From the Arab Spring to Brexit: Street artist makes the world her canvas

We are stood in a darkened room inside the Aga Khan Centre gallery at London’s King’s Cross. In a white summer top, black harem trousers and white sneakers, Bahia Shehab is flitting between members of the press - smiling, radiant and enthusiastic, despite the long flight from Cairo.

The Lebanese-Egyptian’s first solo exhibition in London - titled “At the corner of a dream", and inspired by the work of Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish - consists of a series of uncompromising films drawing out the universal human themes from the Arab experience since the uprisings of 2011. They are based on the murals the artist has painted in five international locations: Cairo, Beirut, Cephalonia, New York and Marrakech.

After the Muslim Brotherhood presidency of Mohamed Morsi was overthrown in 2013, and the current president Abdel Fattah el-Sisi took power, Shehab says there were strong threats against anyone who went down into the streets.

This motivated her to take her wall art outside Cairo. “I decided if I can’t paint in the city where I live, then every city in the world would be my canvas.” Vancouver became her first experiment, where she painted her first mural, “At the Corner of a Dream”, which subsequently became the title of her book and exhibition.

For Shehab, the poetry of Darwish is not only an inspiration but a great experiment in Arab modernity. “He dealt with all the issues we are struggling with today, and he managed to put our feelings and emotions into beautiful words.”

Shehab said Darwish summarised the struggle for all humanity, not just for the Arab world. “The language is Arabic but when you closely examine what he is saying it applies to all of us.”

‘Those Who Have No Land, Have No Sea’

The screens light up. Amid a backdrop of a gentle sea breeze and the sound of peaceful waves, a dead body floats in a swimming pool alongside several abandoned life jackets, observed, without empathy, by holiday sunloungers. Haunting and poignant, these pictures highlight our everyday indifferences to the mass suffering of humanity.

Her choice of location for Those Who Have No Land, Have No Sea was strategic - a swimming club on the Greek island of Cephalonia. “This is also where Greek Olympians train, and then represent their country at the world championship,” she says.

The Greek islands have been host to thousands of Syrian and other refugees making the dangerous crossing from Turkey as they sought safety in Europe.

Even before the war in Syria, Shehab viewed the vast migration of Africans to Europe as a post-colonial condition. “If the West hadn’t colonised these countries, and then portrayed themselves as prosperous, and instead helped create healthy governments thrive in their parts of the world, people would not want to flee these wars to kill themselves and their children in the sea.”

Nearly a decade after the start of the Arab revolt, EU countries continue to bicker about the intake of refugees. This week, four EU countries - Germany, France, Italy and Malta - have come together to break the deadlock over the refugee distribution mechanism. The meeting is significant, as Italy’s new government distances itself from the hard-line policies of former deputy prime minister Matteo Salvini.

“I think this is a sad condition because we have the technology. We know they are dying every day in the sea. Still governments decide to look the other way.”

Little has changed four years after Alan Kurdi’s small and lifeless body washed up on a Turkish beach. Recently, a Yemeni athlete, Hilal Ali Mohammed al-Hajj, drowned in the Atlantic while trying to reach Spain from Morocco.

Filippo Grandi, UN High Commissioner for Refugees, estimated that six lives were lost on average every day last year.

Placing culpability for the migrant crisis on the governments of the West, Shehab says: “Whatever is happening is a consequence of their action, it is a vicious cycle.”

A rapturous thunderclap followed by a background music change signals the start of the next film.

In We Love Life (2019), Shehab reflects on Darwish’s verse that reads “We love life, if we had access to it.”

The film, shot in Morocco, stages a classic white wedding in the ruins of a conflict zone. An autorickshaw is driving the couple in moving traffic, concrete buildings are reduced to rubble except for a grubby butcher’s shop with festive lights. Local pop music is blaring in the background.

The bullet-riddled buildings and dilapidated cities embody the disenfranchised Arab youth, denied an education, jobs and a future. The wedding represents the carefree life they’ve been denied.

‘No, and a thousand times No’

Shehab’s wall art captured global attention after the start of the Arab Spring in December 2010 in Tunisia. At first, she felt invisible and unheard. But she found a means of resistance in her paintbrush, stencils and colours.

She painted the lam-alif’ script, meaning “No” in Arabic, to resist military rule, violence, fascism and sectarian division.

She used “No” in a thousand different ways, which she derived after researching 1,400 years of historic Islamic scriptures she found on buildings, mosques, plates, textiles, pottery and books from countries as far apart as Spain, China, Afghanistan and Iran, where Islam had thrived at one point in history or another.

A recreation of her beliefs and sentiments can be seen in "Erasing Memory", installed against a black and white brick wall. Her calligraffiti is expunged in subsequent scenes with accompanying sounds of street protesters’ chants.

As an artist, historian, activist and designer, Shehab is no stranger to wearing different hats. But what really drives her is humanity and empathy. Empathy for injustices, empathy for the imprisoned women, empathy for refugees.

