'Silence is death': Algeria's journalists begin to find their voice

The Algerian journalist and writer Tahar Djaout once said that it was a tough job being Algerian.

Djaout was assassinated by the Armed Islamic Group in 1993 and during that dark decade his observation felt particularly true. Watching and writing about the terror inflicted upon the people of his nation, caught between the repressive Algerian regime and the Islamic Salvation Front (FIS), the outspoken author provided, in novels, journalism and poetry, a sensitive and enduring depiction of life in contemporary Algeria.

It was a particularly dangerous time for journalists, writers and news reporters, who were regularly threatened with their lives or assassinated. Djaout was the first to be killed in this way but many more would follow. Over 100 people who worked within the field were assassinated during the 1990s.

As we approach the anniversary of Djaout’s death on 26 May, Algerians are reminded that the repression he famously spoke out against - that he paid for with his life over two decades ago - continues today at the hands of the Algerian state.

A deplorable reputation

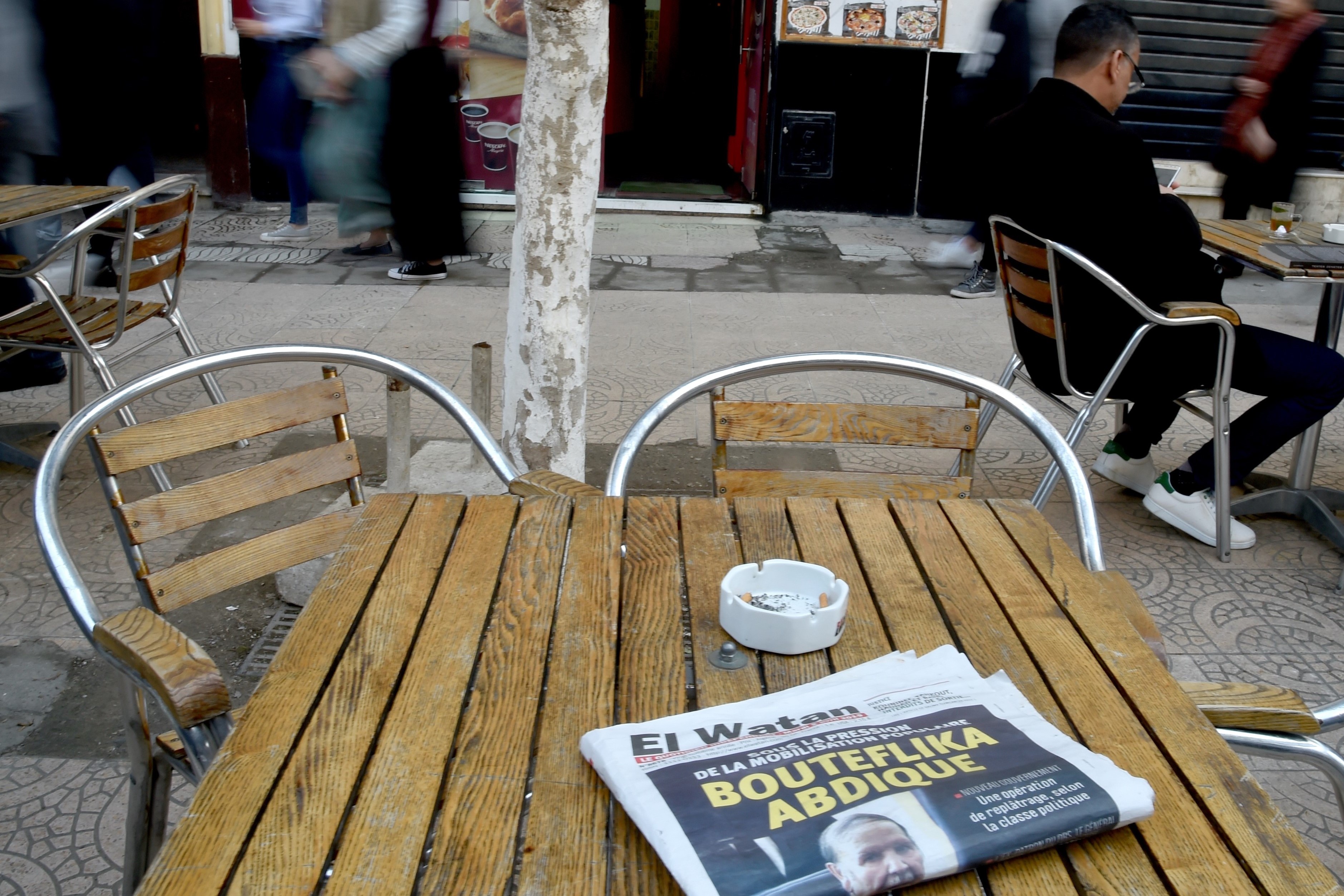

In the context of the ongoing revolution, and for the eleventh week in a row, journalists across Algeria have been staging sit-ins in Algiers demanding press freedom, democracy and an end to censorship.

