'Who can do that?' Kurds forced out as Turkish city bulldozed

SUR, Turkey - Walking through the narrow, winding streets of the Alipasa neighbourhood in Sur, the cobblestone pathways feel eerily empty.

Most residents are still scared to leave their houses after a devastating conflict between Turkish security forces and the outlawed Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK), waged primarily in the months of December 2015 to March 2016.

While today it appears peaceful, there remains a palpable sense of tension in the air. Heavy machinery and sounds of destruction can be heard in the background.

Rounding one corner, armoured police vehicles block the road.

An elderly Kurdish woman sits in front of her house, listening to the sound of bulldozers knocking down the walls of her neighbours' home, and waiting for the moment when police decide it's time for her to move on, and vacate her property forever.

Sur is the de facto old city of Diyarbakir, the largest city in Kurdish-majority southeast Turkey.

At least 60 percent of the entire Sur district has been expropriated by the government

- Amnesty report

Alipasa is one of the six districts of Sur, all deeply affected by the war and the destruction it wreaked.

The Turkish state fought with tanks and helicopter gunships, with the aim of taking control of the city from the PKK, who had dug trenches and built barricades throughout the streets.

Indefinite curfews were placed on the residents of Sur during the fighting, restricting access to food and water supplies.

According to an Amnesty International report released in December 2016, "all or nearly all of the roughly 24,000 residents of the six neighbourhoods of Sur under curfew left their homes".

Many were not able to return as their homes were no longer standing. For those who could return to Sur to rebuild their lives, they are now facing a second round of displacement.

Since the war, "at least 60 percent of the entire Sur district has been expropriated by the government," says Amnesty.

A distraught 30-year-old woman, named Esra, approaches, surrounded by children and other mothers.

She has just come from her friend's home where, as they were sitting talking, police and military arrived to announce they would immediately start knocking it down. Bulldozers have already got to work.

Memories lost

They were crying together, she says, lamenting the memories to be lost, along with her family's home. The small quantity of possessions she was quickly able to gather are being temporarily stored in Esra's home.

"Today it's going to be you, tomorrow it's going to be me," Esra replied with empathy.

For Esra knows that she faces the same fate.

Despite the war, only a portion of the districts were destroyed and rendered unliveable.

However, what destruction was caused seems to have provided the Turkish government with the perfect opportunity to enact the long-sought after "redevelopment" of the southeast.

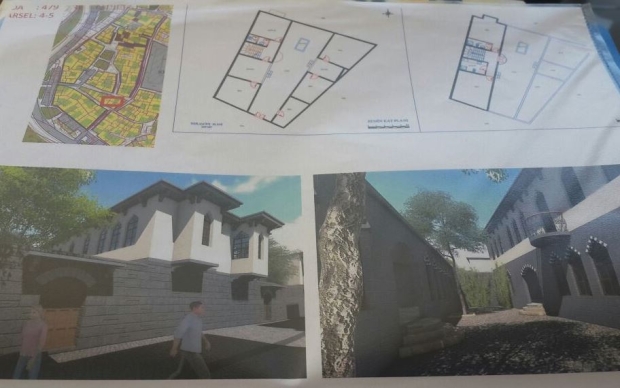

"They say it's a plan for ‘protection,' but I remember [President Recep Tayyip] Erdogan saying years ago that it was his dream to redevelop Sur, with the aim of rebuilding it in true Ottoman style," Mimar recalls.

Erdogan stated, in 2011, "with the projects we are planning to implement in Diyarbakir, employment will increase in the province and we will make Diyarbakir an international tourism destination," according to the Guardian.

And more recently, after the Turkish military operation had ended, then prime minister Ahmet Davutoglu echoed the president's desires, stating that Diyarbakir "would need urban renewal even if these events hadn't happened. We'll rebuild Sur so that it's like Toledo: everyone will want to come and appreciate its architectural texture."

These statements don't fall in line with the current demolition being sold as a security plan.

Security plan?

The designs show Sur will be rebuilt with 15-metre wide streets, enabling armoured vehicles to patrol, plus six new, fortified police stations.

"They don't need to destroy all the neighbourhoods just to make a few bigger roads," Mimar says, with scepticism in his voice.

Esra starts yelling, passionately trying to explain their situation. A story future tourists to the new district will likely be unaware of.

"The government takes all the lands we have. The lands that belong to our fathers and grandparents. Every time we got something, they took it away from us. All the time they are doing that. This is why we remain poor."

Esra was born in Mardin, though moved to Diyarbakir as a bride and now has three children.

Her family has lived in their home for seven years, borrowing money from the bank to buy it for 60,000 Turkish lira ($17,100) in 2010.

Esra has calculated the current value of her home to be over 125,000 lira ($35,500), taking into consideration inflation and the effect of the war on property prices.

But the government is saying they will give her 40,000 lira ($11,360) when they demolish it, she says.

Neither the local municipality nor the central government have responded to a request for comment about the development works in Sur.

With only her husband's basic income Esra says that with the minimal payment offered by the government, they will not be able to buy or even rent another home.

