From Syria to Serbia: The migrants' Balkan backdoor

BELGRADE - A month ago Abu Khaled used to be a teacher, living what he described as a comfortable life in a Damascus suburb. Since then, he has travelled more than 1,500 kilometres by land and sea and so far spent 5,000 euros ($5,600) on smugglers. He has survived a journey in a “death balloon” in the dead of night, walked for days on end, and been crammed into the back of a van with a dozen other refugees and illegal migrants desperate to avoid police.

He now sleeps on a park bench in central Belgrade, shielded from the sun or rain by old pizza boxes. He says he won’t stay long but that he first needs to get his hands on a further 3,000 euros ($3,400) to pay another smuggler to take him the rest of the way to Germany.

Abu Khaled’s journey might be extraordinary but it is in no way unique. He is just one of tens of thousands of refugees and migrants who are expected to try and enter Europe through the so-called Western Balkan route this year as the exodus from parts of the Middle East and Africa continues.

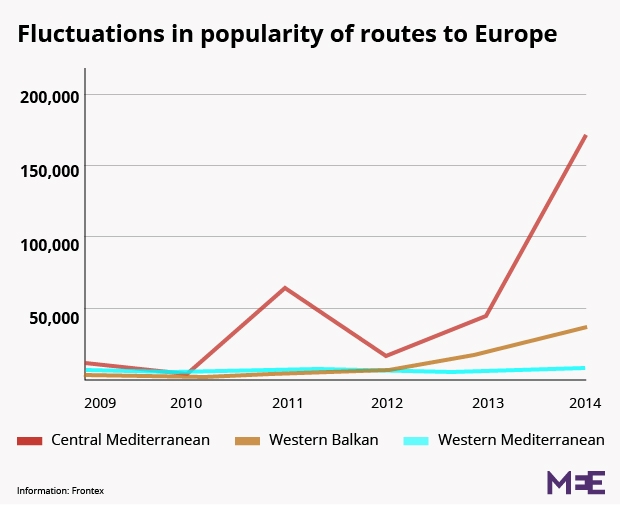

The route has garnered much less publicity than rival channels into the EU, such as the short but deadly sea crossing from Libya, but it too is growing in size, more than doubling from year to year.

In 2012, just 6,390 people crossed through this largely overland route to the EU, according to the EU frontier agency Frontex. In 2013, the number had risen to almost 20,000 and by last year some 43,360 were believed to have come this way.

In the first four months of the year, almost 40,000 had already crossed - a more than threefold increase based on the same period last year. Some came from Kosovo and Albania, but many others from Syria, Iraq and Afghanistan. With the warmer weather now upon us, further spikes could yet be around the corner.

The jump is largely being attributed to the further deterioration of security in places like Iraq and Syria, as well as shifts in EU border and asylum policy, but the catastrophic death toll in the Mediterranean, where at least 1,800 have already died this year according to the UN, is also playing a part.

Abu Khaled and his group of six male travelling companions aged between 16 and 60, who all say they left Syria in the last two months, told Middle East Eye that they chose this route out of a mixture of convenience and safety.

But while the overland route might be seen as less hazardous, many have been killed attempting it, either drowning in illegal boats or dying on the roads as smugglers ferry growing numbers of people in the same beat up cars and vans.

Those who survive risk being beaten up by smugglers or the local police, or even worse, being detained and put into the asylum system in countries like Hungary, effectively killing their chances of claiming asylum in their desired country forever. Ultimately, only the lucky few will make it to their preferred destinations such as Germany, Sweden or the UK.

The road less travelled

For the average Syrian or Iraqi, the long journey to Europe starts in their home country from where they venture to Turkey, either by foot, bus or car.

Turkey can then either be a short stop on the way to Europe, or a longer port of call. Some refugees and migrants spend years in Turkey, either travelling once they have exhausted all their resources and begun to see Europe as a last resort, or once they have acquired enough money to brave the journey. With smugglers asking anywhere between 1,500 euros ($1,750) to 4,000 euros ($4,500) just to get you as far as Albania or Greece, this can often be a long wait.

