Standing firm or faltering? Erdogan's core voters play key role in elections

ISTANBUL, Turkey - With the sun setting beyond the many minarets of Istanbul's iconic Sultanahmet mosque and the thousands of people gathered nearby laying out their food to end a day of fasting, a van plastered with the Turkish president's face rolled into the public square.

Those nightly gatherings of religious Istanbulites were a brief, and natural, window of opportunity for President Recep Tayyip Erdogan to reach out to his core constituency in a month when Ramadan fasting had otherwise dulled the energy around campaigning for the critical presidential and parliamentary elections on 24 June.

Once communal meals were consumed and the crowd was rejuvenated, the campaign vans blared a medley of songs centred on the same lyric – Erdogan's name. The audience responded enthusiastically, dancing in circles, hoisting children onto shoulders and waving flags emblazoned with the lightbulb symbol of Erdogan's Justice and Development Party (AKP).

Maintaining that enthusiasm has helped Erdogan through 16 years of electoral dominance, but whether he can continue to keep his religious, conservative core engaged has become an increasingly urgent question as initial convictions about an instant Erdogan victory and the AKP holding onto its parliamentary majority have become increasingly shaken.

Much of that relies on the Saadet party, a strand of the same conservative religious movement the AKP emerged from but with which it is now at odds. But it has also come from the secular nationalist CHP, which has promised to move past old antagonisms while candidate Muharrem Ince has sought to play up his religious credentials.

According to Murat Gezici, co-owner of one of Turkey's top polling companies, there are signs the AKP vote is dwindling - almost a third of those it polled who voted for the party in the past would not talk about their voting intentions or said they were undecided.

"This is a sign of change. Erdogan and AKP voters used to be very eager to declare who they wanted to vote for," said Gezici.

While the AKP once easily secured controlling majorities in parliament on its own, polls by Gezici and others show it failing to get a majority or scraping through to that goal, despite a new alliance with the Nationalist Movement Party (MHP).

The issue for those voters, according to political commentator and businessman Izzet Akyol, is that they find little that is attractive about the opposition.

"I don't think the opposition is offering Turkey a better alternative," said Akyol, who himself voted for Erdogan until recently.

It's just one side against another and I won't support the AKP side

- Ali Osman Er, former AKP voter

"I have stopped supporting him but right now there is no alternative to support. I'm planning to vote for Saadet party, but actually I'm not a fan of them. They support Iran and Syria, they have a pro-Assad position.

"Still, I'm going to vote for them. Not to give them the power to govern the country but just to show my reaction to AK Party. Just to protest."

Other former AKP voters share that sentiment. They remain unconvinced by the opposition but are keen to register their disapproval.

"By voting Erdogan, we got better services. I admired his work, so I voted for him, but when someone stays in power 15, 20 years, it changes," said Ali Osman Er outside a shop in Istanbul's Bagcilar suburb, where he also complained about the financial struggles many voters were facing.

According to Akyol, many of Turkey's religious voters still resent the secular CHP for policies they felt discriminated against them, including a ban on women wearing headscarves in public spaces that was overturned by the AKP government.

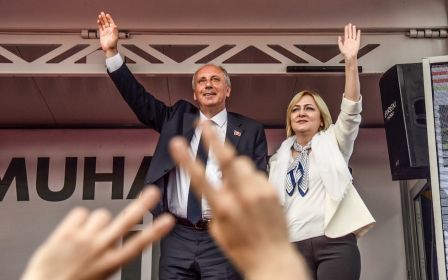

The CHP has tried to address those concerns, promising not to repeat "past mistakes". Ince meanwhile has played up his religious credentials by talking about teaching in an Islamic school early on in his career. He also criticised Erdogan's tendency to use rhetoric against Israel during election campaigns, accusing the president of also doing "secret deals" with the country.

The success of Ince's messaging for AKP voters appears limited. While some polls predict Erdogan failing to win the presidency in the first round of voting, most have him winning comfortably in a second round run-off against Ince.

Some of Erdogan's supporters also find Ince's showmanship aggressive, despite the president often being criticised himself for the strong language he has used against opponents.

"Muharrem Ince also has his mistakes, he behaves like a charlatan. I don't find him sincere," said Murat Gozler, a retired factory worker. "It might not be rational. It's emotional. I don't connect with him."

"There are some people, mostly educated people living in big cities, having strong Islamic values, like me. But what is the percentage of these people? I'm afraid not so many," he said. "But they are influential people: writers, academics, businessmen. This is gradually affecting other segments of society as well. But this is taking time."

In smaller cities and for those with more simpler concerns, he said, their votes will most likely be about the stabilities Erdogan has offered: better services and infrastructure.

That is the case for Gozler, who now spends his days fishing in Istanbul's central Karakoy district. His support is not unconditional, but while he dislikes the idea of Erdogan having complete control over Turkish politics, he feels those fears are exaggerated, especially in comparison to some of Turkey's advances.

"Turkey's suffered a lot with anarchy and political struggles. We used to have money in our hands but couldn't buy anything because there were shortages. Today is better," said Gozler.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].