'I'm actually a doctor': Libyan vigilantes fight crime in lawless city

ZUWARA, Libya - “Come on, come on, come on.” Dressed in all black, a group of masked figures push two men into the back of a pickup truck.

Working from a secluded warehouse, the self-appointed anti-crime unit has been targeting criminals - from druglords to people smugglers - for five years in this coastal city left to its own devices as the Libyan state fell apart around it.

As one man is pushed into the truck, another gets a pat down from one of the masked vigilantes. The men, caught in possession of large quantities of hashish, are taken away to the abandoned warehouse, which doubles as a makeshift prison.

This is what one of dozens of raids orchestrated by the group looks like. Since they started patrolling the city in 2013, the vigilantes have siezed large quantities of drugs, weapons and other contraband.

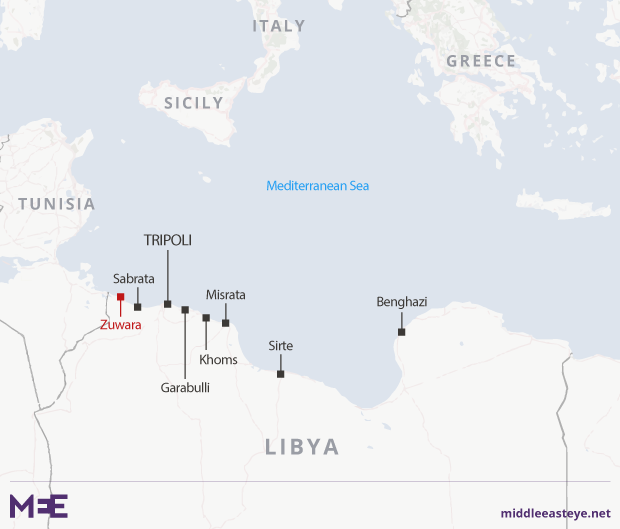

Though Zuwara was far from a crime-free zone before the 2011 uprising, things certainly deteriorated since.

Following the revolution, people-smugglers took advantage of lawlessless in the country, turning the once serene shores into a departure point for many migrant boats headed to Europe. Suddenly corpses of migrants and refugees became a common sight on the city's iconic white sands.

We sacrificed our careers in the hope that the next generation will have the chance to live better, and the country will improve

- co-founder of Zuwara Counter Crime Unit

At the same time, unrest also led to economic difficulties across the country, and many of the city's youth turned to fuel and petrol smuggling across the nearby border with Tunisia to make ends meet.

While residents opposed the people-smugglers' activities, local law enforcement didn't have the power to stop them. Local police officers would often avoid intervening in such crimes out of fear of how smugglers would retaliate.

With the rise in crime rates, the vigilantes felt there was no other option but to take matters into their own hands.

Officially known as the Zuwara Counter Crime Unit (CCU), but more commonly known by residents as the "Masked Men", members of the group have put their lives on hold for five years to "protect their community", as the volunteers put it.

The self-organised unit, formed less than two years after the overthrow of Gaddafi in the 2011 revolution, is made of a group of resident volunteers who aim to restore law and order in the city.

“We sacrificed our careers in the hope that the next generation will have the chance to live better, and the country will improve," one of the founding volunteers and the current chair of the group told Middle East Eye, speaking on condition of anonymity.

“After the revolution you could see there was no state. The rate of crime had increased, and in 2012, if things had stayed the way they were, we would have seen so many people killed in our city,” he said.

According to the chair, there were about 70 volunteers at the beginning. But now their ranks have risen to twice that number.

Zuwara was previously one of the key departure points for migrants heading to Europe from Libya, and a hub for human traffickers. Hundreds of people drowned after setting off from its beaches in small boats horrifically unsuited to crossing the Mediterranean, and the city's residents have buried 2,000 people that never made it to Europe.Since the CCU started operations against smugglers, however, the port town has seen a drastic drop in departures from its shores, something residents are mostly very happy about.

After the revolution it was like they [smugglers] knew no one would hold them to account whilst the country had no stable government

- Malak, single mother from Zuwara

“It was so shameful to know that we had smugglers in our city," Malak, a single mother who lives in Zuwara with her three children, told MEE.