Reporters Without Borders ranks the country 136th out of 180 countries in the World Press Freedom Index, and since the uprisings began on 22 February, it seems that the regime is keen to secure its deplorable reputation.

Journalists across Algeria have been staging sit-ins in Algiers demanding press freedom, democracy and an end to censorship

This caused suspicion, and mainly anger amongst protestors. Lynda Abbou, an Algiers- based journalist for Maghreb Emergent, told the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) that the population had started to turn on all those who worked in media. “When we show up, [protesters] ask us, 'Where were you on the 22nd?'" she added.

While on the outside it seemed that many journalists and presenters were complicit in the state’s silencing methods, dissenting members of the press spoke out about the censorship they had faced while attempting to cover the protests.

Slowly more and more journalists publicly complained about the muzzling "from above" and the direct orders that they were being given against reporting the uprising.

Speaking truth to power

Abderrezak Siah, a presenter who works for the national (state-owned) television channel A3, was removed from his post after he spoke out against the uncritical coverage of former president Abdelaziz Bouteflika and called for press freedom at the end of last month.

Siah stated that public television had become “the mouthpiece for corruption", adding that "our main mission is to provide a public service, and I call on all television journalists and young people from the protest movement to peacefully support our fight."

Other journalists were also sanctioned for supporting the movement. Melina Yacef’s show was pulled off the air, Ali Haddadou was reprimanded for a Facebook post that he had published and Imane Slimane was "re-deployed" over her support for the protests and press freedom via social media.

Abdelmadjid Benkaci, a reporter for the state-owned Canal Algerie, was subject to an official warning and said that his salary was also impacted because he had taken part in a televised debate on BRTV - a private Algerian channel - without asking his superiors for permission.

Benkaci said that his only crime was defending freedom of speech, and that this was why he was being targeted.

Canal Algerie news reporter Nadia Madassi says she was also sanctioned for supporting those who took to the streets every Friday demanding the fall of the regime, and subsequently resigned from her post in early March.

There are other cases like these.

The Panama papers factor

The problems with state censorship are nothing new, many of the long-standing journalists have been forced to endure years of official news directives, articles and shows being blocked because of their critical nature and the threat of or direct withdrawal of state advertising, which is the only source of funding for many newspapers.

In reality, the Algerian state has reason to be afraid of transparency and free reporting

Hadda Hazem, the first woman journalist to set up a newspaper in Algeria, faced such threats to her paper Al-Fadjr after criticising Bouteflika’s fourth mandate.

After 17-years, the paper was forced out of print and Hazem even went on hunger strike to protest the attacks on press liberties and freedom of speech.

In reality, the Algerian state has reason to be afraid of transparency and free reporting. For example, three years ago, over 11 million private documents were leaked about offshore financial entities.

These were known as the Panama Papers. Among the many businessmen and public figures who were outed from around the world were prominent Algerians, who have since found themselves in the eye of the revolutionary storm.

The papers highlighted the considerable amount of money found in offshore accounts. Given it is estimated that there has been a loss of billions of dollars to accounts abroad, this leaked document helped clarify where the country’s wealth was being taken.

The journalist Lyas Hallas told the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ) that the information shared on the level of corruption had “politically weakened ministers who were at the height of their power and others who were on the cusp of bouncing back.”

The Panama Papers were not necessarily a revelation for the Algerian people, who had long known that the regime and its friends were stealing the riches of their country and shipping it abroad, but they provided hard evidence for how this was being done.

The revolutionary struggle

Investigations, arrests, a massive international scandal and evidence for the masses who are now taking to the streets in their millions, naming those who have driven their nation into economic crisis and left the people poor and desperate, are just some of the outcomes of this report.

Think what more lies under the surface and how a body of journalists free to investigate and publish their findings could nourish the current revolutionary struggle.

The uprisings in the surrounding region back in 2011 were also an indicator for the Algerian state of the scale of damage that can be done to their rule by the rapid spread of information and sharing of lessons and tactics by demonstrators, which also encourages further media repression.

The Algerian regime may have learned from the counter-revolution during the Arab spring, but so did its people, who stood in solidarity with all those who marched, occupied, and died in the name of freedom.

During each demonstration for the last 13 weeks, there have been hours of internet blackout. It has become almost customary, but it has not discouraged those reporting. Videos will be filmed, quotes will be noted, scenes will be recorded, and the information is shared – and spread like wildfire – as connection is restored.

Growing pressure

During a protest action, journalists were also arrested and held for hours at the police station. But members of the press were not deterred from staging continued action every Monday for the right to "report freely".

The growing pressure from below has already been seen. Much more will be needed for real change to be achieved, but the people’s mobilisation is not relenting despite the regime’s repression.

Tahar Djaout put it powerfully and beautifully when he wrote: “Silence is death, and you, if you talk, you die, and if you remain silent, you die. So, speak out and die.”

Today, life has returned to the Algerian people who speak, write, and shout for the right to never have to endure silence again.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].