How ties with China bolster the UAE's bid for regional dominance

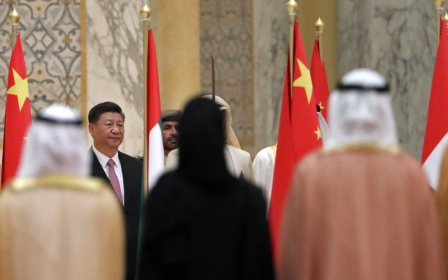

Abu Dhabi’s influential crown prince, Mohammed bin Zayed, embarked on yet another diplomatic crusade last month to win over Chinese President Xi Jinping, seeking to consolidate ties with a booming economic global powerhouse.

During his three-day visit to Beijing, bin Zayed and Xi discussed boosting strategic and economic ties. They agreed on greater investment and trade links, such as increased cooperation in the banking, oil, tourism and scientific sectors, which could add up to $70bn by the end of next year.

Bin Zayed also lauded what he called a “road map” for a century of prosperity between the UAE and China, suggesting ties could yet increase further.

A shining pearl

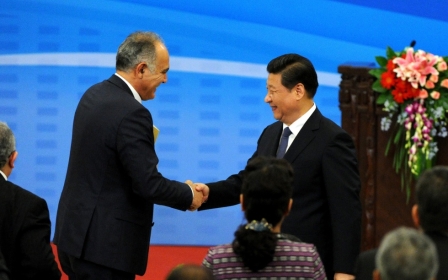

These developments are a fortification of existing ties. China and the UAE officially established diplomatic ties in 1984, and China’s investment in the UAE has increased markedly within the last decade, coinciding with both China’s economic expansion into the region, and the UAE’s rapid growth as a regional player.

Last year, leading figures from both countries proposed deepening economic ties and establishing a free-trade agreement. China sees the UAE as a shining pearl on its Belt and Road strategy for global development, with the UAE in April signing a deal with China that could see it acting as a vital land and sea trade hub for Beijing’s vision.

Both states have differing regional aspirations and strategies for securing their influence

On the agenda in July was the prospect for increased regional and international cooperation, laid out in 16 memoranda of understandings that also highlighted increased defence cooperation. Both Abu Dhabi and Beijing seek economic dominance, using their financial influence to become powerful forces across the Middle East and North Africa.

Admittedly, both states have differing regional aspirations and strategies for securing their influence. Abu Dhabi seeks to cooperate with and empower various authoritarian political actors, under the guise of security and humanitarianism. Unlike China, it would directly bear the political consequences of any democratic regime changes, which could prompt calls for reforms within the UAE itself.

Beijing, meanwhile, is less directly impacted by regional developments, and claims to prefer non-intervention in states’ domestic affairs, while offering development and infrastructure projects to disadvantaged countries. Consequentially, its investments have grown substantially in Africa and the Middle East in recent years.

Stability narrative

The UAE’s support of “stable” authoritarian regimes could benefit China. The UAE is also riding on China’s growing influence, siding with Beijing to further its own geostrategic regional ambitions.

To ensure that it has significant international backing, the UAE could drift towards China further. As a permanent member of the UN Security Council, China could grant the UAE additional impunity for its actions in Yemen, its support for Libyan warlord Khalifa Haftar’s assault on Tripoli and its other regional endeavours, such as in Sudan.

