Algeria protests: This is what a revolution feels like

This piece will not attempt to analyse unfolding events in Algeria, nor to offer a euphoric celebration of them; rather, it will try to provide subjective testimony about these early moments of the country’s protest movement, as accumulated by the senses and memory.

On 22 February, anonymous calls for protest against President Abdelaziz Bouteflika’s bid for a fifth term streamed through social networks. A number of towns had already expressed their refusal to accept this umpteenth infringement on our dignity.

Breaking free

Algiers, which for years had been strangled by a state of emergency inherited from the Black Decade and a protest ban imposed by the government since 2001, finally appeared ready to lift the oppressive constraints of silence and inertia.

Virtual voices initially warned against the Islamist spectre, with a march set to occur after Friday prayers. Some were suspicious of the anonymity of the call, while others lined up with the indecisive stances of their parties.

Power, if it could be compared to a chronic disease, must ultimately be confronted by the shock therapy of disobedience

I knew I would be drawn there, and I was. Police seemed disoriented by the volatility of the situation. I imagined them getting contradictory orders as pressure points changed, continually moving around to follow the unpredictable movements of the divided crowds.

Protesters converged at different points, heading to scattered “targets”. They snuck from one neighbourhood to another, capitalising on the extreme effectiveness of disorganisation, the deconstruction of space and time.

‘No fifth term’

Earlier that morning, the oppressive state apparatus appeared to be more sure of itself, highly experienced at dispersing meetings by way of the truncheon. But in the afternoon, Algiers became a hive of activity - a labyrinth of voices and dancing feet on the cobblestone.

Fragments of sentences became slogans and songs: “Bouteflika, there will be no fifth term, even if you bring the intervention squad and the elite troops of the police force”; “This is a republic, not a monarchy”; “The people refuse Bouteflika and [his brother and adviser] Said”; “Peace to the Harragas’ [North African migrants’] souls.”

We reached Zighoud Youcef Boulevard, where a procession of young people - without a partisan flag - wove between the sea and state buildings, with riot police deployed on both sides of the road. A cordon of officers attempted to prevent us from marching further.

There was a joyous mood in the air - a rapture that increased with each kilometre crossed, as protesters exchanged knowing looks and smiles.

The desired victory remained hypothetical, but another obstacle had already been conquered: that of being able to occupy a formerly forbidden public space, and of saying “get out” to those who have long believed in their own invincibility.

A forbidden space

Power, if it could be compared to a chronic disease, must ultimately be confronted by the shock therapy of disobedience.

