War, peace and ice cream: The parlour that stood the test of time

BEIRUT - Nestled into a 10-metre-square hole in a wall of a crumbling building in Beirut’s swanky Achrafieh neighbourhood, 62-year-old Mitri Hanna Moussa and his mother Samira are cutting fresh strawberries, grinding pistachios and preparing milk so that they can make some of Beirut’s most sought-after ice cream.

At any given time, the small shop delivers scoop upon scoop to an array of the neighbourhood’s patrons living in east Beirut. For Moussa and his mother, a queue meandering around the block is a daily sight.

Moussa’s late father opened the store in 1949, he tells Middle East Eye.“I was about eight years old when I started helping him. After school, I would come to the store and I’ve been obsessed with it ever since.”

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

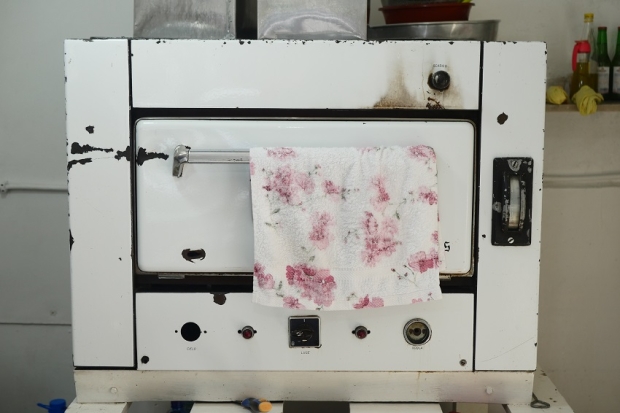

Although the store is modest in size and equipment, his father’s recipes have kept people coming for decades. Moussa’s only oven is even marked by a bullet from Lebanon's civil war.

Unlike modern dessert stores, Helwayat Salam (Salam Sweets) does not boast a never-ending list of ice cream flavours nor an array of treats. Everything is seasonal.

In the summer, don’t expect to find any maa’ moul –traditional semolina-based pastries stuffed with either pistachios or dates, which are especially popular during Eid and Easter celebrations.

The same goes for maakaroun – a deep fried, finger-shaped semolina sweet usually made on Eid-al Barbara, a holiday similar to Halloween where Lebanese Christians pay homage to Saint Barbara. She lived in the fourth century and is believed to have disguised herself as different characters to escape her father's persecution.

My father never told anyone his secrets, not even my mother

- Mitri Hanna Moussa

“In the summers we make ice cream and stop around October. From then on, we make desserts depending on the holiday. On Easter, it’s maa’moul,” Moussa explains.

But of all the treats, Moussa and his father are known for their version of 11 ice cream flavours. His customer's favourites are his take on rosewater, lemon and croquante (French for crunchy) – a house special marrying almonds and crushed biscuits in a milk-based ice cream.

“You can eat my ice cream at any time of the day. It’s not heavy like the ones you see in the stores now. When it melts, it’s not too sugary, it’s just like juice.”

Moussa's father kept the recipes secret from everyone in the family for decades, only passing them down to Moussa when he fell ill.

"My father never told anyone his secrets, not even my mother. So when he was sick, he passed them to me."

On a Tuesday morning at 10am, 32-year-old Karim Itani arrives at Helwayat Salam to grab a cone of his favourite flavours - lemon, strawberry and rosewater. Itani, a Beiruti himself, is not from the predominantly Christian neighbourhood of Achrafieh, nor does he work close to the shop.

“I’m from Ramlet al-Baida,” he tells MEE, a neighbourhood about a 15-minute drive away in West Beirut on a day without traffic. Laughing, he says it’s worth the drive to come to the other side of Beirut just for Moussa’s ice cream.

Moussa, an Orthodox Christian, interrupts and makes it clear that he rejects any semblance of divisions. “It’s not the other side. We are Lebanese. In Beirut it’s all one side.”

Lebanon’s bloody civil war, which lasted from 1975-1990, divided Beirut into the Christian east and the Muslim west, but the ice-cream connoisseur insists on throwing away all civil war notions of west versus east.

Sectarianism has no place in Helwayat Salam where bouza (ice-cream in Arabic) and sweets are made for everyone to enjoy.

