Reviving the forgotten flavours of the Ottoman palace kitchen

Fusion is a dirty word in kitchens these days. All the rage in the 90s (see California rolls and Chinese chicken salads), fusion cuisine is now seen as passé, fit only for the yuppie Wall Street types satirised by Bret Easton Ellis in American Psycho.

People eating fussy food in fancy restaurants are easy to make fun of. But not only is fusion food a natural outgrowth of an increasingly interconnected world, it’s not even anything new.

The Ottoman Empire, as one of the largest, longest-lived, and most diverse empires in modern history, was the incubator of a truly cosmopolitan cuisine – perhaps the world’s first fusion food. The cuisine developed by folding in techniques and ingredients brought down through networks of trade routes (part of what’s known as the Silk Road) from the far reaches of the empire – the Caucasus to Tunisia, from the Balkans to the Persian Gulf.

While this tradition of imperial Ottoman cuisine eventually fell dormant after the foundation of the modern state of Turkey, food historians (followed closely by restaurateurs and investors) are engineering its comeback.

Spearheaded by Asitane restaurant and its team of researchers and chefs, a rash of new restaurants has launched, featuring modern recreations of food served to the sultan and his harem, dignitaries and guests.

For Asitane’s cooks, though, it wasn’t as easy as opening up a dusty old book and following the instructions, owner Batur Durmay tells MEE in the restaurant’s ivy-trellised patio in Istanbul’s Edirnekapı neighbourhood, a stone’s throw from the fifth century Chora Church. What kitchen records were available proved to be of limited use.

“Medieval cookbooks weren’t written to instruct,” says Anny Gaul, a doctoral student in Arabic literature at Georgetown University, with a special focus on food history and medieval Middle Eastern cuisine. Instead, “they were written to record what happened in the kitchen, just like court annals recorded what happened in the court”.

After conceiving of the idea at a family meeting in the 1990s, Durmay (an industrial plastic moulds manufacturer by profession) and his research team began combing Ottoman kitchen ledgers and the treasury’s accounting books, cross-referencing them with the diaries of dignitaries who had visited the court around the same time.

“Because of the lavishly detailed recordings of palace events, if you know the date of an event you can go back to the treasury and kitchens and see what was purchased,” Durmay says.

With descriptions of the finished dishes, and a list of what was purchased, all that was left to do was figure out how to get from A to B – a feat which itself took a few years of testing and training staff to accomplish.

The sweet life

One of the most notable differences between this food and what we’re used to eating is that it’s much sweeter, flavoured liberally with fruit and sweet spices.

A plate of standard-looking hummus comes out, but it tastes of cinnamon, nutmeg and currants, sweet flavours I associate with Christmas, instead of the sharp garlic, salt and rich tahini we’re used to.

Middle Eastern cooks only started making hummus with savoury ingredients including tahini, a sesame seed puree, in the 19th century, Durmay says. Asitane’s hummus is made from a recipe dating from 1469.

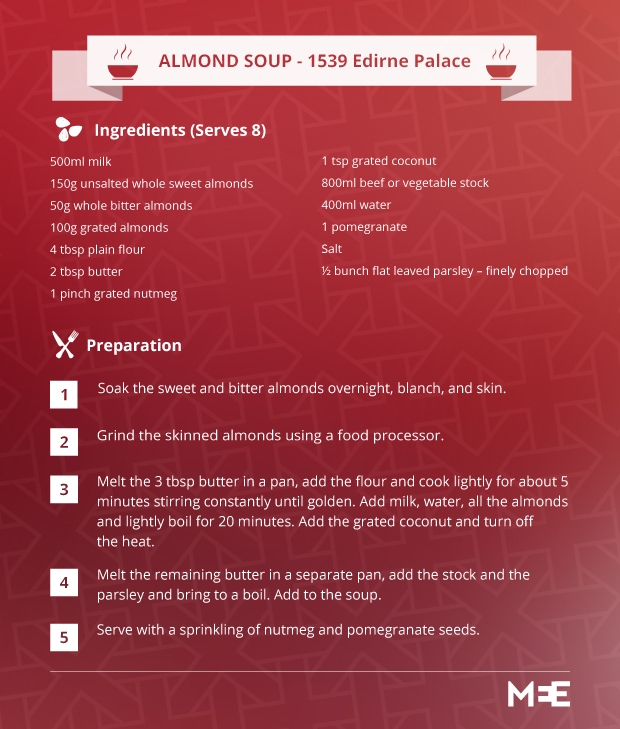

The pattern is repeated in other dishes as well. Chilled almond soup, when served in the western Mediterranean traditions of Spain and Morocco, features spicy pepper paste, garlic and olive oil alongside the creamy pureed almonds. Here, the soup is a confection, spiced with cinnamon and nutmeg, with pomegranate seeds as a garnish.

Asitane’s chicken stew features meltingly soft dried apricots and raisins in a thin broth perfumed with cinnamon and cloves, rather than root vegetables and aromatics like garlic and onion in a flour-thickened roux, as we would expect in the West.

The idea that a meal shouldn’t include a sweet dish before the dessert course “is an innovation of modern French cuisine from the 18th century,” says Gaul. “Modern French cuisine was exported as the standard of high cuisine in the 19th century, so we’ve become used to the idea” of savoury followed by sweet.

Ottoman-era court cuisine featured sweet dishes throughout the meal, she speculates, for two primary reasons. First, there was a “heavy Persian influence” on Ottoman palace food. The Persian Empire had a “well-developed court cuisine centuries before Islam” which prominently featured fruits including plums, apricots and pomegranates, as well as dried fruits like raisins and prunes.

The Persian influence on the food reflects a larger cultural turn eastward beginning in the 8th century CE. “When the Abbasid dynasty founded Baghdad in 762 CE and moved its capital there [from Damascus, the seat of the prior Umayyad caliphate], a lot of Arabic culture started drawing inspiration from Persia,” Gaul explains.

This is a trend that would gather strength in the centuries that followed, and spread to the Ottoman palace and the Muslim world beyond, all the way to Morocco and Spain.

A more practical explanation is that sugar was very expensive during the Ottoman period. “To make a sweet dish would have been showing off how refined your kitchen was,” Gaul continues. “It makes sense that any Mediterranean court cuisine would have featured a lot of sweet dishes.”

Lasting legacy

For Durmay, the cuisine of a country – or empire – is a potential indicator of its very essence. “Gastronomy is very strongly influenced by the economic, political and cultural state of the country,” says the businessman, for whom Asitane is a labour of love (all the restaurant’s proceeds go back into research and training, Durmay says).

“The Ottoman cuisine was established when the Turks conquered Istanbul [in 1453, under Mehmet the Conqueror]… this was the first time we started to live in a city with infrastructure, water works, roads, markets, etc. Before we took Istanbul and established it as the capital, all the sultans were constantly on the road.”

“A history of the Ottoman cuisine is to an extent the history of the settlement of the Turkish people.”

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].