How to set up a cafe business in a combat-torn city

The kebab restaurant owner stops what he is doing, looks up and shouts: “You are crazy!” He then returns to his packing, murmuring in disbelief.

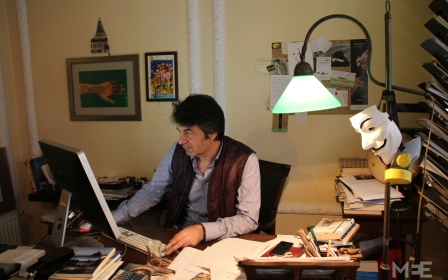

The target of his shock is Sehadet Citil, a thirtysomething Turkish journalist, who has proposed opening a shop in Diyarbakir’s ancient Sur

The shopkeeper's reaction is understandable: it’s early summer 2016 and Diyarbakir has been the scene of conflict between Turkish government forces and militants linked to a Marxist group which Western

The year-long operation is coming to an end but has left hundreds dead and more than 3,000 buildings in ruins.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

“Are you mad?” the shopkeeper asks again.

'This idea just popped up in my head'

Citil recalls well that day back in 2016. After she left the shop, she walked through Gazi, Diyarbakir’s main street and centre of everything that matters to the city of one million people.

The Grand Mosque of Diyarbakir. Ancient walls. Hans (enclosed courts) full of cafes and souvenir shops. Jewellery stores. Kebab restaurants. Gazi should have been full of tourists - but there was hardly anyone on the street.

Citil, like every Kurd, was familiar with the conflict. She had watched women of her generation trying to continue a semblance of normality, taking care of their children, looking after their homes and preparing meals, while fire fights erupted hundreds of metres away.

“This idea just popped up in my head,” she says. “I wanted to leave media, or whatever was left of it. I wanted to do something in my hometown.”

Citil's plan was simple – what if she could get some of the women to produce food for her?

There was a problem though: shoppers and tourists were steering clear of Sur. Citil then hit on a smart idea: follow the lead of small stores across Turkey and use Instagram to market and sell her produce.

“I would sell everything on Instagram to people who live in big cities. They wouldn’t come, but we could send things to them.”

And Citil already had a name for her brand: Hevsel Bahcesi which translates as "Hevsel Garden". It is based on Hevsel Gardens, the UNESCO World Heritage site, whose history goes back 8,000 years and which stretches for some 700 hectares from Diyarbakir’s city walls to the river Tigris. The area is still farmed in 2019, using the same traditional methods as generations before.

Sausages and spices

Citil started her business small from home, selling her mum’s dried peppers and pastes as a test run. Then she convinced seven more women in Sur to produce food for her, much of which was prepared in the roof of traditional Kurdish houses.

“You dry eggplants, peppers and tomatoes. You make pastes. They are tasty and people in big cities love genuine traditional food,” she explains.

From there, Citil started to purchase sausage, spices and similar produce from neighbourhood stores to resell online. The orders increased: by the end of 2016 she decided to expand.

In Sur she eventually found a traditional building, complete with the hallmark black stones, rented it after a comprehensive renovation and opened up as a cafe.

“I thought I should buy from Hevsel Gardens. I contacted some of the farmers. They started to plant organic basil, mint and peppers for me.

“I didn’t stop there of course. I began to get strawberries from Batman and quinces from Diyarbakir’s Dicle to make jams. All of them came from small producers, involving women and families.”

Most of Citil’s customers know her through Instagram: being a former journalist has helped her make contacts and publicise the business. Her feed, followed by nearly 40,000 people, includes video of her mother cooking jams and small pastries, destined for the cafe, and receives get hundreds of likes every day.

Now thousands of purchases are made from Hevsel Bahcesi every month, the bulk of which come from western Turkey.

'We need trust'

Citil’s vision for the business meant that she needed to find more women and more farms for supplies. It’s a plan that has taken her beyond Diyarbakir to the villages near by.

“My mum, Havva, is the real boss,” she says. “I just drive her door to door. We meet and have tea with dozens of producers. We want organic products. We need trust.”

The business now works with more than 70 female producers, who in turn use the money to help their own families: some buy fridges, others use it for education or livestock.

“In a village located in Dicle district, a woman started to work for us. And then she talked to other women living around. A half dozen of them. They now all work for us, selling us mint and basil.”

There are four people, including her mother, helping Citil to run the shop. But after three years she is still restless, still thinking of ways to grow the business.

A short walk through the narrow streets of Sur reveals that other traders and entrepreneurs have followed her example and opened up shops in the neighbourhood. Some offer breakfast, others sell souvenirs. The traditional stores – the old restaurants and the jewellers, the dessert sellers and the hans – have also returned. Sur is bustling again.

“They were all calling me mad,” Citil recalls of life three years ago. “They didn’t think things would go back to usual.

"Who is crazy now?”

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.