The silencing of the Douma Four: Still missing, one year on

“For three days, the voice of the muezzins echoed, but not with the call to prayer. These soft, sputtering sounds were lost in the wind before we could hear their full names. Every time we heard the megaphone crackle, we knew it would announce the addition of a new martyr to the many who had defied the ruthless road.”

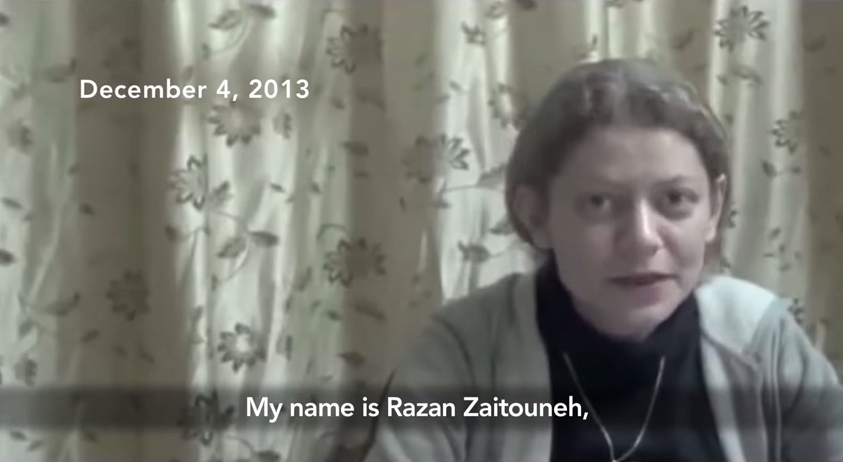

These were some of the last public words of Razan Zaitouneh, a prominent Syrian human rights lawyer and civil society activist, before her abduction from the besieged city of Douma, East Ghouta on 9 December 2013. Along with her colleagues - Wa’el Hamada, Samira Khalil and Nazem Hamadi (now collectively known as the “Douma Four”) - Razan was taken from her office at around 10.40 pm by masked assailants. Since then, there has been nothing but silence, with calls to find them going unanswered.

“We don’t know if she is alive. We don’t know if she is sick. We don’t know anything,” said her sister, Reem Zaitouneh via a crackly Skype connection from her flat in Lebanon. Seemingly disappeared off the face of the earth, the Douma Four have joined the vast ranks of Syria’s missing - the “enforced disappeared.”

On 9 December 2014, exactly one year on from their abduction, 54 organisations, including Human Rights Watch and Lawyers for Lawyers, have signed a press release urging their abductors to release them immediately.

Razan Zaitouneh: A face of the revolution

“I first met Razan when I was at university in 2007,” Bassam al-Ahmad, her friend and colleague, told MEE. “Friends and I were holding secret discussion groups talking about human rights, freedom of expression, and Kurdish rights. Razan joined us, talking to us about her work in human rights. It was dangerous for her, but this woman wasn’t frightened of working with men and spoke so clearly and passionately.”

It didn’t take long for Razan to become active in the revolution, co-founding the Local Co-ordination Committees (a relief and media network which quickly stretched across the country) as well as the Syrian Violations Documentation Centre (VDC). As one of the only people who wrote under her real name, the government soon took notice and summoned her for questioning. Yet she refused to leave the Damascus area, moving from house to house, avoiding checkpoints and minimising the use of her mobile so she could continue her work documenting abuses and assisting local NGOs. “Despite efforts to silence her, Razan spoke valiantly and courageously, bringing attention to those unable to have the world’s ear,” said Mariana Katzarova, the founder of Reaching All Women in War - an organisation which awarded Razan its 2011 Anna Politkovskaya Award.

She eventually settled in the “liberated” city of Douma, along with her husband Wa’el - an opposition figure who had already been detained three times during the uprising and who determinedly stood by Razan’s side - Samira - an experienced political activist who had been an active member of the communist party opposing Bashar’s father Hafez - and Nazem - a human rights lawyer and poet who was soon to publish his second volume of work.

Living under an airtight siege imposed by the government, Razan continued to receive threats - finding anonymous letters on her doorstep ordering her to leave.

Whilst this may have been in response to her public criticism of the idea that “ends justify means” and her documentation of violations committed by opposition forces, her colleagues at VDC believe it is more likely a response to what she stood for: free expression and a vibrant civil society. “When activists moved to ‘liberated’ areas, they thought they would be safe,” explains al-Ahmad. “But increasingly, here too they faced difficulties. Razan was supporting civil society and women’s rights - for some rebel groups and battalions, this clashed with their ideologies.”

