ANALYSIS: Threat of war hangs over Kurdish independence vote

In a region already mired in a complex web of crises and conflicts, the prospect of independence for Iraqi Kurdistan looks set to add another layer of complication, following the recent announcement that a referendum will be held in September.

Though the announcement has provoked scorn from the expected sources, the primary fear among observers of the region is that contested Kurdish areas of Iraq could explode into violence, including intra-Kurdish fighting.

Interviewed in Foreign Policy last week, Massoud Barzani - president of the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) and leader of the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) - outlined his rationale behind calling the referendum.

"A long time ago I reached this conclusion that it was necessary to hold a referendum and let our people decide, and for a long time I have held the belief that Baghdad is not accepting real, meaningful partnership with us," he said.

"We don’t want to accept being their subordinate. This is in order to prevent a bigger problem, to prevent a bloody war, and the deterioration of the security of the whole region.

"That’s why we want to have this referendum - to ask our people what they want."

He added that the new referendum, unlike one held in 2005 following the formal recognition of the KRG by the Iraqi government, would be binding.

"The referendum in 2005 was arranged and campaigned for by civil society organizations," he explained. "This one is formal and held by the government and political parties.

"This one is binding and the other was not."

But the inclusion of a number of highly disputed territories in the referendum - particularly Sinjar and Kirkuk - has raised fears of further conflict even after the expected imminent defeat of the Islamic State group in Mosul.

"They [KRG] would fight for Kirkuk certainly, and probably Sinjar as well," David M Witty, analyst and former US Army Special Forces Colonel, told Middle East Eye.

The Iraqi forces are just worn out - on paper they should win, but in reality, probably not

- David M Witty, analyst

"But let's hope not. Then again, if KRG leaves and takes Kirkuk, we have all these Popular Mobilisation Unit (PMU) guys who say they are not disbanding," he added, referring to controversial Shia paramilitaries stationed across areas of Iraq liberated from IS.

If it came to military conflict in either Sinjar, Kirkuk or the other contested areas of Makhmour and Khanaqin, the outcome is far from certain.

In military terms, the Iraqi army has been severely depleted by the fight against IS. Should it come to violence between the KRG and the Iraqi government, the army will face difficulties.

"I think the Peshmerga would probably prevail," said Witty. "The Iraqi forces are just worn out - on paper they should win, but in reality, probably not."

'Illegal' referendum

The referendum was contentious from the beginning - the second largest party in the KRG parliament, the Gorran movement, described it as "illegal" and, during talks held to determine the process of holding it, Gorran and the smaller Kurdistan Islamic Group refused to take part.

"Gorran considers the independence referendum illegal because we believe this issue is a sensitive and important issue and affects everyone in the region and the new generation," said Shorsh Haji, the spokesperson for Gorran, speaking to Middle East Eye.

"Therefore it must be conducted as part of a law, decision or directive by the Kurdistan Parliament and not by some political parties and the KRG president whose position and the legality of his term is under question."

The Kurdistan parliament has not met since 2015 when the speaker Yusuf Mohammed Sadiq (a Gorran member) was prevented from entering Erbil by Barzani’s forces - a move that came in response to accusations by the KDP that Gorran had fomented riots against its party offices.

Kurdish civil war

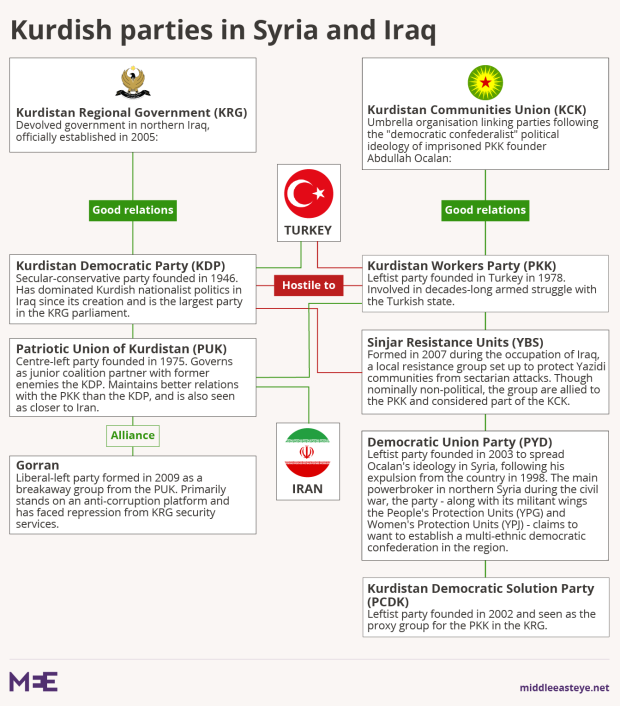

In the mid- to late 1990s, clashes between various Kurdish groups claimed thousands of lives. The fighting – which saw external powers back different groups – mainly pitted Barzani’s KDP party against Jalal Talabani’s PUK party.