‘Only winners eat here’

Moussa’s shop has a variety of names: Mitri’s, Hanna Bouzet, and Helwayat Salam - the least popular, but official name. Outside the store, you won’t find a conspicuous sign pointing you to the family’s shop - only an aging placard marked Helwayat Salam in old Arabic script just underneath an old Pepsi cola logo.

“Everyone forgets the name of the shop. They always just refer to us by our names,” he says laughing.

“My father’s name was Hanna Mitri Moussa, and you know in [Lebanon], people take their father’s middle name, so I’m Mitri Hanna Moussa. But there is a story behind the name [of the shop].”

During the 40s, Beirut’s well-to-do Achrafieh neighbourhood was home to al-Salam, a locally prominent football team of blue-collar workers.

My father used to say, ‘only winners eat at al-Salam'

- Mitri Hanna Moussa

“All the players were taxi drivers, construction workers, you know...people who worked in the neighbourhood,” Moussa recalls.

Moussa shares memories about the days his late father would go to watch matches at the pitch just 800 metres due south of Helwayat Salam. Often, Moussa says, his father would close shop to catch the evening’s game.

“My father used to say, ‘only winners eat at al-Salam’,” the son laughs, with a portrait of his father sitting on a shelf hanging behind him.

Today, the football pitch is long gone. Instead, a commercial shopping mall stands in its place. The namesake for his father’s favourite football team no longer exists. As a result, Moussa’s younger visitors no longer make the connection to the shop, instead correlating the bouza to the man himself.

War-time sweets, peace-time sweets

Moussa's family business has also withstood the test of time, surviving well beyond the end of the civil war in 1990 and the 2006 Lebanon war, which Israel waged against Hezbollah. The pockmarks left by bullets on the building outside are some of the only scars it has left on Helwayat Salam.

“I only remember him closing two or three times over the years. That was war. We all had to work and carry on our daily lives. He would only close when he was sick, because no one else knew the recipes,” Moussa says.

Having taken to ice cream growing up, Moussa never had big plans to go to university or leave the country despite the ongoing war. Instead, he wanted to learn the secrets of his father’s trade and someday take over.

“I always thought it was so much fun, but my father didn’t allow it. He advised me to pursue my education, finish college and look at other opportunities outside of this.”

Disappointed, he nonetheless followed his father’s advice and continued his education studying business. Never straying too far from the shop, Moussa was comfortably employed in a nearby bank.

In 2012, the shop closed more frequently due to his father’s ailing health. Sitting at home, he received a call from his father, asking his son in all seriousness if he would be interested in inheriting the trade.

That was war. We all had to work and carry on our daily lives

- Mitri Hanna Moussa

“I went to work straight away and handed in my letter of resignation immediately,” Moussa recalls proudly.

In the coming months, after his father passed away, Moussa had fully inherited the baton and was working on sweets day and night.

“I think my father saw that I had done well for myself. I had been working in the bank for a while. I had my own house and I was married with children who were comfortable. I think he probably felt it was ok for me to take over.”

Moussa has succeeded in sustaining the reputation that his father began decades ago, bringing veteran clients back on a daily basis as well as enticing neighbourhood newbies.

A changing neighbourhood

While he has been manning the shop with his mother for about six years, much has changed.

Next to the frail pre-war building, where Moussa's shop is tucked in, stands a towering contemporary residential building. Side-by-side, it’s a juxtaposition of Beirut’s rich and complex past and modern desire to exchange memories for a clean slate.

“This is how it is,” Moussa shrugged. “The buildings here are changing, people are changing. We were like family before, not neighbours. Everyone knew everything about one another, but it’s not only Achrafieh that’s changing, it’s the whole world.”

In the past decade, many war-torn and historic buildings in Moussa’s home neighbourhood were replaced by towering apartment blocks that the original residents could not afford, according to Moussa. This has become the norm throughout all neighbourhoods in both west and east Beirut as the capital has slowly reconstructed itself post-war.

When asked just how many kilos of ice-cream he makes on a daily basis, Moussa just laughs.

“I don’t know, I just work. Even if I did know, I wouldn’t tell you.”

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.