"These people were around during Gaddafi’s time, but after the revolution it was like they knew no one would hold them to account whilst the country had no stable government.

“But they were wrong,” Malak added. “We held them to account, and these brave young men [CCU volunteers] are the ones that made sure they stopped.”

Though the group originally planned to work for six months, five years later it is still together, manning checkpoints into the city and offering its support to the border control authorities.

When the group was first set up, the volunteers all wore face covers to mask their identities, gaining them their local title. While many of those involved in the group are now known to locals, many still prefer to keep their identities hidden.

At first the men worried about criminals seeking retribution and feared for the safety for their families, but soon after their anti-crime activities began, they gained widespread support from residents.

Loosely affiliated to government counter-crime initiatives, the volunteers are a mix of former policemen, doctors, teachers and other civilians, with one thing in common: a desire to keep their city safe.

The group’s work includes combating robbery, drugs and weapons trafficking, vandalism and other nuisances. Over time human trafficking became a priority, as the body count began to mount.

After a few months, it became common knowledge in the city that if you were involved in any of these illicit activities, you would likely be arrested by the men in masks.

We faced many challenges. We would surrender them to prosecution and the next day we would find that they had paid their way out

- chair of the CCU

“If anyone was causing trouble, for example if they were caught with weapons without a permit, or caught with drugs, they’d be picked up," Hadi, a university student in the city, told MEE. "People started to know that if they fired weapons they’d be arrested and have their weapons confiscated.”

But when the masked men turned their attention to people-smugglers, it became a lot more challenging, according to the CCU chair.

“It was combating smuggling that was the real problem,” he said. “We faced many challenges. We would surrender them to prosecution and the next day we would find that they had paid their way out [of jail], so we couldn’t keep doing the same thing over and over.”

Big-shot smugglers

Wealthy and well-connected, people-smugglers proved their greatest test by date.

"When we started getting into things that would affect these big-shot smugglers, that's when it became very dangerous," the CCU chair said. Suddenly the criminals were leaving their own mark on the masked men.

“There are volunteers who really have sacrificed themselves. There are those who’ve lost their sight, or lost a limb from attacks against the group,” another CCU volunteer told MEE, adding that the state did nothing to help them.

And with the local police's detention centres proving so unreliable, the masked men instead began using their own headquarters as temporary prisons.

Once used by a Chinese construction company - which fled Libya in 2011 - abandoned offices and storage spaces are now used as places to hold detainees, conduct operations from and monitor the seas for any migrant boats attempting to make the crossing.

The facility does not have the capacity to hold people for long periods of time, so the vigilantes say they keep those accused of crimes in custody for days or weeks at the most.

"In Zuwara we reached a point in which there wasn’t a single case of human trafficking in the city. And that was all achieved through our own personal effort, we had no help from the state," the volunteer said.

As unrest in the country has made enforcing the law all the more difficult, residents of Zuwara have, mostly, been thankful for the self-organised anti-crime unit. However the group has not always been well-loved.

It has faced criticism for the tactics it uses to discipline those that they catch committing crimes, with some family members of detainees claiming that their relatives were beaten by CCU volunteers and threatened with more violence if they were to be caught again.

“The CCU has taught a lot of these criminals a lesson,” Malak, the single mother, said. “We know they [people-smugglers] should be in a proper prison for what they have done to helpless African migrants, but it’s better that the masked men scare them into stopping than letting them pay their way out of prison.”

“These smugglers don’t care about the migrants’ lives,” Hadi, the student, said. “Honestly, it may not be the best way to deal with them, but they are more deserving of a beating than they are of being free to send women and children to horrible deaths."

However, despite the CCU's success at cutting crime and the overwhelming support it receives from Zuwara's residents, its volunteers have had to go for long periods of time without pay.

“It’s not sustainable,” the chair said. “These people have given up their jobs to do this work. And even during times when we did have funding, it was all coming from the local council, nothing from Tripoli."

“I’m actually a doctor,” the volunteer said.

“I want to go back and finish my studies, specialise… but we have found ourselves stuck with no one else to do the job.”

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].