How the UAE's stability narrative threatens change across region

It has been a dramatic few weeks in the Arab world with Algerian President Abdel-Aziz Bouteflika stepping down after 20 years in power, self-proclaimed General Khalifa Haftar deciding to move on the Libyan capital Tripoli, and Sudanese President Omar al-Bashir forced to resign after 30 years of rule.

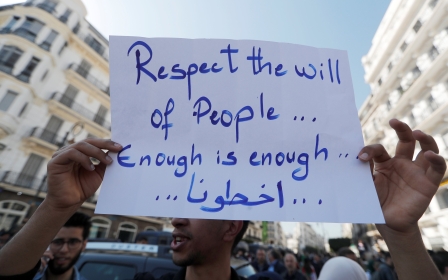

It seems that while Libya goes into the second round of its post-revolutionary civil war, in Algeria and Sudan the people have succeeded - so far - in having their demands met after months of protests that had already been dubbed "Arab Spring 2.0".

While developments in Algiers and Khartoum provide reasons for hope, the case of Haftar in Libya shows that the initial enthusiasm over the fall of the Gaddhafi's regime was premature.

The naive idealism of the early days of the Arab Spring gave way to widespread cynicism as some countries collapsed into civil war

In all three cases, the achievements and legacy of the protestors on the street are threatened by military organisations or strongmen whose ambitions for direct or indirect military rule could see the transition from one dictatorship to the next.

When the revolutions of 2011 were televised across the world, the images of protestors taking to the streets to decry social injustice and political oppression sparked liberal enthusiasm in the West.

The naïve idealism of the early days of the Arab Spring gave way to widespread cynicism as some countries collapsed into civil war while others, such as Egypt, transitioned into military dictatorship after a brief year of civilian rule under the Muslim Brotherhood.

Authoritarian stability

The military coup d’etat in Cairo in the summer of 2013, was indeed a turning point in the Arab Spring as the counterrevolutionaries under the slogan of "authoritarian stability" reasserted themselves.

With the exception of Tunisia, all revolutions either got stuck in atrocious civil wars or saw survivors of the ancien regimes assume power.

The architect of this counterrevolution sat in Abu Dhabi: Crown Prince Mohammed bin Zayed al Nahyan (MbZ), the de facto ruler of the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and mastermind behind Little Sparta's rise as an assertive military power in the region.

Plagued by regime insecurity paranoia, MbZ looked upon the emancipated civil society in the Arab world as a fundamental threat to national security – any victory for pluralistic, civilian rule in the region would be a defeat for the UAE’s model of military rule.

Any victory for pluralistic, civilian rule in the region would be a defeat for the UAE’s model of military rule

Abu Dhabi’s strategic narrative of "authoritarian stability" was built on the premise that socio-political pluralism leads to chaos under civilian rule.

This narrative was plugged into existing conservative fears in the West about a new socio-political status quo emerging that would bolster political Islam – the nemesis of neo-conservative Islamophobes the UAE has engaged with since 2014.

Egypt: A case study

The case study Abu Dhabi always presented was Egypt where the repressive clamp down on civil society following the military coup by President Abdel-Fattah el Sisi in 2013 was justified by a return to "order and stability" and the fight against "terrorism".

It made no mention of the fact that the UAE had played a strategic role in undermining civilian president Mohamed Morsi’s rule by creating a pretext the military could exploit.

The same narrative has been propagated by the UAE in promoting the rise of Haftar in Libya since 2014.

The rogue former CIA operative had returned to Libya amid a time of post-revolutionary consolidation to oust the elected parliament and cleanse the country of "terrorism" – a label used indiscriminately against any form of political opposition to his ambition to consolidate military rule.

Abu Dhabi and Cairo would provide financial, operational and material support to Haftar’s "Operation Dignity", giving his loose army of militias the operational edge against its opponents – not least because Haftar could count on combined Emirati and Egyptian air power.

No anti-status quo order

In Algeria – a country often dubbed a military with a state – the ongoing mass protests and departure of Bouteflika have created a window of opportunity for a peaceful transition to civilian rule.

But some see strongman Chief of Staff Abdel Gaid Salah as a potential obstacle who, wanting to secure the institutional and commercial interests of the military, opposes any anti-status quo order – something that the UAE welcomes.

Gaid Salah has been seen visiting the UAE multiple times since the protests broke out and has in recent years built an amicable relationship with Abu Dhabi’s leadership: both advocate a strong military as a guarantor of stability and both see Islamism as a strategic threat.

In Sudan, the military has taken control after months of violent protests, removing President Omar Bashir from power, and promising transition to civilian power only after a two-year transition period.

While Sudanese protestors are currently cheering the arrest of Bashir, the military hopes to secure the survival of its deep state for the long-run. After Defence Minister Ahmed Awad Ibn Awf did not survive the first 24 hours of his coup regime, the new transitional president, General Abdel Fattah Abdelrahman Burhan appears like the perfect military strongman for Abu Dhabi.

He has been a reliable partner for the UAE in the war in Yemen, and is one of the few Sudanese military leaders without any ties to the old Islamist guard.

Hence, the problem with the UAE’s narrative of "authoritarian stability" lies in its advocacy of military-based authoritarianism that undermines socio-political pluralism and clamps down on civil society in an attempt to reverse the achievements of the Arab Spring.

War over narratives

The danger of this narrative lies in its normalisation in the West, whereby UAE disinformation networks try to win over the hearts and minds of journalists, think tankers and policy makers to embrace a simplistic world view that plays into the hands of Islamophobes and Orientalists.

Abu Dhabi’s war over narratives in the information space has already borne fruit in the Libyan context, where France has embraced the narrative of "authoritarian stability" confronted with livestreamed Islamic State group (IS) executions on Europe’s doorstep.

Ever since, Paris has been eager to support Abu Dhabi’s warlord politically and militarily, hazarding the consequences of Haftar becoming the face of a military without a state.

The neo-cons in the Trump White House have equally bought into the same narrative.

The UAE’s military strongman in Egypt, Sisi, has been courted in Washington as a guarantor for stability by the administration during his recent visit. Again, the narrative of "authoritarian stability" is being embraced without any strategic consideration for the long-term consequences.

Sisi's regime has developed into a shining example of a military with a state that serves the few but not the many, thereby setting the disenfranchised but networked masses up for another revolution.

Despite the UAE's best efforts, the genie of popular revolution has been unleashed, demonstrating that no military authoritarian is immune to the aggregate power of individuals feeling alienated and disenfranchised by patrimonial dictators in uniform.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].