Before and after: Satellite images reveal Egypt's Sinai bulldozed and barren after war

The ghost towns of Egypt’s northern Sinai appear, from above, as clusters of ashen grey patches pockmarking the landscape. Surrounding them are desolate olive groves, now abandoned by the residents they once sustained and scarred by the boorish tracks of military vehicles.

During more than five years of war between the Egyptian army and militants, the region has been mostly closed off to outsiders but satellite imagery shows how northern Sinai has been blighted by the incessant fighting; homes demolished, the environment destroyed and its land swallowed by forever spawning military bases and checkpoints.

Using these images and interviews with local residents, Middle East Eye has observed how, since 2013, the northern Sinai has become increasingly militarised and its population ever more scarce. Thousands have been driven out of Rafah, on the border with the Gaza Strip, and the towns of Sheikh Zuwayd and al-Arish

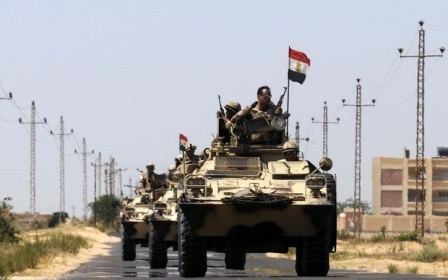

The Egyptian army’s battle has mostly been with local bedouin militants allied to IS, but its military operations have left the Sinai’s residents in the crossfire - they live under fear and curfew and more than 20,000 have been forced from their homes and land, according to Human Rights Watch.

While northern Sinai has seen an ever more obvious military presence during these years, the same time period has seen the worst violence against civilians. An attack on a mosque’s Sufi congregation killed more than 300 and the region’s Christian population fled because of the lack of protection.

The pattern in the images is of signs of life substituted for evidence of destruction.

Egypt's internal war

+ Show - HideIn 2013 the Egyptian army began a military operation against local militants, who later declared allegiance to IS, that has continued ever since.

Despite the operations, the militants have continued attacks against both official targets and local communities, including the Christian minority, but the northern Sinai's residents have remained caught in between.

The army began demolishing homes in 2013, claiming it was creating a buffer zone along the border with Gaza to stop arms smuggling, but Human Rights Watch has reported demolitions continuing into 2018.

Throughout 2018 residents were subject to a lockdown because of an army offensive against militants that meant restrictions on their movement and access to food, medicine and fuel.

“People wake up to birds or even to traffic horns but we in the Sinai wake up to bombings and sirens,” said a 28-year-old resident of Sheikh Zuwayd.

“From the Rafah border and as you go west, there are lots of demolished houses, burnt fields and empty buildings.”

“There is no Rafah anymore”

Human Rights Watch described Rafah as "completely demolished" by the military operation (Google Earth)

Once nestled on the border with Gaza, Rafah is now a town that has essentially disappeared.

Its homes have made way for a buffer zone Egypt has cleared next to the Palestinian enclave and satellite imagery shows how dramatic the change has been.

Intact in 2012, Rafah’s urban environment thins out during the course of the Egyptian military operation and by 2016 there is little sign the town once existed other than the chalky, barren scars its demolition left behind.

“We can say there is no Rafah any more. The city is completely demolished and 80,000 or 70,000 people who used to live in Rafah are reduced to hundreds of scattered people,” Amr Magdi, a researcher for Human Rights Watch, told MEE.

They began investigating the demolitions in 2015 after the government announced its plans to evacuate Rafah.

“The whole process was very abusive from the beginning,” said Magdi.

A junction on the road between Rafah and Sheikh Zuwayd transformed by road blocks (Google Earth)

According to their research, families were given little notice before the demolitions, inconsistently offered compensation that was often unfair and failed to provide the displaced residents with anywhere else to stay.

“We left our house in 2016. Our lives were turned upside down. Now we cannot plan six months ahead because we don’t know whether the houses we live in now will be demolished now or not,” a truck driver from Rafah told MEE.

“Everyone was displaced. No houses left. It became a ghost town. And even after that, the militants are still hiding there,” they said.

Checkpoints and military bases

Travellers in the Sinai compared the junction and checkpoint at Sheikh Zuwayd to a war zone (Google Earth)

Vehicles no longer dot the road from Rafah to al-Arish and the region’s towns now lie desolate. Travellers through northern Sinai instead describe passing dozens of checkpoints that transform journeys of hours into days.

