Politics and poetry: The female Muslim wordsmith making waves

The poet Suhaiymah Manzoor-Khan sits in the Students’ Union at the School of Oriental and African Studies in London, carrying a rucksack and wearing casual trousers and earrings that coordinate with her white hijab.

It's been a busy few weeks. Aside from celebrating her birthday (she’s just turned 25), she’s also promoting Postcolonial Banter, her debut volume of poetry.

The book is a wide-ranging work, contrasting exposes of state-led racism, the Prevent programme and the psychological trauma of surveillance with celebrations of Muslim identity as a cosmopolitan vision for life in Britain.

The book is a culmination of her growing profile: Manzoor-Khan has enjoyed increased popularity during the past few years, appealing to some who may not otherwise engage with poetry. Aside from millions of views on the Roundhouse Facebook page, she has performed on BBC Radio, Sky TV, ITV and at several TEDx events, among others.

However, she has never studied poetry. She graduated in history from Cambridge in 2016, followed by an MA at SOAS.

“My background is in history and post-colonial studies,” she says. “Poetry is like a secondary language for me with which I can disrupt the power that runs through narrative.”

Birth of a poet

Manzoor-Khan was born in Bradford in 1994 and grew up between the city and nearby Leeds. Her grandparents moved to Britain in 1962 from Punjab in Pakistan, settling in Yorkshire to work in the mill factories.

At school, Manzoor-Khan played the piano like many others. But she was especially attracted to the narratives of stories, including Roald Dahl's Matilda, The Lord Of The Ring films and songs by Adele and The Carpenters.

“I would listen to a song and ask myself what if the man or the woman said something else, or acted in a different way," she says. "Would the song change and the feeling of it?”

Manzoor-Khan came to poetry by chance at 20, during her BA studies at Cambridge. "I was just having a difficult time," she recalls, "and I went to see the college nurse, and she said: 'What's something you would like to do but you think you can't do?' Nothing to do with education, or academia, just something else.

"And I said: 'Oh, I think slam poetry is really cool, but I don't think I can do that'. So, then, [the nurse] signed me in for an open mic night, and yeah."

From there, Manzoor-Khan began writing and performing spoken-word poetry, a genre which crosses over heavily with slam poetry as well as the lyricism of rap. Performed rather than read, it is renown for its rhythms and vibes.

“I was writing these poems and asking myself, could this be poetry?" she says. "Because my writing is not linear but more emotive and my collection is formulated according to this style.”

While studying, Manzoor-Khan also co-wrote A FLY Girl’s Guide To University: Being A Woman of Colour At Cambridge And Other Institutions Of Elitism And Power.

How did she find life there?

"Cambridge is as it's expected to be," she says, "an elite, exclusive institution and it has a deep history of maintaining hierarchy and access to knowledge that are both race and gender-based. It's the place where colonial nations and even post-colonial nations educate their establishment; not necessarily teaching them to think critically but to reproduce a type of think, a type of debating that always maintains the status quo."

