'Years as a wanderer': 40,000 Libyans barred from going home

TUNIS - Militias and civil authorities from the city of Misrata are preventing 40,000 displaced residents from the town of Tawergha from returning home, blockading the main highway with burning tyres, firing shots and forcing families into a squalid tent town that has sprung up hastily down the road.

The three-week-long blockade is in violation of a hard-negotiated agreement by Libya’s UN-backed Government of National Accord (GNA), which makes special provisions for Tawerghans to return safely to their abandoned houses this month.

This is a terrible thing to do. My children are asking me, asking me all the time, why is this happening? When can we go home?

- Mahmoud Shahed al-Ashour, former Tawergha resident

It is the latest episode in a seven-year tale of intense hatred between two cities that fought on opposite sides in the opening salvos of the Libyan Civil War.

Strategically located along the route from Muammar Gaddafi’s hometown of Sirte and 260km east of Tripoli, Tawergha served as a staging ground for attacks by forces supportive of the late ruler against besieged Misrata, which was one the largest rebel enclaves during the 2011 civil war.

Explaining the militants’ actions to prohibit Tawerghans from returning home, the Misrata Military Council – an umbrella group of local militias - released a statement on 1 February accusing them of failing to fulfill their side of an agreement negotiated in 2016 by making unfriendly declarations and conspiring with rival militias in eastern Libya – charges that Tawerghan residents vehemently deny.

MEE contacted the council for further comment, but it did not respond ahead of publication.

Former government employee Mahmoud Shahed al-Ashour expressed anger about the blockade as his seven children chattered noisily around him.

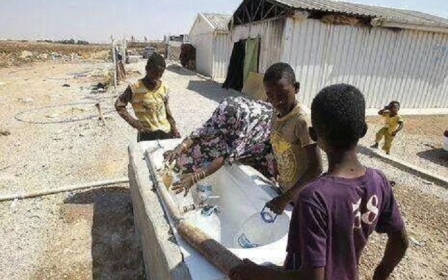

After travelling 500km west from their temporary refuge in Ajdabiya in the hopes of returning home, Ashour's family sits stranded with about 200 other families beside the dusty highway in Qararet el-Qatef camp, half an hour from the smouldering tyre blockades.

“Now, I’m just angry. This is a terrible thing to do. My children are asking me, asking me all the time, why is this happening? When can we go home?”

Seven years of exile

The Tawerghans have been wandering for so long, many kids in the camp are not old enough to remember home.

For seven years, the sun-baked brick facades of their city have gazed out silently over a desert highway 10km south of Misrata.

In Misrata, residents allege that Tawerghans serving in the national army led the three-month siege of their city and perpetrated atrocities against locals. Locals told journalists that Tawerghans raped women and castrated captured men.

These memories engendered a bitter hatred among the militias of Misrata and, as Gaddafi’s power crumbled over that summer, it was one that they would soon pay back in kind.

Tawergha local council member Emad Ergeha described the events of 11 August 2011, the day their exile began.

“We knew it was coming. That previous night the shelling erupted everywhere around us,” he recalled. “The electricity was cut, and the clashes kept drawing nearer.”

That morning, an armed brigade from Misrata began advancing down the dusty road to burn, ransack and punish the Tawerghans.

Warned of their approach, the remaining residents frantically scrambled to pack their bags and tumble out their front doors, leaving the city largely empty as militants entered the gates.

In the mayhem that ensued, three caravans set out; one rolling west toward Tripoli, one to the east, and one heading south, absconding deeper into the Sahara.

So residents began a seven-year odyssey of suffering and exile, dispersing Tawerghans across Libya into a network of cities and precarious displacement camps.

Hanan Salah of Human Rights Watch said civilians were left vulnerable by the nearly ubiquitous control Misrata militiamen exerted over checkpoints along the road to Tripoli until 2014, leaving them at the mercy of their tormentors.

Militants frequently entered camps of the displaced outside of Tripoli, shooting rifles into the air and rounding up any men who looked old enough to carry a weapon. Hundreds of Tawerghans were also arbitrarily detained, tortured, or simply disappeared on their way to attend to affairs in Misrata, she said.

“Given that Tawergha became uninhabitable, many had to go to Misrata just to obtain a copy of the civil registry if they wanted to get married or needed to bury someone,” said Salah. “All of these daily tasks became almost impossible.”

An unfinished peace process

While local efforts at reconciliation between the two communities started almost immediately after the expulsion, newly empowered Misratan militias saw little reason to accede to demands of their broken neighbours.

By December 2015, the moribund peace process was taken up by the UN Support Mission in Libya, which kick-started a more serious phase in negotiations between all parties in Tunis. The long and laborious talks aimed at returning civilians to their homes was brokered by the United Nations Libya mission, bringing together local officials from both communities in an effort to cease hostilities.

After inching forward for months, in August 2016, both sides signed an agreement giving $348m in damage payments to residents in both cities and paving the way for a Tawergha homecoming the following year.

Even after the negotiations ceased, Misratan militias agitated periodically for larger financial payments, delaying action by the government in Tripoli for months. Still, on June 2017, the GNA ratified the accord, paying out initial sums of the financial settlement and announcing February as the long-anticipated date of return.

But the initial euphoria of the Tawerghan diaspora quickly faded as thousands of returnees from all corners of Libya undertook the arduous journey home on 1 February, only to come face-to-face with a hostile blockade thrown up across their path barely a dozen kilometres from their destination. Forced into a hasty retreat, returnees fled back along the road they had just travelled, a tent city rising overnight on the formerly barren ground.

Salah confirms that civilians in the area lack protection from an armed militia and at present are at the mercy of the powerful Misratan forces. She says that while GNA officials, including Prime Minister Fayez el-Sarraj, have condemned the actions of these militias, they have taken no steps on the ground to protect Tawerghans in the camps.

For now, residents wait in limbo, hoping that something beyond their control will change and end their estrangement from their old lives – a scenario that at the moment looks unlikely.

“There’s no reason to foresee any major change for the people of Qararat,” said Salah. “At the political level it’s a stalemate. The negotiating committee from Misrata has insisted they return to the negotiating table, to renegotiate what they already agreed to. They went back on their commitment.”

Al-Ashour and his family, undeterred, vow to remain where they are until the militias move aside and allow them safe passage to the home they have been so long denied.

“Tawergha is my home,” he said. “I want to see my sweet city again, to rediscover my life as it was and end these years as a wanderer. That is the only place where we belong.”

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].