No one knows who was behind the kidnapping of the Douma Four, though many have blamed the opposition group in control of the city - Jaysh al-Islam, part of the larger Islamic Front. “Douma is controlled by [Jaysh al Islam’s] Zahran Alloush, and the area is totally besieged by government forces,” said al-Ahmad. “Nobody could just come and take them without the armed group knowing. They control the area, and they should protect its people - so they must take responsibility”.

Friends and family have repeatedly called for news, contacting rebel leaders as well as governments who support them, but their efforts have so far proved fruitless. Jaysh al-Islam continues to deny any involvement in - or knowledge of - the kidnap.

Enforced disappearances

The silent abduction of Razan and her colleagues is part of a much wider trend of “enforced disappearances” in Syria - the arrest, detention or abduction of individuals followed by the total concealment of their fate and whereabouts. Thousands of powerful voices have been silenced by this tactic. The VDC believes that at least 1,200 are being held by members of the opposition - including of course, the self-proclaimed Islamic State.

The government, meanwhile, has long used forced disappearance as a method of control, but has taken it to a new extreme as a weapon for silencing opposition and spreading fear in the current conflict. According to the Syrian Network for Human Rights, 85,000 people have been forcefully disappeared by the state.

Few are untouched by these disappearances. Rami Nakhla, a Syrian pro-democracy activist who escaped the country on the back of a motorbike in 2011, told MEE. “It is hard to find a Syrian who has not been affected by this. Many of my friends have been detained, tortured, killed, or are still missing. Not one has escaped being hurt.”

In fact, abductions are so common that a new language has emerged. “The ‘aunt’s house’ is the term we use for ‘security centre,’” laughed al-Ahmad, “and some of the most infamous generals have been given their own code names too.” One notorious colonel in the air force intelligence branch in Harasta, Damascus, gained the name ‘Abu al-Mawt’ (literally, father of death), while another from the 215 military security branch in Damascus has been renamed “Sharshabeel” (the Arabic name for “Gargamel,” the evil wizard in “The Smurfs”).

But this dark humour cannot obscure the horrors faced by detainees in Syria’s many detention centres - which groups such as Human Rights Watch and Amnesty have highlighted. According to Claudia Scheufler, Amnesty International’s Syria campaigner, former detainees of both government and opposition groups have reported unimaginable living conditions and the use of varied and horrific torture techniques. Scheufler told MEE that cells are regularly overcrowded, prisoners have insufficient food, a lack of clean water and little access to sanitary facilities - many of them subsequently suffering painful skin diseases. Prisoners have reported being raped, beaten, electrocuted, burnt with acid, hung from the ceiling by their wrists and forced into stress positions - as well as other, more “inventive” techniques.

With such dire conditions, many of the “disappeared” do not survive imprisonment. The few who are released, meanwhile, often face ongoing physical and mental trauma. Not only are many in urgent need of treatment for physical wounds, malnourishment and disease, but most also have to deal with acute psychological difficulties.

“Their conditions are worsened by the fact that there is little medical assistance available in rebel-held areas,” explained Razan’s sister Reem, who has been part of the VDC’s informal “online hospital” - a “skype clinic” - which sets up links between trained doctors forced to leave Syria, and those who need help and advice in Syria. “People who have suffered in detention centres really need trained psychologists who will listen to them and look after them - but there are few of these in Syria now.”

Silencing Syria’s peaceful voices

Quite apart from the personal tragedies of those forcibly disappeared, the increase in abductions in both rebel and government held areas has impacted significantly on the ongoing struggle for civil rights.

With passionate voices silenced, and with fear and uncertainty surrounding the fate of those disappeared, it is becoming harder for others to speak out - and many have fled the country where possible. “In Douma, after they attacked Razan, a lot of activists we spoke to expressed how afraid they were,” said al-Ahmad. “We had to simply tell them to leave the area as it was too dangerous.”

Quite apart from the crucial work Razan and her colleagues did in documenting abuse when few international observers are admitted in the country, they also represented the peaceful voice of the revolution, which many worry is now forgotten in the chaos of an increasingly violent and complex war.

“Samira’s abduction a year ago along with Razan, Wael and Nazem was a blow to the Syrian revolution,” said Yassin al-Haj Saleh, husband of Samira and a Syrian writer and activist, in an email to MEE. “It has given us only gloomy prospects for the future.”

On the anniversary of their abduction, calls are being renewed for Razan and the Douma Four’s release - from closest friends and family to those who watch the Syrian civil rights movement from afar. “Razan was a dear personal friend of mine,” said Rami Nakhla. “Two years before the uprising started, my sister went to university one morning - and simply vanished. Razan stood with me and my family, calling me every day as we hunted for her in the secret police centres. Razan’s case will never be forgotten. We - the hundreds, if not thousands, of people who have been helped by her - owe her this.”

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].