From Turkey there are two main ways that people try to access northern Europe.

The more direct way, known as the East Balkan route, takes you by land to Bulgaria - however notoriously harsh the treatment there. Additionally, the construction of a long border fence with Turkey has meant that many are choosing the longer way round.

The alternative is known as the Western Balkan route. It takes you by sea to either Greece or Albania, most likely in “death balloons”, the name widely given to small inflatable vessels that ferry people illegally across. From there, the two branches reunite in Macedonia and then go on to Serbia from where people hope to enter Hungary and make it to northern Europe.

Many walk for days on end, sleeping in forests or abandoned houses and factories when they can. Those with more money tend to throw their lot in with smugglers in overcrowded cars, cabs and trains, often lodging in cheap illegal accommodation. Whichever way you choose to go, however, the route tends to be treacherous. Many have drowned, and others have been killed or maimed on the roads.

Journey through Greece

“We took a small boat from Turkey to Greece,” said Abeer, a Sunni from Baghdad who is travelling with her husband and three young children in hopes of reaching Germany and seeking asylum.

“There were about 40 of us on it. We left at night and it was very cramped. The journey was difficult. The children were scared, they cried a lot. I was worried the boat would sink.”

The family was eventually dropped off on a deserted island where there was no food, water or shelter. They had to wait there for a whole day until another smuggler came to pick them up and take them to a separate island. Once there, they were abandoned and told to make their own way to the nearest village, a full day's walk away.

According to the family, there was only one policeman on the island. It would be a further day before they received any assistance from the Greek government.

Like all EU member states, Greece is supposed to fingerprint people once they are apprehended. Illegal migrants can then be detained or repatriated, while asylum seekers must be awarded special treatment until their applications are processed. In reality, the conditions for all those discovered in Greece don't differ much, with Amnesty International dubbing them a “living hell” and most migrants trying their best to avoid detection altogether.

Under the Dublin Regulations, which manage EU asylum procedures, asylum seekers can only lodge a request in the country where they are first registered and cannot subsequently apply in Germany or elsewhere.

However, there have been reports that the Greeks – along with other border EU countries like Italy and Bulgaria - are looking the other way in hope that the refugees will make their way north.

Those unwilling to risk detection in Greece usually therefore take “death balloons” to Albania where an altogether different and far less regulated danger awaits them.

