Saudi oil attacks: Weaponising oil in the Gulf

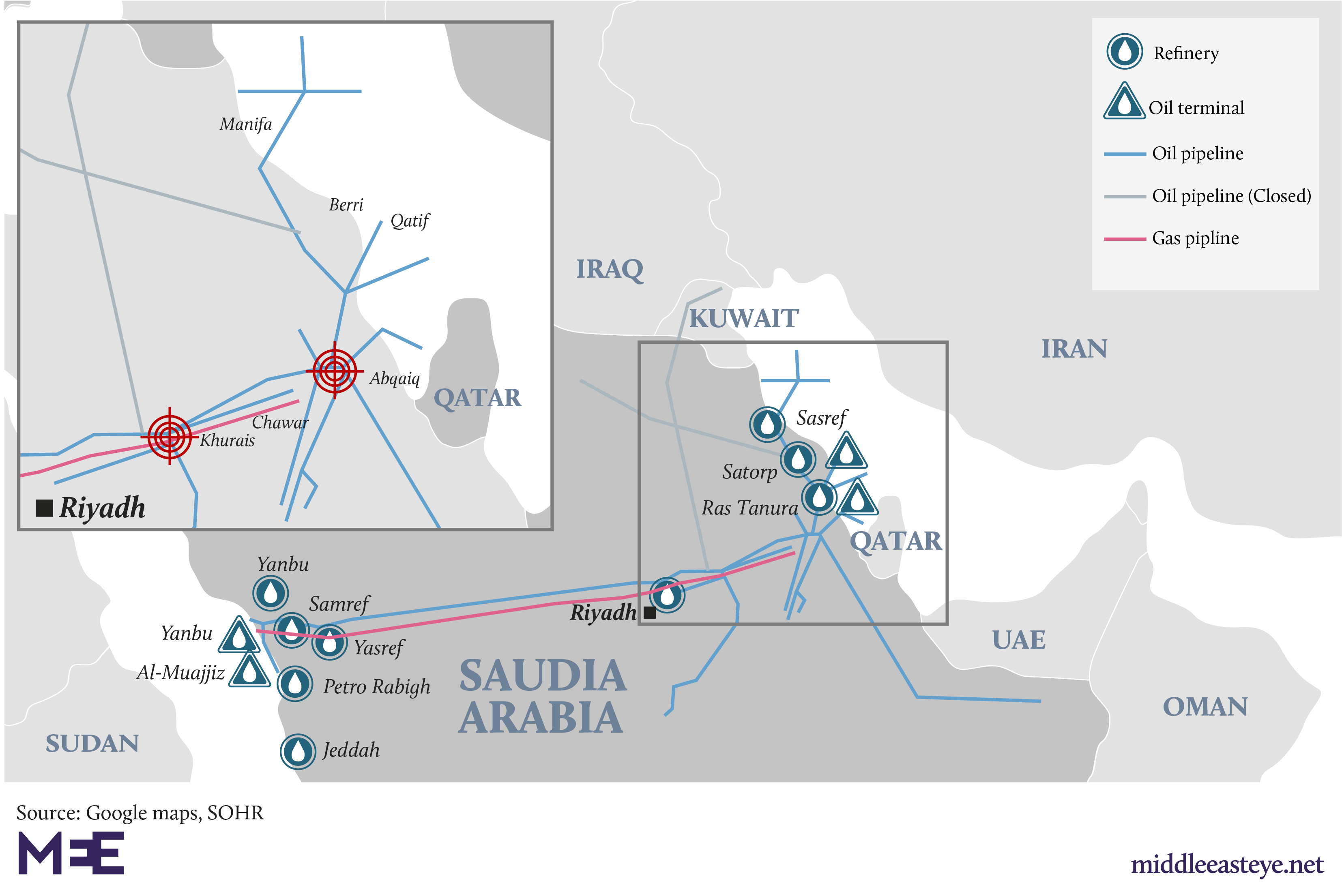

While the actor responsible for the air attacks on two Saudi Aramco facilities, Abqaiq and Khurais, is still being debated, with allegations ranging from Yemen’s Houthis to Iran, one fact is clear: the supply of Middle Eastern oil has been weaponised.

The Trump administration began this economic war by weaponising Iran’s oil through sanctions, depriving the Islamic Republic of its primary revenue.

Iran, whether or not it was responsible for the attacks, has benefitted nonetheless: the vulnerability of Saudi Arabia’s infrastructure and potential for disruption has been demonstrated, amplified through the global energy markets.