A peace deal, brokered by the US, was signed in 1998.

On Tuesday, the KDP and the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK) - the third largest KRG party from which Gorran split in 2009 - attempted to reach a settlement which would see the parliament reactivated. But Gorran rejected the deal, as it would see Sadiq ejected from his position as speaker after only one session.

Haji said that his party was concerned that Barzani was using the referendum as a means for him to maintain his hold on power in the country, despite his mandate having expired in 2015.

He suggested that Barzani would use the referendum as a "negotiation card to gain personal and party benefits from Baghdad" and that he would use it to "portray himself as a national hero.

"His party supporters may be asked to demonstrate on the streets and call for him to run for presidency again despite the fact that according to presidential law he is not allowed to run for third or fourth run."

The date of the referendum is also set to take place shortly before scheduled parliamentary elections in November, a move analysts have suggested was intentional.

"I think holding the referendum a few months before the parliamentary elections is a way of changing the subject and building support among the nationalist base of the KDP," said Nate Rabkin, managing editor of Inside Iraqi Politics.

The likely focus on the referendum would deflect from "these questions about governance and reform which Gorran would like to see at the forefront of the election campaign."

For the first time maybe ever it seems like Kurdistan is a more valuable friend for outside powers than Baghdad

- Nate Rabkin, analyst

Since 2014, Kurdish politics has been heavily focused on the threat of IS, whose advance has seen a region once hailed as the "new Dubai" plunged into economic insecurity and the emergence of new social tensions.

But the image of a relatively secular, mixed-gender fighting force clashing with IS and holding it back from Iraq's borders has also built up the image of Iraqi Kurdistan in much of the world.

"There’s this sense among people in Iraqi Kurdistan and especially among people close to Barzani that the time is right to capitalise on the goodwill the Iraqi Kurds have built up by their participation in the fight against IS," explained Rabkin, speaking to MEE.

"This is a moment when there’s a lot of international sympathy for Kurds and where for the first time maybe ever it seems like Kurdistan is a more valuable friend for outside powers than Baghdad."

Contested areas

The major difficulty, however, apart from the logistics of detaching oil-rich Kurdistan from Baghdad’s already somewhat limited control - a move Iraqi Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi has dismissed as "illegal" - is determining the borders of the future state.

A tweet from Hemim Hawrami, assistant to Barzani, confirmed that a number of highly controversial regions would be included in the vote:

Gaining control of any of these areas is likely to be fraught with difficulty.

Kirkuk, which has been heavily dominated by KRG Peshmerga forces since they drove out the Islamic State group in 2014, is regarded as the cultural capital of a future Kurdistan by Kurdish nationalists - but its ethnic make-up is a mixture of Turkmens, Kurds and Arabs, all of whom contest its status.

Attempts to raise the flag of Kurdistan on government buildings have sparked angry demonstrations, while Peshmerga forces loyal to the PUK, the third biggest party in the KRG parliament, have entered oil-processing plants with the symbolic aim of wresting power away from the Baghdad government.

Sinjar flashpoint

Sinjar is potentially even more volatile - an affiliate of the Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK), which is ideologically opposed to the KRG, currently dominates much of the province. The Sinjar Resistance Units (YBS) have repeatedly clashed with Peshmerga forces loyal to the KRG and have warned against attempts by the KRG to assert its control.

To make matters even more complicated, Turkey has repeatedly threatened a ground incursion against the pro-PKK forces in Sinjar, while the Baghdad and Iran-backed Popular Mobilisation Units (PMUs) have promised to come to the aid of the YBS against the KRG and have sent forces into south Sinjar.

Another Kurdish majority region, Khanaqin, is currently part of Diyala governorate and not under the aegis of the KRG, while Makhmour has a large presence of pro-PKK forces.

With all this considered, there is unlikely to be any kind of smooth transfer of power should the referendum be in favour of independence - which it is expected to be.

Rabkin said he suspected the phrasing of the referendum question was intended the maximize the potential demands for the new state.

"Because of the way it’s phrased the question is ‘do you want’, and I think that actually leaves a certain amount of wiggle room for Kurdish authorities to negotiate another agreement short of taking all the disputed territories," he explained.

But any concessions are also likely to risk undermining both the integrity of the historically accepted notion of Kurdistan and Barzani’s stature, at a time when his authority has already been under serious scrutiny.

As such, conflict between Baghdad and Erbil - not to mention the numerous other factions with their own competing interests - starts to look increasingly likely.

"I think it definitely raises the risk of violence in the disputed territories but I don't think it necessarily means that things have to go in a violent way," said Rabkin.

"I think that both the KRG and Baghdad and many of the Shia PMU leaders would much prefer to avoid any violent clashes there."

"But given the past rhetoric on both sides and the passions this enflames and of course just how many different armed groups you have acting there, especially on the pro-government side, I think there's a real potential for a miscalculation or a misunderstanding, leading to ugly violence in one or more of these areas."

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].