Presidency, parliament and party: the future of Turkish politics

ISTANBUL, Turkey - A year after Turkey voted to leave behind decades of parliamentary politics for a presidential system, citizens have again found themselves preparing for an election with implications that go far beyond choosing their next leader.

Recep Tayyip Erdogan has remained the favourite to keep the presidency but opponents and analysts have highlighted the importance of simultaneous parliamentary elections on Sunday, which could define the extent of Erdogan's executive power and even the future of his Justice and Development Party (AKP).

The imposing banners fluttering over Turkey's roads make that significance clear; Erdogan's face alongside the AKP logo and an "Evet" ballot stamp, signifying the "yes" vote made by 51 percent of Turks taking part in last year's referendum on the presidential system.

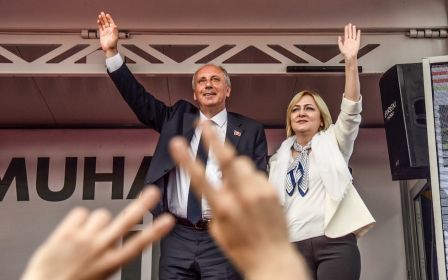

Polls indicate an Erdogan victory against his rival Muharrem Ince; predictions are mixed as to whether the AKP in coalition with their former opponents, Nationalist Movement Party (MHP), will secure a majority in parliament.

The executive presidency that will begin after the 24 June election will abolish the prime minister's office, transfer the role of drafting the budget from parliament to the president, and give greater control over the civil service. While an opposition parliament may be able to block some laws, the president could bypass it with executive decrees.

Turkey's opposition parties with often conflicting ideologies have formed an alliance to oppose Erdogan and the AKP, and while questions remain over their ability to work together, they are united by their shared rejection of the presidential system in the 2016 referendum.

[The opposition] have to be realistic, democratic, tolerant

- Umit Kivanc, journalist

How far they would go towards reversing the changes is unclear. Republican People's Party (CHP) lawmaker Aykut Erdogu told MEE an opposition majority would be measured in its response to avoid Erdogan accusing them of going against popular votes.

"We won't go back to the old parliamentary system, and we won't go with this authoritarian system. We will build a new segregation of powers better than the old system," said Erdogdu.

Leftist journalist Umit Kivanc believes any changes would hinge on whether parties can work together despite past hostilities, questioning whether the secular CHP can co-operate with the religiously rooted Saadet Party or whether the nationalist Iyi Party and Kurdish People’s Democratic Movement can tolerate each other.

"If they want to do something together, they have to be realistic, democratic, tolerant," said Kivanc.

AKP's future

For a brief moment at the beginning of the campaign, there appeared a strong chance that former president Abdullah Gul, who helped form the AKP along with Erdogan, would run against his former ally in the presidential race.

Gul stepped aside, returning to his marginal role in Turkish politics alongside other key AKP figures like former Prime Minister Ahmet Davutoglu and economic head Ali Babacan.

Some commentators believe that losing a majority in parliament could see an internal review of the AKP's unconditional support of Erdogan, which has seen him emerge as the party's sole leading figure.

"The team he started his political career with - very few of them are together with him right now," said conservative political commentator Izzet Akyol.

Erdogan will have no problem reigning in enough democratic support

- Sadik Unay, Daily Sabah

"The opposition, I assume, will come out of the AK Party again. There are so many people seeing all the eggs are in one basket. [There is] no party any more, there is only one person. He orders, other people obey."

Kivanc had a stronger view of the AKP’s future, claiming it could completely disintegrate because of the focus on Erdogan and potentially be replaced with another right-wing conservative party after having a radical impact on Turkish politics.

"AKP was the first political party in the mainstream scene in Turkey. CHP is not a political party; it's a party-like organisation which at the same time is a part of the state. MHP is directly a state organisation," he said. "If they lose, there will be no AKP for two years."

For Erdogan's supporters, however, there is confidence that the presidential system will deliver for Turkey, a country they felt has in the past been held back by dysfunctional parliamentary coalitions.

"These are historic days for Turkish democracy as the country braces for a paradigmatic transition toward a leaner, more efficient and productive mode of public governance via the presidential system," wrote Sadik Unay, a politics professor at Istanbul University, in the pro-government Daily Sabah.

"As 'the master' of great election victories, Erdogan will have no problem reining in enough democratic support for the new presidential government system," he wrote.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].