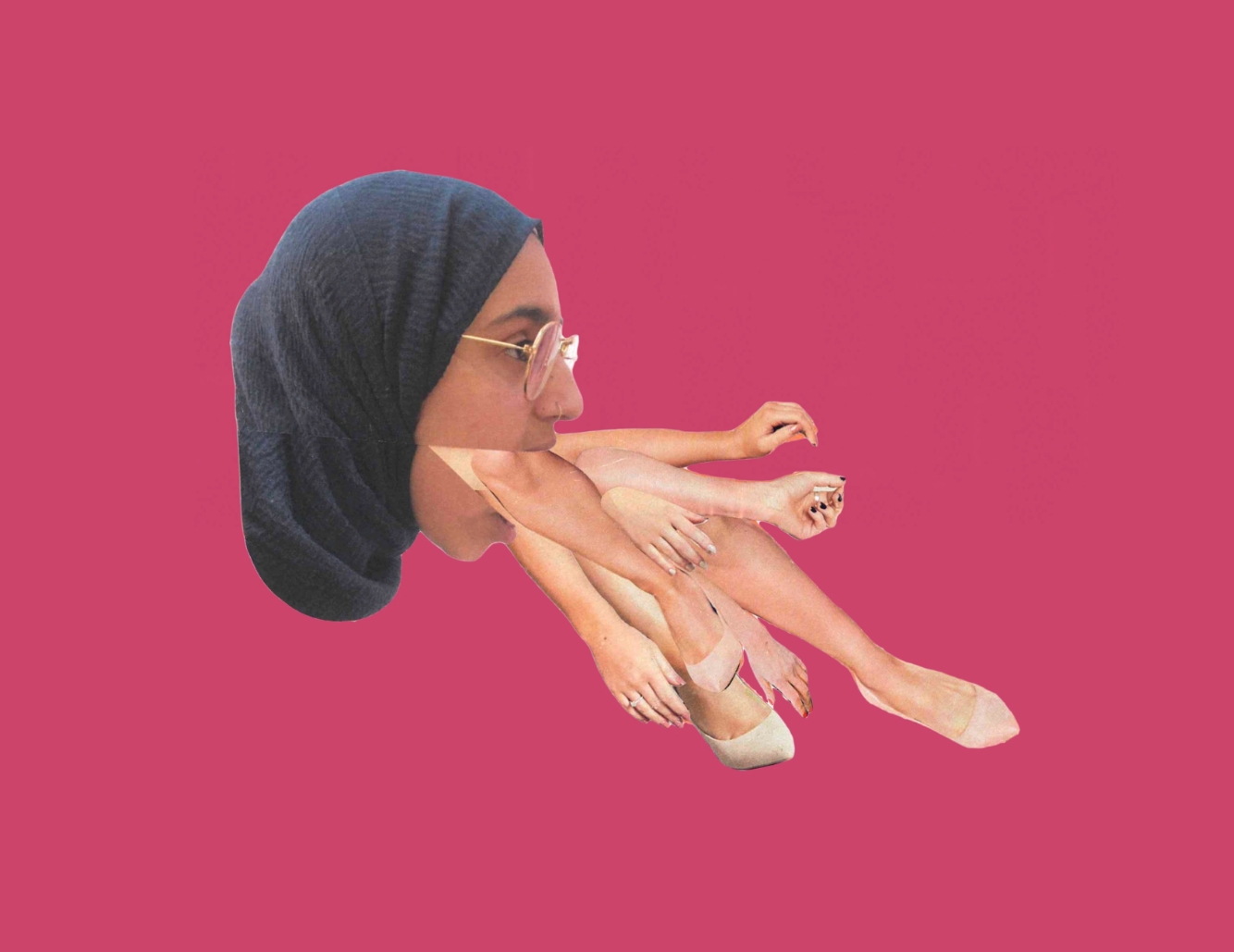

The cover of Postcolonial Banter (see main image) depicts a self-portrait collage that Manzoor-Khan made during her degree studies.

It depicts, she says, her finding her own voice and vomiting everything she had internalised of "colonial violence and white supremacy" as well as expelling violence based on gender, faith, race and class.

How to disrupt the narrative

Manzoor-Khan's work captivates audiences with its energetic and finely rhymed words that reflect on the political and social debate in the UK and within Asian and black communities.

Most of her poems in the Postcolonial Banter collection have been triggered by her performances, family history, listening to the news or recalling a past event.

"The knowledge of immigrants, from my family, I think it is an important type of knowledge. They did not give me books to read but just telling me stories of their histories; the stories that your grandmother or your mum tells you. It is a valued form of knowledge and it educated me of different values and experiences."

Her grandmother attended her London book launch, wearing a traditional Punjabi dress, but does not speak or read English. Instead, Manzoor-Khan translates the poetry for her. At the reading, she tells the audience that the language barrier "is a manifestation of the violence of the colonial language".