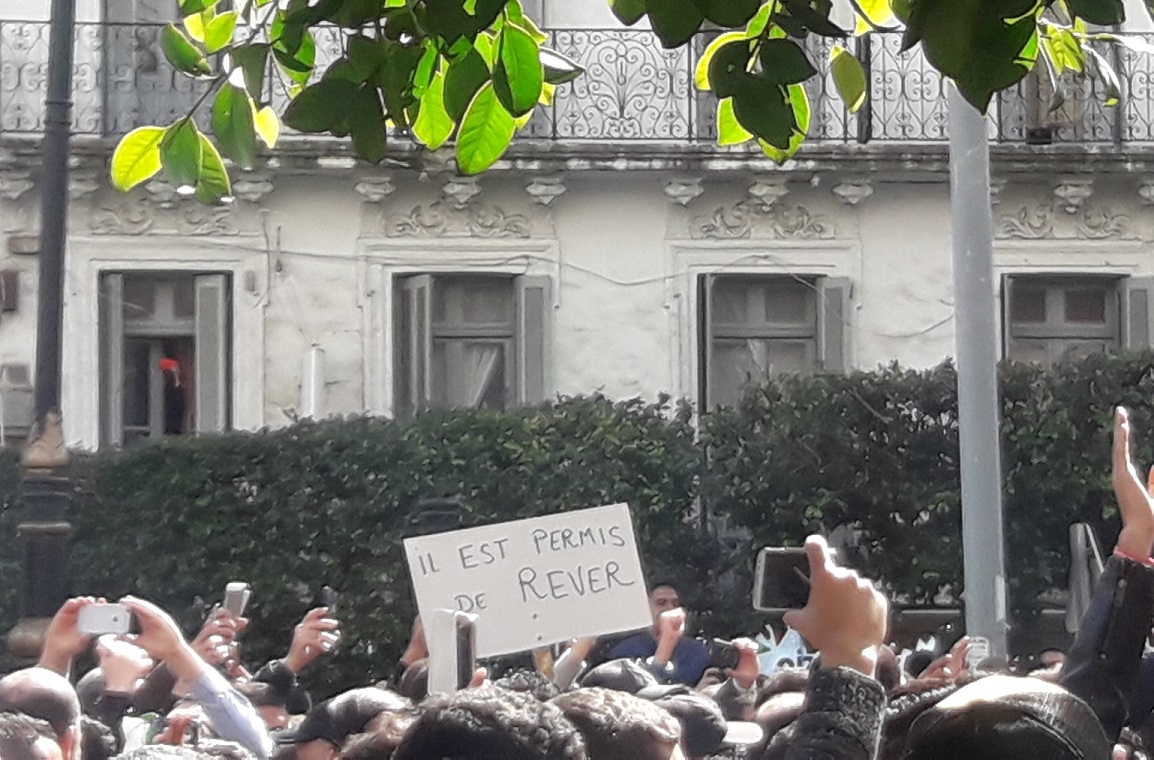

The impetus is as simple as a raised fist, as the crazy hope of a woman brandishing the picture of her disappeared son, “kidnapped by police in 1996 while he was only 16”; as this cordon of officers that yields to protesters’ advances. Beauty is here, because the street - a formerly forbidden, faded, impersonal, apolitical area - has become a huge dance floor again.

This movement - which entails scattering, immediately followed by uniting, and running back and forth between the main boulevard and the nearby streets to escape the authorities - is so much like choreography. The song is that of thousands of bodies brought back here, together, to launch a rebellion.

These thousands of individuals have been spurred on by dreams, by different convictions and beliefs, all the while targeting a shared enemy: a gerontocracy that danced for a long time upon the people's corpses, and sang all the possible ranges of disgrace.

Breaking point?

On 24 February, a meeting in central Algiers called for action by the recently born Mouwatana (“Citizens’ Democracy”) movement. I knew then that the “virus” of the street had taken over people’s minds.

While the movement’s leaders had been arrested, hundreds of young people and political activists aimed to strike up a discussion with the forces of order, some of whom appeared to hesitate between repression and fraternisation, even as undercover officers pushed for arrests. Tear gas made both protesters and police stagger; they used a form of vinegar to limit its effects.

There is, in the 22 February movement, the ambiguity and perils we find at the beginning of every revolution

The next day, students across the country screamed the pain of a generation that has grown up in an Algeria marred by corruption, authoritarianism, doublespeak and a life without colour.

So, how to decipher all of this? Have we reached the much-vaunted revolution threshold - the breaking point that arrives just when society’s resignation appears on the cusp of permanence?

Uncertain tomorrows

The regime has inflicted all kinds of arrogance and abuse upon the population. Yet, being aware of its legendary regenerative abilities, how can we not be concerned about the likelihood of sham “reforms” meant to calm the crowds - a joker pulled out of a hat to enable the continuance of the regime’s happy plundering?

How can we not consider the possibility that the Islamists, today made over as moderate and respectful of the republic, show up as usual to hijack the revolt?

There is, in the 22 February movement, the ambiguity and perils we find at the beginning of every revolution: the uncertain tomorrows, loaded with catastrophic scenarios, or caught up by reactionaries who could disfigure dreams and kill hopes. But as with any revolution, the will to live in the moment prevails over everything else.

This article originally appeared in the MEE French edition and was translated by Virginie Le Borgne.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].