A smugglers' paradise

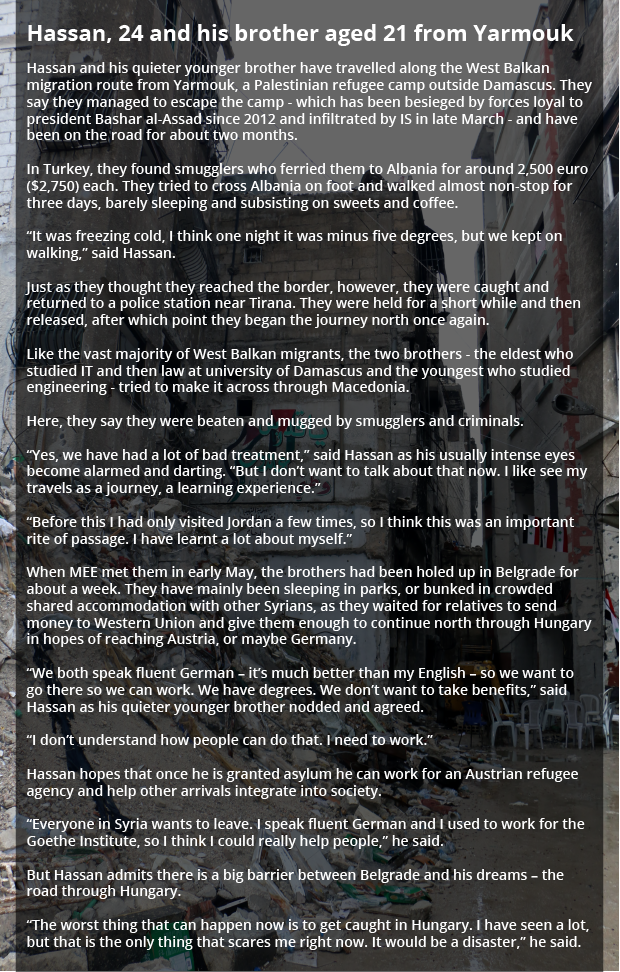

Two Palestinian–Syrian brothers, who escaped from Yarmouk camp near Damascus in April, claimed that they had been held by Albanian police twice and had repeated run-ins with smugglers and criminals on their journey north.

“We walked 120 kilometres to the border with Macedonia,” said Hassan, a 24-year-old IT graduate turn law student who used to work for the United Nations agency for Palestinian refugees (UNRWA) before aid was cut off from entering the besieged camp.

He proudly showed off his old UN worker ID, but while the photo was only taken a few years ago, Hassan is noticeably older. He has dark, red circles under his eyes, and grey hairs now spread out from his temples.

“It was early April, so it was still extremely cold, I think it fell to below zero at night. We walked almost constantly and didn’t sleep,” said Hassan, who did not want to give his real name.

“We eventually got to the border but the police caught us. That night they drove us all the way back. When they released us, we had to do the journey all over again. It was very hard, but we knew there could be no turning back. We have nothing to go back to.”

Hassan says that he feels that the countries along the West Balkan migration route are not abiding by the 1951 Refugee Convention. He listed off the charter's clauses and the protections he is entitled to effortlessly, the rules and regulations rolling off his legally versed tongue.

“I want to stress that we are not migrants, we are not here for economic reasons. We are refugees,” he said. “The police [and people here] don’t care about the difference.”

Hassan claims that he and his brother were also roughed up by criminals and had some of their money taken on the way, but the worst part of their trip was yet to come.

Macedonia’s mafia town

The Greek and Albanian branches of the Western Balkan migration route merge in Macedonia, a small former Yugoslav republic that escaped the worst of the bloody independence wars in the 1990s but has struggled since then.

It’s here that most refugees and migrants MEE spoke to described seeing the worst abuses and claimed that smugglers and criminals operated practically in the open.

Three separate Syrian men who travelled through Lojane, the last border stop before Serbia, said that they had been held at gunpoint. One claimed the criminals held a gun to his child’s head too and made the rest of his children watch while they took the last of his money. Another said that on several occasions, bandits made his wife and baby son watch as they frisked him and took his money, including a secret stash he had sown into his trousers.

“As you walked [through Lojane], you were stopped at every house you passed. All of them had automatic rifles and they all asked for a specific amount of money,” said the man who came from Aleppo two months ago but did not want to give his name.

“It is run by the mafia. Pure and simple. There is no police anywhere near there. I left Syria to get away from guns but I have seen a lot right here.”

Many who travel through need medical attention for bruises and wounds sustained in beatings. People have come in with broken bones, open wounds and head injuries. Some have lost eyes. Others have lost limbs.

A Syrian refugee told MEE that they were held in a warehouse that is being used as a holding cell by smugglers. Aid groups admit they have been hearing similar tales.

According to the reports, the smugglers hold people here until they pay their way out. If they cannot pay, or cannot pay enough, a family member is kept there until someone eventually coughs up. It’s not clear what happens if the family is unable to muster the sums necessary.

These smuggling and criminal networks extend into Serbia, one of the last ports of call for migrants and refugees journeying to the EU. With Macedonia on its southern border and Hungary to the north, Serbia is the heart of the Western Balkan route.

As the migrants and refugees pile up in record numbers, and the EU member states continue getting tough and demanding that more be done to stop the flow, Serbia – no stranger to bloodshed and the dire consequences of migration - threatens to be at the epicentre of the unfolding migration battle.

(Part II of this report focuses on the situation in Serbia)

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].