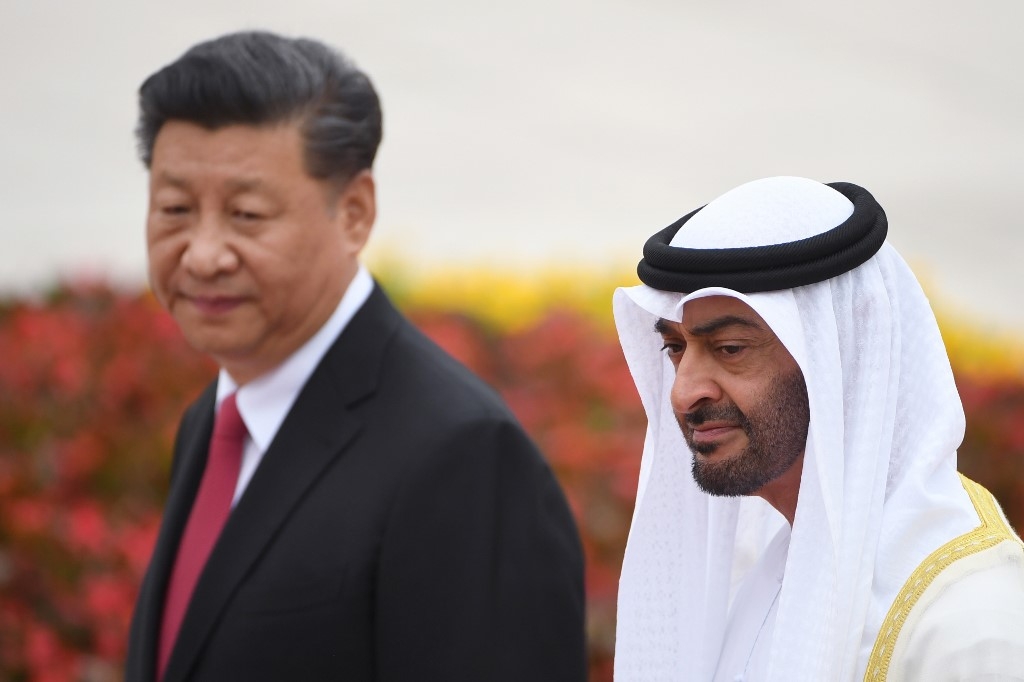

In last month’s meeting, Xi declared that “China backs the UAE’s commitment to regional peace and stability”. He also noted that China seeks an “oasis of security” in the region rather than a new “source of turmoil”. His words somewhat echo the UAE’s stability narrative, which Abu Dhabi adopts to justify supporting authoritarian, anti-democratic forces across the Middle East and North Africa.

China and the UAE could further cooperate to shore up regional political actors. Both may seek to rebuild Syria, war-torn since 2011 uprisings failed to topple President Bashar al-Assad. With the EU and US refusing to rebuild the destabilised country, and Assad’s allies, Russia and Iran, lacking the financial capabilities to take a leading role, questions have emerged over who can finance Syria’s infrastructure and development.

China and the UAE are tipped as potential candidates for this, particularly as the UAE reopened its embassy in Damascus last December. Ultimately, this would deliver a continuation of authoritarian rule in Syria. With the consolidation of the Assad regime, reformist hopes would diminish.

Blocking reform

In Sudan, the UAE and Saudi Arabia have sought to empower the transitional military council and block any hopes for reform. China could play a more assertive role by investing in any future Sudanese regime, while not particularly supporting either side - but at a time when the protesters need greater international support, this could lead to undermining their wishes. China and Russia recently refused to support a freeze on the planned shutdown of a peacekeeping mission in Sudan’s Darfur region.

China has also controversially backed a “re-education” programme for millions of Uighur Muslims, attracting widespread criticism from human rights groups, although countless countries have remained silent.

Using the pretext of counterterrorism to target the Uighurs, China’s policies somewhat match that of the UAE in its regional crackdown on the Muslim Brotherhood. The UAE has therefore supported China’s crackdown; Xi thanked the UAE for backing Beijing’s policies in Xinjiang, while Abu Dhabi’s crown prince said the UAE would be willing to “jointly strike against terrorist extremist forces” with China.

As with other countries’ support for China’s actions, Abu Dhabi is putting economic prosperity before moral values, as supporting the Uighur crackdown further guarantees Beijing’s economic ties and likely further support for its own regional agenda. As an influential Islamic state, this gives China a further green light to advance its re-education programme.

A new era?

One area that presents risks for the UAE-China relationship, however, is the Horn of Africa. Both states seek control over ports in Somalia and its autonomous regions, in a bid for greater Red Sea influence, particularly along the strategic Bab-el-Mandeb strait.

China’s growing economic influence in this area threatens Abu Dhabi’s influence. Djibouti nationalised its Doraleh port, which had been under the UAE’s control, and later allowed Beijing a stake. Though this will not likely jeopardise their latest agreements, it is still a scenario that could test Chinese-Emirati relations.

We may be witnessing the start an era where the UAE is more regionally dominant

These latest agreements, meanwhile, could herald the start of strengthening ties between Abu Dhabi and Beijing, which could influence regional developments. And with the UAE increasingly using its diplomatic clout to win over other states - from Russia and China, to traditional allies such as the US and UK - we may be witnessing the start an era where the UAE is more regionally dominant.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].