Turkey’s Ottoman Hearths: Menacing or benign?

ISTANBUL – For a relatively new organisation, it hasn’t taken long for the Ottoman Hearths to instil a sense of fear and revulsion. They have increasingly come into the spotlight for their alleged involvement in notorious acts that include attacks on the offices of political parties, independent media outlets and journalists.

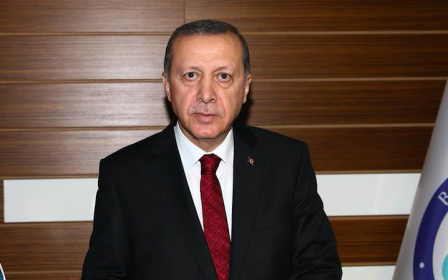

Established in 2009, the Ottoman Hearths now boast close to two million members across the country. Their stated goal is the promotion of an Ottoman system of governance and way of life. Both their leadership and members profess a profound devotion to Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan and the political party he hails from: the Justice and Development Party (AKP).

This devotion has meant that many see the Ottoman Hearths as an informal force used by the AKP to target its opponents. The AKP, however, has long been at pains to disassociate itself from the Ottoman Hearths and denies any links with the group, particularly any financial links.

The Ottoman Hearths, who preach a potent mix of religion and nationalism, first came into the spotlight when their members were spotted at AKP rallies wearing white burial shrouds. The message was loud and clear. They were willing to forfeit their lives on the command of their revered leader Erdogan.

Yilmaz Babaoglu, the deputy chairman of the Ottoman Hearths, is of the opinion that their actions have been misunderstood and that the wearing of the burial shrouds was simply a symbolic gesture.

“It was meant to show our devotion to our leader Erdogan. It doesn’t mean we want to die or kill anyone,” Babaoglu told Middle East Eye. “It was our way of showing our leader how much we appreciated his efforts to make us a great country again under the aegis of a ‘New’ Turkey.”

‘New name, old ideas’

Nuray Mert, a political scientist, is of the belief that in sociological terms this group essentially represents a new name for an old existing ideology. Mert also says it is difficult to ascertain if the Ottoman Hearths represent a violent threat until more is known of their structure and composition.

“This is just a continuation of the Turkish-Islamic synthesis that the right wing in Turkey has advocated ever since the 1970s and 80s,” Mert told MEE. “It is a neo-Ottoman right-wing irredentist approach to history and life.”

Babaoglu rejects all allegations that their members have been involved in various mob attacks in recent months, particularly after the inconclusive general elections in June.

“We don’t need to reply to these totally untruthful accusations. A court is the venue to respond to such claims,” said Babaoglu. “We neither condone a mob culture nor have we ever resorted to such means.”

Following the June elections, a spate of mob attacks occurred where primarily the offices of the pro-Kurdish Peoples’ Democratic Party (HDP) were targeted. Fingers were pointed at movements associated with the Nationalist Movement Party (MHP), which has been fiercely opposed to any peace process to resolve Turkey’s Kurdish conflict. These movements come with a previous history of resorting to street violence as a means to an end.

At the time, however, even the MHP distanced itself from such mob violence and pointed the finger at the Ottoman Hearths, which it said was an AKP-linked organisation.

During the same period between June and the November snap elections, independent media offices and journalists also came under attack. The lethargic police response to all these attacks also meant analysts perceived a link between the ruling party and the attackers, who were believed to be members of the Ottoman Hearths.

“We are an apolitical organisation. Our only aim is to promote Ottoman culture and yearn for a return to the glorious days of Ottoman rule. We have nothing against other political parties,” said Babaoglu. “If these other parties worked to serve our nation, we would back them just as much as we back the AKP. The MHP only makes these accusations because we have attracted a lot of members from the ranks of their organisations resulting in their election losses.”

In another instance, the Ottoman Hearths came under intense criticism when the then head of their Istanbul youth wing sent a tweet wishing that the suicide bomber whose action resulted in more than 30 deaths in the border town of Suruc on 20 July rest in peace.

“He was stripped of his membership immediately. He was not part of the organisation’s leadership, just a member,” Babaoglu told MEE. “We do not believe in ethnic or sectarian discrimination. We want to live harmoniously just like we all did during Ottoman times.”

The group has developed such an intimidating reputation that even plenty of hardcore AKP supporters fear and despise the group.

According to Mert, there is little ideological difference between the paramilitary ultra-rightist Grey Wolves organisation of the past and the Ottoman Hearths of today.

“While we don’t know about the paramilitary aspect of these Ottoman Hearths, they are similar in every other sense to the Grey Wolves. The only thing we can be sure of is that this ‘New’ Turkey is not at all different from the ‘Old’ Turkey,” she said.

Morality police in the making?

Another matter of concern is whether the Ottoman Hearths could signal the beginning of the process toward the creation of an unofficial force looking to enforce adherence to the ruling elite’s interpretation of morality and its world view.

“We have absolutely no intention of interfering in anyone’s lifestyle. We believe in coexistence,” said Babaoglu, but was quick to add: “This doesn’t mean for example that we will promote the consumption of alcoholic beverages. To us those are just as bad as narcotics.”

Mert believes the outright rejection of other lifestyles and values by such groups is because they were unintentionally excluded from the process of change in the first decades of the 20th century, both toward the end of the reign of the Ottoman Empire and the early days of the republic.

“These processes of modernisation, secularisation and such occurred in urban areas, therefore excluding a major proportion of the populace, which was rural – the same as in other Muslim countries,” said Mert. “The loathing of anything different to their accepted norms today by these right-wing conservative groups is basically a response to that exclusion.”

“We are not interested in the length of women’s skirts and such things. Just look at our women’s wing. We have all types of members. Heads covered, uncovered and everything in between,” said Babaoglu.

The rate at which the Ottoman Hearths are growing and creating an impact became clear when the office of the presidency sent a note to the prime minister's office on 12 November, stating its discomfort with the group’s portrayal of itself as having close ties with the president. As a result, the prime minister's office sent out a circular to all government departments on 4 December alerting them of potential approaches by the group’s members.

Babaoglu insists the Ottoman Hearths do not have any formal links with Erdogan and the AKP, and that they are independently financed.

“We don’t even accept donations or membership dues. Our funding is fully private. We channel funds from our private businesses for charitable activities,” he said.

“Yes, we love our nation’s leader Erdogan and his AKP. We also believe the AKP’s enemies are the nation’s enemies. But none of this means that we are part of the AKP or that we physically attack the party’s enemies.”

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].