Refugees from Middle East rub along with still homeless Serbs

KRNJACA, Serbia – Dusanka and her husband Milan have been shifting around from refugee camp to refugee camp for the past 20 years but the latest, Krnjaca, some 20 minutes’ drive from central Belgrade, has been their home the longest by far.

Out front, there is a well-kept but busy garden filled with flowers, lemons and vegetables. Inside the walls are lined with pictures of extended family and old towns and churches in Krajna, an eastern part of modern-day Croatia. It’s here that the elderly couple were born and married and eventually fled.

“Our people are cursed,” said Dusanka who left with her two sons to Serbia in 1991 as the region’s wars for independence grew ever bloodier. Before they ended 10 years later, 140,000 people would have lost their lives and four million their homes.

“We lost everything. It is all gone - our home, our community, our families have all scattered. Milan was detained in a war camp until 1995. Me and [my two sons] left but he was there. We didn’t know if we would ever see him again,” she adds, her eyes still welling up at the thought.

As the war dragged on, the largely Serbian Croat refugee population was bolstered by those from Bosnia and Macedonia and later from Kosovo. Today, the Krnjaca camp is a microcosm of this exodus and houses largely elderly residents from across the ex-Yugoslavia.

In the last few years, however, Dusanka and Milan have gotten a whole new set of neighbours at her government-funded camp from more recent conflicts in the Middle East, Africa and central Asia.

“We used to see a lot of people from Afghanistan and Somalia but now there are so many from Syria and Iraq. More people come every day,” said Dusanka.

“It can be difficult to communicate. I mainly say a few words in English and just wave my arms around. Milan’s is worse – he’s very deaf,” she laughs. “But we try. We know how hard it can be. In the winter women and children were coming in with no coats and no shoes.”

“We let them wash their clothes in our washing machine and offer food.”

Dusanka is careful to offer all guests customary shots of a potent local liquor called rakia, regardless of the time, and rolls out droves of hand-made pastries.

Much like the Arab world, customs here dictate waiting on your guests hand and foot and require visitors to politely consume the vast offering.

“We get on with them well – much better than our own people a lot of the time. Us [Serbs and ex-Yugoslavs] we always have some problems with each other. Some always think they are better than others and I am disappointed in that,” Dusanka said.

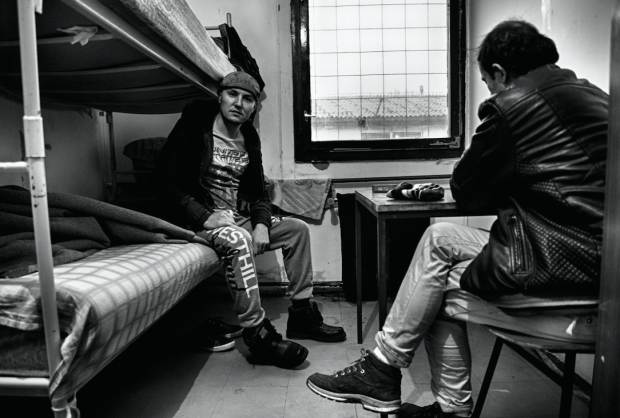

Despite this, many of the new arrivals say they don’t feel at home and complain of ill treatment at the hands of camp authorities.

Camp controversies

Fatima fled central Syria earlier this year with her young son and daughter shortly after her husband was killed by Islamic State.

“IS have started to grow stronger. They were slitting people’s throats and taking everything – from livestock to our homes. My family is all still there but after [my husband] was killed I just had to get out,” she said.

She says she walked all the way, her horribly swollen and bruised ankles collaborating her trials.

“I’ve seen a doctor here [at the camp] and they gave me medicine but they didn’t have what I needed,” she said. “I have also asked for new shoes and I know they have them but [camp management] won’t give me any. The light in my room doesn’t work, we can’t see at night. I asked them to fix it but they have not.”

Centre managers are not authorised to talk on the record, but they stress that they are doing the best they can with the resources they have and that the standard of care they provide is some of the best in the Balkans and Eastern Europe. They are proud to talk about art classes they offer and the level of cleanliness, which they insist is consistently high.

