeared to instrumentalise US trauma, misappropriate law to expand its powers, surveil citizens at home and wage endless wars abroad, it still offers proponents of those policies enough space to plant seeds of doubt on matters where there should really be no argument.

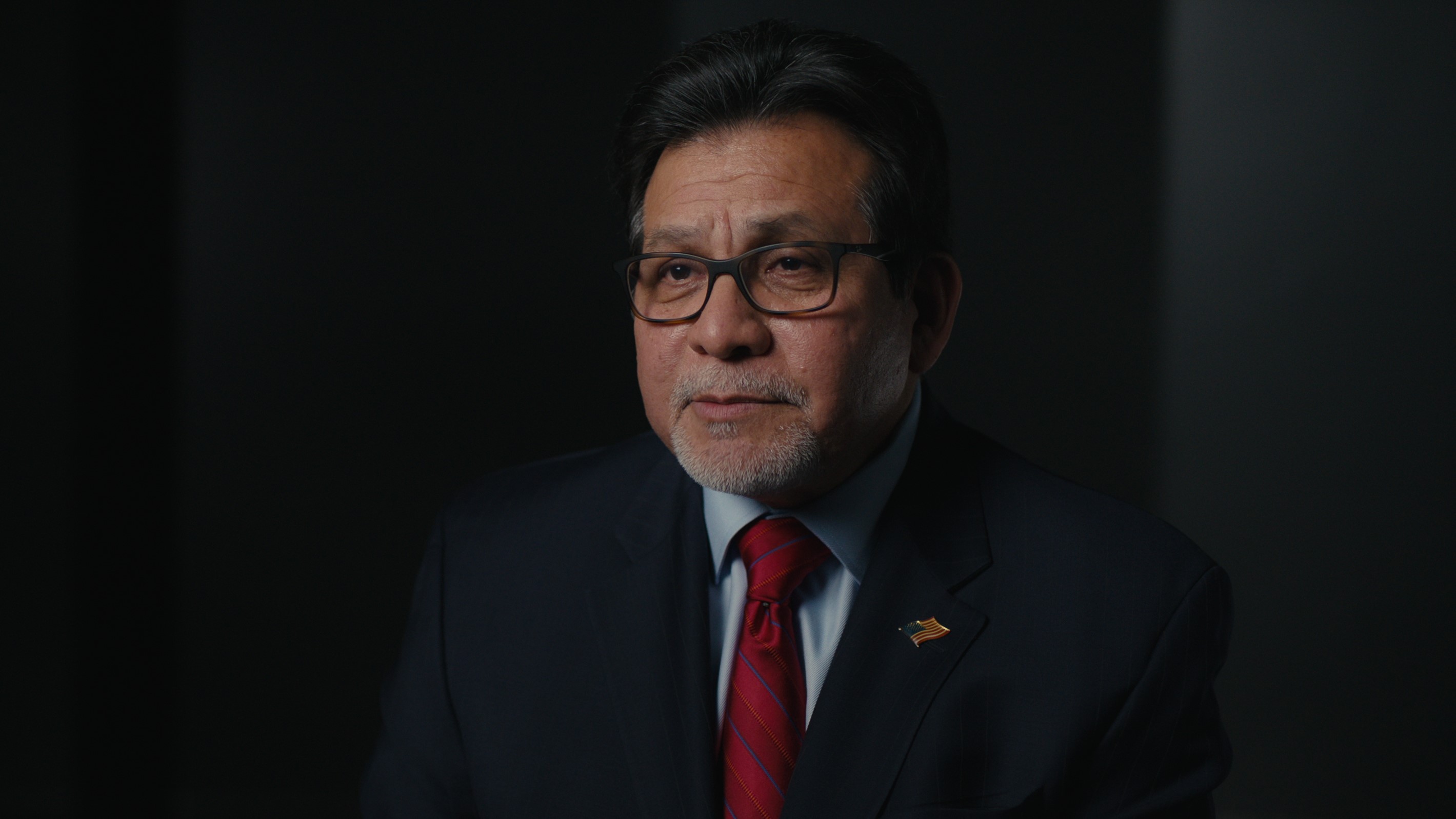

On the question of torture and abuse at CIA blacksites or at Guantanamo Bay, which the US was repeatedly said to be practising, Alberto Gonzales, former White House counsel for George W Bush, says in episode three: “We went back and looked at the convention against torture, which was the genesis of the Anti-Torture statute… The head of the Criminal Division of the Department of Justice wrote that torture is that activity of which the very mention sends shivers up one’s spine, such as needles under fingernails, such as piercing of your eyeball, such as electric shocks to your genitals. We weren’t anywhere close to that.”

