Algeria's paradox: To achieve democracy, citizens must reject July election

Holding a presidential election on 4 July and proclaiming the results the next day: this is a gift that the country is offering to its people on Algeria’'s independence anniversary.

The picture is splendid; it is a full-scale PR operation. This might have seemed a great move to bring the protests to an end, after the street sacked former president Abdelaziz Bouteflika, former prime minister Ahmed Ouyahia and other politicians.

Unfortunately for the country's new strongman, General Ahmed Gaid Salah, the stunt went wrong on the first Friday after Abdelkader Bensalah's appointment as interim president.

Out of the question

Gaid Salah advocated a constitutional approach by pushing Bouteflika out and replacing him with the Senate president, in accordance with Article 102 of the constitution. This was meant to allow the regime, represented by the famous three Bs (Bensalah, Prime Minister Noureddine Bedoui and former Constitutional Council president Tayeb Belaiz), to remain at the helm and smoothly arrange a presidential election for 4 July.

The street rejection was clear-cut. Holding a presidential election with the same politicians, institutions and mechanisms of the Bouteflika era is out of the question, protest leader Mustapha Bouchachi said.

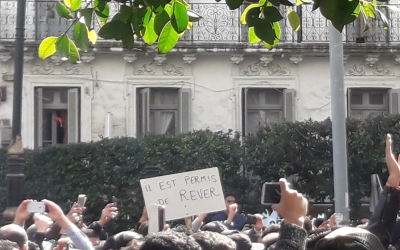

Energised by its successive achievements ... the street has rediscovered its power and started to dream. Algerians now believe in what once seemed impossible

Despite the escalating repression and mobility restrictions around Algiers, large-scale demonstrations on 12 April undermined the army's plan - and despite the authorities' tough response, the protests continued unabated.

Energised by its successive achievements - Bouteflika's departure, the scrapping of his fourth-term extension and the cancellation of the 18 April presidential election - the street has rediscovered its power and started to dream. Algerians now believe in what once seemed impossible.

Another week of major demonstrations could lead to the cancellation of the 4 July election. This seems easily achievable considering the current context, which is strongly in favour of the street.

Refusing to participate

The government, which no longer has any room to manoeuvre, has already lost the battle. Ministers are trapped in their offices; three of them, travelling to Bechar earlier in the month, were unable to carry out their agenda as locals blocked the roads.

The energy minister was unable to complete a modest visit to Tebessa in the east. In both cases, the government members had chosen to travel to supposedly low-risk regions.

Judges have opted to boycott the 4 July election, while dozens of mayors have also refused to participate in the process. This is not about to stop, with further actions expected in the days ahead. The upcoming presidential election already seems like an impossible feat.

These recent developments are thwarting the plans of the government, which had hoped to swiftly drag the country through an electoral cycle.

Only Ali Ghediri, a retired general who was already a candidate for the 18 April election, has announced his candidacy for the 4 July vote. Other potential candidates are wavering, unlike what was seen when the previous election was announced, as many politicians rushed to submit their candidacies.

Ali Benflis, a major contender in 2004 and 2014, has said he would not run for the presidency in the current political context.

Fear of disgrace

There is also little enthusiasm among political parties. The traditional organisations that were challenged by the protest movement were forced to express their support for the demonstrators in order to survive.

Parties are now afraid to rush towards the electoral path, for fear of being permanently disgraced.

All this leads to a conclusion that the 4 July presidential election will be impossible. No candidate will be able to campaign under normal conditions. The protesters won't let it happen.

If the government decides to hold the election, it will have to crack down harder, which may further discredit it and accelerate its demise. Moreover, a presidential election in this context will not be legitimate: the situation is unstable, and many credible potential candidates will boycott the vote.

It would be impossible for the newly elected president to manage the country afterwards, unless he was prepared to adopt a large-scale repressive approach - which would be implausible for the military, due to the army's support for demonstrators.

This would prompt the army to develop a new battle plan. Until now, the plan was to enforce Articles 7 and 8 of the constitution: The people are sovereign, and they exercise their sovereignty within existing institutions.

Disrupting traditional politics

This approach was to lead to a presidential election. The people are challenging this scenario, because they perceive it as a straightforward way for the army to regain control. But despite the scale of the protests, the street is not yet fully empowered, homogenous or structured enough to put forward a candidate against the regime.

The protesters want a transition to disrupt the traditional electoral pattern that will inevitably lead to the government's victory.

The Algerian street is rejecting a presidential election right now, because the country is not yet ready

While the vote is traditionally perceived as the ultimate outcome of democracy, the Algerian street is rejecting a presidential election right now, because the country is not yet ready.

The people want to change the country's political landscape, as a first step towards an election that will yield a different outcome than what the country has experienced for the past 25 years.

This is the paradox of the emerging new Algeria: its citizens have found out that in order to achieve democracy, they must first refuse to engage in unfair elections.

This article originally appeared in the MEE French edition.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].