The checkpoints are visible, many of them as sand berms dug away from the sides of the road, while in towns like Sheikh Zuwayd - at the epicentre of the fighting - the centre has been transformed.

The town’s central park has completely dried out and its main junction appears to have been evacuated of all movement, with two dirt barriers blocking all but a narrow passageway for vehicles coming from the direction of Rafah. A large object, which appears to be a military vehicle, blocks that passageway in most satellite captures from 2016 onwards.

The images are similar at other junctions along the road between Sheikh Zuwayd and Rafah, where any greenery has been dug away and flattened for military bases and checkpoints and slalom courses for oncoming vehicles have been built out of piles of sand dumped on the road.

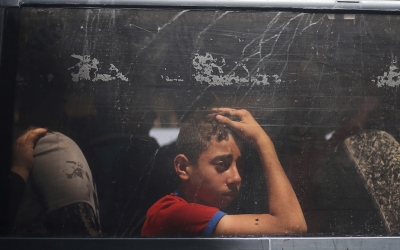

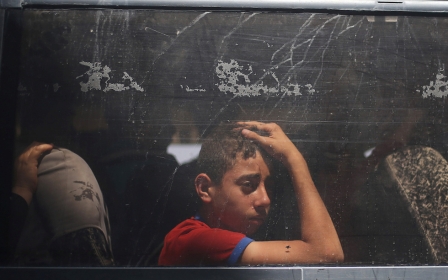

Palestinian traveller Mahmoud, whose name has been changed for his safety, told Middle East Eye that he was stopped at around 30 checkpoints on his journey from Gaza to Cairo, a route taken by thousands after the border to blockaded Gaza was opened in April last year.

At the first, their bus was stopped for four hours and its passengers made to sit on the pavement under the sun.

“It was like a war zone, soldiers everywhere [and] tanks,” he said of the landscape they found in the Sinai, even before they approached the checkpoint before Sheikh Zuwayd.

“It was the worst crossing ever. We were stopped because a lot of trucks carrying food and goods, petrol, oil were going to Gaza. Maybe more than 200. We waited for like three hours,” he said.

Away from the major junctions, the growth of military bases appears to have impacted on their surroundings. Not only has the land they occupy been razed but dirt tracks have formed where the military vehicles have repeatedly rumbled through.

In the wider area, the same ashen patches of demolished homes appear, more scattered than in Rafah but the displacement is clearly visible.

New structures appear during the military operation while land is damaged and homes demolished (Google Earth)

Human Rights Watch has called the military’s tactics “abusive” and “self-defeating.” Magdi told MEE that many of those displaced have had to live in temporary shacks built on agricultural land but which can end up being attacked by the military when mistaken for militant hideouts.

“The army is creating the problem and then further complicating the problem,” said Amr Magdi, a researcher for Human Rights Watch. “It shows how little respect the army has for the dignity of the people there.”

Another former Rafah resident, a truck driver, told MEE they were “lucky” to have had family who could shelter them.

“Some of the people in South Rafah are living in the rooms made of clay bricks or straw. Imagine in this cold, people are still living like this. The government said they will compensate, but we might die before getting anything.”

The environment devastated

The northern Sinai was once famed for its olive trees and the premium oil their crop produced but the war has ravaged production.

The North Sinai governorate plans to compensate the area’s farmers for at least 40,000 trees they can no longer access or that have been damaged, according to lists they published through Facebook, giving an indication of the amount of environmental damage done to the region.

The Sinai's bedouin residents rely on their land, which has been ravished by the military operation

“Agriculture needs stability and steady labour. Neither are available [now],” said the truck driver.

“After the Operation 2018 Sinai, a lot of land went bad. Afterwards no farming was allowed as the army was afraid these crops would go to the militants.”

The damage done to the land is the most dramatic and obvious change in the images provided by satellites. From a distance, vast swathes of land have become barren. Zoomed in, the detailed picture is of fertile land that seems to have died and trees that have completely disappeared.

“Most people I know sold their land. For the Bedouin, this is the worst. Selling your land affects your honour.”

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].