A very clear idea of torture as the use of mental and physical harm to extract information from, or to punish, a victim is therefore reduced to the subjective experience of "sending shivers up one’s spine" by a member of the very administration accused of engaging in such abuses.

The focus and reliance on the recollection of government officials’ decisions, rather than focusing primarily on a wider variety of activists, journalists and Afghan scholars about the impact of these decisions, is really an exercise in hubris.

Furthermore, voices likely to offer critical perspectives, and who do make the cut, are simply not given equal platform. When Pardiss Kebriaei from the Centre for Constitutional Rights and Zahra Billoo from the Council on American-Islamic Relations are interviewed about the rights of Guantanamo “detainees”, or about the surveillance of Muslim Americans, their testimony and insight are not given the same space to counter the project of the "War on terror" itself that officials like Gonzales are given to defend it.

Where the documentary had ample opportunity to drive home the reality of the immense moral and political failure of those wars, it focuses instead on a series of “poor decisions” that led to America losing them, abandoning its stated goal to "civilise" the region and therefore losing its stature, or compromising the idea of the “promise of America”.

Crucially, the US military does not come under adequate scrutiny as an institution. The insights of some are buried so deep within the film, and left unexamined, that they feel like disconnected afterthoughts, such as those of Brittany Ramos DeBarros, a former US army captain who says her experience in Afghanistan taught her that “you can’t take an institution that’s designed for violence and use it to build up healthy and safe communities”. And Jason Wright, the former military defence counsel for the alleged 9/11 mastermind Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, who says that “the policy of the US government was clearly not to pursue a fair trial for anyone”.

By episode four, the series feels like a liberal lament at the loss of American power and the moral high ground that the gruesome events of 9/11 had gifted the country’s military-industrial complex. The boons enjoyed by America’s armed industry remain completely neglected by the filmmakers, too.

Nowhere in the five hour-long series is the question about whether the architects of America’s "War on terror" ought to be held to account. Instead, as the film approaches the final credits, a piano rendition of America the Beautiful plays to a collage of images of war.

Muslims are still meant to be feared

Like US President Joe Biden’s speech after Taliban took over the Afghan capital in August, the series is unable to avoid the same orientalist, racist and civilisationalist rationale in its depiction of 9/11 and subsequent "War on terror".

The opening credits to the show, for instance, begin with the image of a Muslim woman in a burqa with a gun in hand. The leaders of al-Qaeda are introduced, with mugshots and ominous background music, as if gory villains in a Quentin Tarantino film. These villains were once aided by America, but they are monsters who have overstayed their use. They have no other complexity. “We failed to understand and to comprehend the power of religion,” Bruce Hoffman, senior fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations, says in episode one.

In so doing, the two-dimensional depiction of the 9/11 hijackers and al-Qaeda fighters serves only to underwrite and reinforce the pop-culture depictions of Muslim villainy that have filled our screens on cable news and Hollywood over the past 20 years. We don’t find out anything new about these al-Qaeda operatives. Neither does the film seem particularly concerned to pose new questions.

The series also erases the impact America’s wars have had on Muslim-Americans, including how counter-insurgency operations aimed to remould the way Muslims practise their religion, think or talk in matters concerning the American empire.

Since the attacks, Muslims in the US have faced intense scrutiny at airports, FBI infiltration of their communities and mosques in the hunt for supposed terror cells, and discriminatory laws controlling their entry into the country. Further afield, there have been extra-judicial killings, never-ending displacement, torture and interference.

Theirs has always been the ultimate test of America's purported promise of freedom and democracy. Pity the producers of Turning Point are too invested in this myth to fully understand.

Turning Point: 9/11 and the War on Terror is on Netflix

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.