One staff member here quips that conditions here are better than for many Serbs who have seen their economy ravaged and are not able to have three meals a day, often rummaging through dustbins for scraps.

However, Tarek, who used to be a government civil servant and did not want his real name to be used, also complained about the conditions.

After travelling for only two weeks he arrived two days ago with his eight-year-old son and plans to spend a few days more days in Krnjaca before heading north.

“They would only give me limited supplies like soap but the biggest problem is that there are no mosquito nets. I told the management but they did nothing. It is difficult to sleep and we are here to rest,” said Tarek, who is originally from a village north of Raqqa but has lived in the Syrian government stronghold of Tartous for more than 10 years.

While Tartous used to be regarded as relatively safe, Tarek insists that opposition forces have been gaining ground and clashes edging closer.

“There has been shelling on the outskirts of town for a while. We don’t know what will happen so we decided to leave while we could,” he said.

Ahead of his departure, Tarek brushed up on his German and English. Both are basic but his family went one step further to try and secure a highly prized asylum application in Germany. While 202,815 asylum applications were made there in 2014, only 26,080 were approved.

“I am a Sunni and my wife an Alawite but we both converted to Christianity,” said Tarek.

“Few people know about this. In Islam converting is punishable by death but when we decided that we would leave for Europe, we wanted to show that we were committed to integrating. To living side-by-side with our neighbours.”

“I know that people in Europe are scared of many Muslims coming over. I understand this. There are so many terrible things going on, like Daesh. So I think if you want to come to Europe you should convert. If not, go to Saudi Arabia. They made the problems worse so why are they not taking in more people?”

Tarek says he long ago stopped caring about religion, nationalism or loyalty to any particular faction.

“All I wants to do is keep my only son safe,” he said, the anxiety in his big eyes giving away his fears that he might not be able to do so.

“We need to make it through Hungary. I don’t trust my son with smugglers so I will use my GPS to cross. But it is difficult, and I am scared. We will have to cross in the dead of night and hike through the forests.”

Border troubles

Refugees usually only stay in one of Serbia’s six asylum centres for no more than a week. In Lojane, which has a capacity of 250 to 300, 1,665 people came and went from January to the 1 May.

From there they head north to the Hungarian border. Some will get smugglers to take them directly but other will follow the old railways north or get taxis to drop them off at a no-man’s land near the border town of Subotica which acts as a major crossing point. At the height of the migration peak earlier this year hundreds of people crossed through these woods illegally each day.

Illegal migrant camps began springing up last year and now have dozens and sometimes hundreds of people simultaneously holing up in abandoned factories, or more commonly in tents or in bushes.

Conditions here are hard. In the winter some migrants froze to death and there is little food, water or shelter. Smugglers come and go as they please and some migrants said that they feared being robbed by other migrants.

Some of those who get here say they are shocked at what they find. There are no facilities of any kind to help them here, apart from a motley crew of volunteers led by a local priest.

Two Iranian Christians in their twenties who just arrived said that they are desperate to get any kind of government or NGO assistance.

“Where is the UN? Please? There must be some kind of UN facility here?” said one of the men, who said he was from northern Iran but did not want to give his name. “Last year I tried to get to Australia and there was a lot of assistance in Malaysia. Here I have not seen anything. We are desperate.”

“We are Christians and we are persecuted in our country,” he added in flawless English. “When [the people we were travelling with] found out, our smuggler from Albania just took everything. We don’t have our documents, our phones or any money at all. How are we even going to contact our families?”

At the behest of the EU, which felt that having centres so close to the border would encourage migrants to cross, the government has not opened any facilities this far north. The closest camps are all the way back in Belgrade some 120 kilometres away.

The two Iranians said they were thinking of maybe doubling back.

“We have come this far but I don’t know how we will go any further,” he said. “Getting to Germany or Sweden feels impossible right now.”

*This article was shortlisted for the UN's 2015 International Labour Organisation award for journalistic excellence on migration.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].