They are doing this because they want to make a profit

- Herdem Doğral Mimar, Diyarbakir Chamber of Architect's Board Member

Having to pay out more for rent or on a mortgage will mean even providing for their three children will become a struggle, she adds.

Mimar, the Chamber of Architects board member, is concerned the government are offering such a low payment for people's properties.

"They are doing this because they want to make a profit," Mimar says.

Mimar explained the new houses being built in place of the demolished homes will be sold for a far higher value.

Many families are refusing the money offered from the government on principle that the price is too low, leaving them with no home and no deposit to buy a new home.

No option to fight

Esra feels she has to accept; she has no option to fight.

"If Europe can't handle Erdogan how can I?" she says, attempting to illustrate just how small she feels, when faced with such Leviathan institutions and bureaucracy.

After the coup of July 2016, Ankara removed most of the municipality leaders in the southeast, generally run by the Kurdish HDP, and replaced them with state supporters.

"There are no places we can go to fight for our rights," Esra explains.

As Esra talks, rapidly switching between Kurdish and Turkish, police keep a watchful eye and occasionally walk over to the crowd of people gathered around, apparently attempting to ensure their presence is felt.

Esra's husband's family has lived in the central Sur district for 30 years. They are now trying to look for another house to move to, but given the little savings they have, they know it will have to be far from the city centre.

But wherever they move next, they know they won't know anyone there.

All of their friends currently live nearby, in the Sur area. "It's a neighbourhood," Esra says, describing the community as having the feel of one big family.

Even the market owner helps them in everyday life, allowing them to buy food on an informal credit system when funds are tight.

"Sometimes we don't have money, so we pay him the money later.

"In other areas there are only big supermarkets, we wouldn't be able to do that in these places."

Displaced far from home

The latest wave of evictions began at the end of April 2017, though the bulldozers first arrived after the war ended in March 2016. Esra says the demolition works are also bringing chaos and danger to the area.

Rats, snakes and scorpions have made homes in those buildings still standing.

"We are wondering if we will wake up tomorrow morning with our children dead or alive," Esra says, referring to the snakes and scorpions' deadly bite.

Her family doesn't know when they will be evicted - it could happen any day now.

Esra and the other mothers mention we should move off the streets because it is too dangerous to talk so openly with military and police personnel on the watch.

They talk of going home to clean the house but then laugh, knowing it is now a pointless exercise.

"They can kill us because we don't have a life anymore, that's why we're not afraid," Esra says, gesturing to the police.

Amnesty International's Turkey researcher, Andrew Gardener, explains how these home evictions are just the latest in a long string of trauma and disruption for the local residents, already having been forced to leave their homes during the period of fighting.

"They came back after being ransacked, got their homes together and are now being sent out a second time. It's an ongoing trauma from then till now," Gardener tells MEE.

Gardener mentions how unlikely it is that these people will own their own homes again in the future.

"If you look at the market value … of the new development, the land and the new houses are going to be very valuable," he explains.

The current residents will not afford to buy in the area again.

More than just a neighbourhood

It is clear Sur is a special place. With no cars, children used to play freely in the narrow streets and neighbours would converse openly outside. Since the war, many people, children especially, are too traumatised to leave their homes.

"It's not just a place to live, it was a support network as well. Large extended families lived in adjacent houses on the same street. All these things have been destroyed," Gardener adds.

It is these networks the state is trying to stop with the development plan, he says.

And Gardener is not convinced by the government's recent argument that the houses were so badly damaged during the conflict that they have to be knocked down.

However he believes the state was not primarily motivated by profit, but by a desire to permanently displace those seen as potentially problematic.

"It's clear there was a plan in place to respond to this genuinely problematic security situation of people armed in these neighbourhoods and (the PKK) erecting barricades and trenches. It was to engage militarily with these groups, displace the people, knock the place down and rebuild it in a way so they can hold it so it will never happen again."

Back on the streets of Alipasa, a Kurdish woman holding a young baby grabs her 18-year-old daughter to speak of the situation their family is facing.

The mother runs inside her home, around the corner from the house being demolished, as police patrol the area. The daughter, Hayat, leads the way upstairs to a brightly lit and colourful loungeroom, decorated with family photos. She says we can be relaxed here.

There are 11 people in her family. Two younger brothers and a sister are still in school, though during the fighting last year they couldn't attend for one and a half months. When they finally returned they were scared, and still remain stressed.

I don't want to leave where I was born and spent my whole life

- Hayat, Sur resident

"There is no joy anymore," Hayat explains.

Hayat was born in Diyarbakir and has always lived here.

"We are really tired of this life, we want to live in a nice neighbourhood, and have a nice life. I'm sick of it," she says with anger in her voice.

As she talks there are people screaming down the street, fighting with the police in two armoured cars who have come to demolish their house. Hayat explains the family haven't been offered any compensation for their home.

Her family doesn't know when they will have to leave their own home but they know it will be soon.

"I don't want to leave where I was born and spent my whole life," Hayat continues.

"When they come to take the house my whole world is just going to end," she says, becom emotional.

"I want to resist. They will demolish my home over my dead body or I'm going to stay here. No one can move us from our home. If they have a conscience they have to ask themselves how they can do that to us. Who can do that?"

Some names have been changed for security reasons.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].