Regardless of the culprit, a Middle Eastern actor has used violence to attack an oil facility to further its political objectives. If the Houthis were responsible, a Yemeni non-state actor forced the world to focus on the unrelenting Saudi air campaign there.

If Iran was responsible, it sent a message to US President Donald Trump before an election year about how vulnerable the market is to fluctuations.

Determining culpability

The Abqaiq facility refines crude oil from fields such as Khurais and the mega-field Ghawar, among the largest in the world.

The latest attack was not the first time these facilities have been targeted. In 2006, al-Qaeda attempted a failed suicide attack on Abqaiq with explosive-laden vehicles. In 2012, the Khurais facility was attacked from cyberspace after a successful hack, allegedly by Iran.

Most recently, both facilities were targeted from the air, disrupting Saudi Arabia’s oil supply and its role as a swing producer, and raising the price per barrel.

There are four scenarios involving the culprit and origin of the attacks: that the Houthis acted on their own, that the Houthis acted on Iran’s orders, that Iran used Iraqi territory and allied Shia militias to attack, or that the attack originated from Iranian territory.

The fact that there are four scenarios indicates how amorphous Middle Eastern conflicts have become today.

Iran can leverage a number of non-state actors in a low-intensity conflict with Saudi Arabia and the US

On 16 October 1987, a Chinese-made Silkworm missile hit a Kuwaiti oil tanker under US protection. There was little doubt that Iran had launched the missile, and the US did not hesitate to retaliate.

In 1987, the conflict involved four nation states: Iran attacked Kuwait because it was supporting Iraq financially during the 1980-88 Iran-Iraq war. The US sided with Kuwait and Iraq.

The Houthis certainly have a motive for the latest attacks. In terms of technological capabilities, this past May, the Houthis claimed responsibility for a drone attack on a Saudi Arabian oil pipeline west of Riyadh, demonstrating a significant development in their military capabilities. The drone flew more than 800km into Saudi territory.

Iran can leverage a number of non-state actors in a low-intensity conflict with Saudi Arabia and the US.

For the sake of plausible deniability, Iran could use proxies such as Hezbollah to train the Houthis to launch sophisticated long-range attacks, or its Iraqi Shia militias. Using these non-state actors, one state, Iran, might have affected the global price of oil and the policies of the Organisation of the Petroleum Exporting Countries.

The price of oil

Saudi Arabia provides 10 percent of the world’s oil supplies, at 7.4 million barrels per day, and the latest attack halved its production. The attacks came as the national oil company, Saudi Aramco, was about to launch a public offering.

While the Trump administration has accused Iran of targeting not just Saudi Arabia, but the global oil supply, US oil firms stand to benefit from the rise of the price per barrel. Russia will also benefit, as its economy has suffered from low oil prices.

The price of oil rose by more than 10 percent, to $68, in the wake of the attacks. China stands to lose, as it imports most of its oil from the Gulf, and loses $1.1bn for each dollar the price per barrel increases.

Even while Saudi Arabia has taken a hit to its infrastructure, its remaining exports will still earn more as a result of the price increase.

At first glance, it might appear that both the US and Saudi Arabia have no incentive to defuse the situation, as they have much to gain financially. But while major US oil firms would reap windfall profits, if rising oil prices spur a recession, it will hurt Trump’s chances for re-election.

Mutually assured destruction

During the long-running Iranian-Saudi cold war, neither state attacked the other’s oil facilities for fear of mutual destruction of the infrastructure linked to their major export assets.

Yet, as US sanctions have substantially reduced Iran’s export capacity, Tehran is no longer deterred by that fear. If the US were to strike Iran, the Islamic Republic would have little to lose by unleashing an all-out strike on Saudi oil infrastructure.

Thus, regardless of the actor behind the recent air attacks, the vulnerability of Saudi Arabia’s oil infrastructure has been demonstrated to Riyadh and the world.

The “evidence” the Trump administration produces to implicate the culprit should be examined with a critical eye, given that these tensions began in May with the deployment of a massive military force towards the Gulf to threaten Iran. That deployment was based on a flimsy pretext, a response to unspecified threats allegedly posed by Iran to US forces in the region - what an Iranian official described as “fake intelligence”.

Nonetheless, what has been made manifest is how one actor in the Middle East can weaponise oil. While oil prices rose 10 percent as of Monday, a long-term disruption is unlikely - but what recent events have shown is the potential of an even greater strike on Saudi Arabia’s oil infrastructure, were the US foolhardy enough to escalate the conflict with Iran.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].