A week or two later, Manzoor-Khan reflects on how she creates a piece. “Of course audio comes first and there is a layer of anger that triggers the poem,” she says. “I would, for example, be listening to the radio and I would go and write a poem. My poem would be the response I wish someone else would give. I would say to myself: ‘Someone had to say something about this and disrupt the narrative'.”

This process can be seen in a work whose title was snatched from British news headlines: School Inspectors In England Have Been Told To Start Asking Young Girls In Primary School Why They Are Wearing A Hijab In Order To Ascertain If They Are Being Sexualised. It is dedicated to Ofsted, the UK’s controversial school inspection body.

And works such as Virtue Of Disobedience have an almost omnipresent sensibility:

We are the disobedient

look upon us and despair

for we outlast history, time, and memory

we are always there

We are the unquenchable thirst for justice

the bodies that do not bend

tongues you cannot straightjacket

and eyes that will not be turned blind

We are the step you trip on in the night

the nightmare you wake from but cannot recall

the lump under the rolling hill that reminds you what is buried there

We are the disobedient

We bear witness and we testify

We love despite the lie that we are not worthy

We hold despite being told we should hide

Yes - we are the disobedient

who refuse to die

for bodies without eulogies will never remain in their graves

we are the ghosts of the unmourned

and the spirits of the never-grieved

We are the original traitors to the tireless tyrant

Life as a British Muslim

Manzoor-Khan is the third generation of her family to live in the UK. The majority of her life has been lived in the aftermath of the 9/11 and 7/7 attacks, the fallout from which has shaped the narrative of Muslim life in the UK – but also left many British Muslim intellectuals wary of speaking out on issues of identity.

'I keep always asking when diaspora ends? I mean, when do you stop being from somewhere else?'

Suhaiymah Manzoor-Khan, poet

But after years of a negative portrayal of Muslims in British media and politics, poets like Manzoor-Khan are shaping a new lexicon of metaphors, images and emotions to reclaim their sense of belonging.

“I keep always asking when diaspora ends?” she says in reference to her family ancestry. “I mean, when do you stop being from somewhere else?"

I’ve visited Pakistan once in my life and just for three months in 2017 to learn the language and there is nothing else there for me. I am from here.”

She uses these emotions in British Values, which dissects the language of politics and mainstream media, creating a more intimate identity that stems from her life as a British Muslim:

Britain is bismillah

Britain is basmati rice

Britain is box braids and black barbers’ shops, Bollywood and bhangra

Britain is Bradford and Barking and Birmingham

Britain is biriyani and black beans

Britain is black, Britain is brown

Britain is boys blasting dubstep on the bus to town

Britain is body-popping outside the tube

Britain is Brick Lane before it was cool

Britain is bilingual

Britain is the burka

Britain is praying in the changing rooms

Britain has its feet in your sink

Britain is bad at knowing itself, belligerent, and boring

Britain has not Changed Beyond Recognition

recognise it was never one thing

'Poetry is a win-win for me'

Manzoor-Khan's profile is now growing. Her fame is such that the Metropolitan Police, which covers London, invited her last year to perform during Eid. Feeling uncomfortable, Manzoor-Khan declined, which is unsurprising given how much of her work examines state surveillance and police relations.

She also withdrew from the Bradford Literature Festival after its links to the government's counter-extremism strategy were revealed.

Instead, she is content to let her words talk to her audiences, using feelings and emotions “as a form of knowledge”.

“I had access to two different worlds during my studies," she explains. "My family and academic life. But if a border guard stops my family, I can't explain to them in academic terms how the state discriminates against them. Who cares what Michel Foucault said? But through poetry, I can translate theory, feelings and emotions that are relevant to people's lives.”

Her MA dissertation was entitled, “How the state constructs the Muslim subject in Britain?” which she turned into a work called This Is Not A Humanising Poem that has been heard by thousands, if not millions. In contrast, her dissertation was read by a handful of teachers.

“Poetry is a win-win for me,” she says.

Postcolonial Banter by Suhaiymah Manzoor-Khan is published by Verve Poetry Press.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].