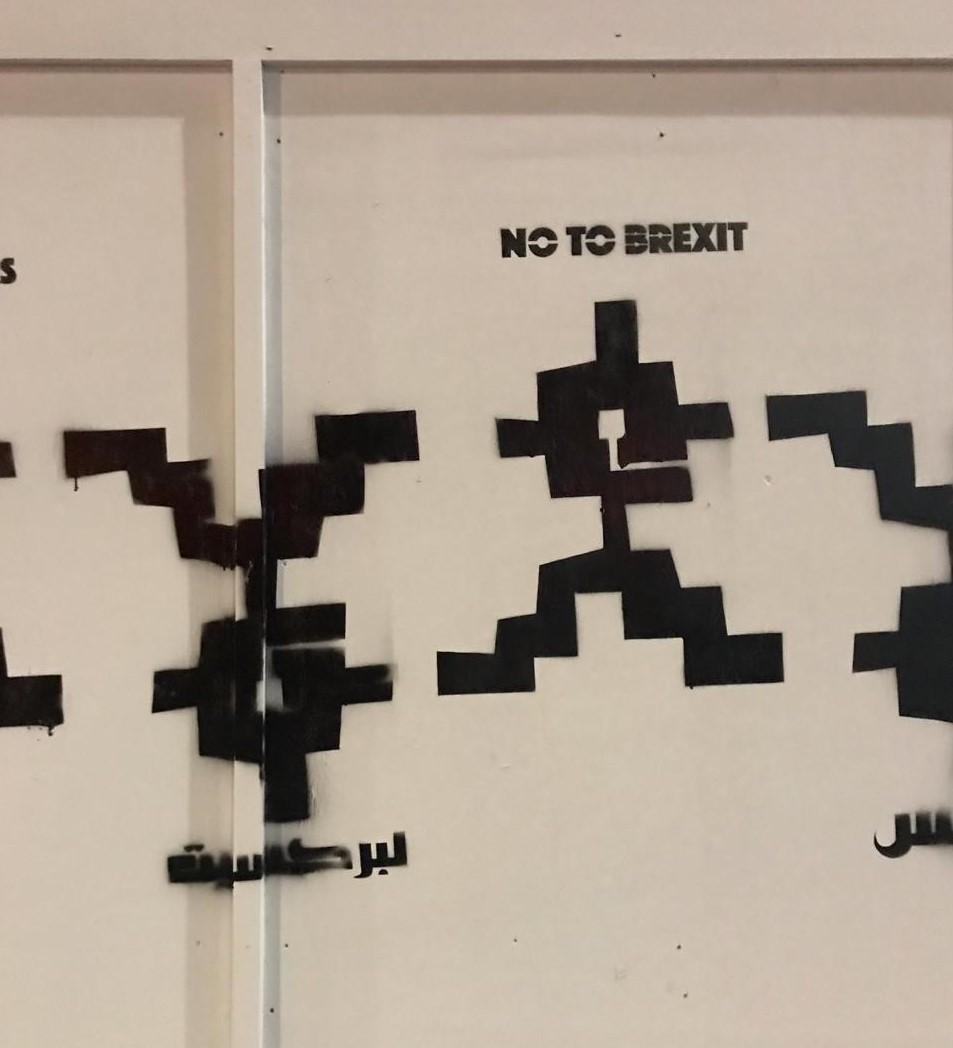

This is evident in one of her recent murals on Clerkenwell Road in London, which speaks to the UK’s own political crisis. "The reason why I got involved with Brexit is because I wanted to paint 'No To Borders' and 'No To Brexit'."

Shehab believes Brexit is not something that only concerns people living in the UK. "It is much bigger. It is part of a union that was created decades ago and the world looked at it with admiration. Now that concept is breaking up, and it is a big disappointment.

"What we are missing here is the word union. The concept of a union - the United States, United Kingdom. This is what has been advancing humanity," she adds.

Whether it is politics at home or internationally, reviving Islamic art and scriptures, or resisting Islamophobia, Shehab is passionate about why more women should be heard.

She grew up during the civil war in Beirut. Since her early twenties, as a young working woman, following 9/11 and the war in Iraq, she has been subject to harsh and unwarranted criticism about Muslim women.

"I witnessed how the war in Iraq unfolded. There is always a misconception about who we are, what is our identity and what do we stand for."

Through her work, Shehab is determined that people should rethink what they are being told. She does this by conveying a different perspective on the identity of an Arab woman. "Mostly we are portrayed as weak, submissive, who need to be liberated."

Since 2015, Shehab has painted in 15 cities around the world and in 2016 featured on the BBC's 100 Women list.

The following year, in 2017, she became the first Arab woman to receive the Unesco-Sharjah Prize for Arab Culture for integrating historical Arabic calligraphic scripts in her street art to draw attention to modern political conflicts.

In the same year, Shehab became a laureate of the Prince Claus Award from the Netherlands.

She draws inspiration from the unknown masters of Islamic art. Unknown because there are no biographies or big books written about them. "But their work has lived on, and I have been studying it for years now," she says.

Shehab feels at home in the streets, in dark alleys, amid the homeless, the drug addicts and the marginalised.

"I believe art belongs on the street, people need art. It is a beautiful way to create conversation around difficult topics." She believes that regardless of education, income or background, art brings people and ideas together.

The same streets can be haunting, isolating, dark and, at times, ephemeral. This does not deter Shehab, who feels messages that were once obscured can be shared with the world. "With cameras and social media it is a completely different dynamic now. If people see it on the street it’s amazing. If not, there is the digital, visual street.

"We live in an interesting time, especially in terms of how history will be written and the conversations we have from now on."

The exhibition of Bahia Shehab's “At the corner of a dream" continues at the Aga Khan Centre gallery, London, till January 2020

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].