The Lebanese people are reclaiming their future. Can they seize it?

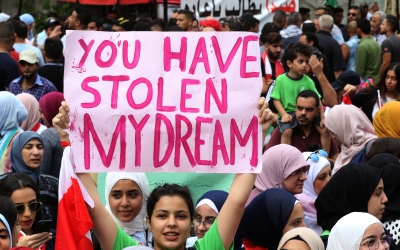

It has been almost two weeks since the start of a spontaneous, countrywide rebellion in Lebanon against a spreading economic crisis and government austerity measures.

It is unclear how the revolt will end, now that the Lebanese Prime Minister Saad Hariri has resigned, but the long-resilient sectarian political system in Lebanon has been shaken to its foundations.

The revolt has seen major achievements due to how it has been organised. The geographically decentralised protests have been independent of major political parties and united across sectarian lines, and they have used non-violent civil disobedience, while rejecting any activist “superstars” coopting the movement.

Demanding social justice

The protests represent a textbook “grassroots revolt” - spontaneous, broad-based and non-hierarchical, with ordinary people making demands for social justice. Despite the challenges that will face the political movement born from this revolt, many are hopeful that it will yield positive change in the long run.

The protests today are the result of an incompetent and corrupt sectarian patronage system built during the post-war period

The movement is not organisationally mature enough to immediately overthrow the entire confessional system. The main political parties are too well-entrenched, and they seem poised to wait the movement out. When it comes to proposals for the next steps, little consensus has emerged from the protests, beyond the rallying cries of “Revolution” and “The people want the fall of the regime”.

A constitutional process to install a transitional government that would implement immediate reforms - and set a course for more radical structural changes - does exist, however, and may be the best way to uproot the country’s deeply entrenched political system.

The seeds of the current political and economic crisis were planted at the end of Lebanon’s 15-year civil war, which ended in 1990 and was followed by three decades of rule by mostly the same civil war bosses. Exchanging their military fatigues for suits and ties, these bosses remodelled themselves as statesmen and parliamentarians.

Neoliberalism and cronyism

The neoliberal era that followed the civil war, led by the late Rafik Hariri, centred on rebuilding Lebanon to attract foreign investment and businesses. But rebuilding war-torn infrastructure, transportation systems, hospitals and schools were not the priorities.

The post-civil war reconstruction economy rehabilitated the warlords of the sectarian system. Syrian control in Lebanon after the war helped build a vassal state run by corrupt and compliant Lebanese politicians who siphoned funds for themselves and the regime in Damascus.

The marriage of Hariri’s neoliberal reconstruction project with Syrian political control developed a sophisticated sectarian patronage system. Corruption was “legalised” through crony contracts, kickbacks, payoffs and ghost ministries with huge budgets used to extract state funds.

In the early 1990s, Lebanese political bosses either coopted or gutted institutions such as unions, professional associations and opposition parties. Public schools and hospitals were defunded.

The vast majority of even working-class Lebanese today do not send their kids to public schools, while public hospitals are only used by those who have no other choice.

The protests today are the result of an incompetent and corrupt sectarian patronage system built during the post-war period, which managed to rack up more than $80bn in debt - yet cannot deliver basic electricity to all of its citizens.

Cross-sectarian revolt

After 30 years of crony capitalism, astronomical inequality, rampant corruption and incompetence, poor state services, and a growing debt crisis that threatens to bankrupt the country, the Lebanese people have finally had enough.

The cross-sectarian solidarity of the revolt, which covered the country from north to south, has stunned the political class. The disaffected youth, the unemployed, underemployed, students, and others marginalised by the current economic system were the first to take to the streets, but the revolt now encompasses all economic classes.

Civil society groups and “professional” activists were latecomers. During the first week of protests, it was clear that the citizens of Lebanon did not want anyone to speak for them - not even civil society leaders, and certainly no one connected to political parties.

The voice of the citizens reigned supreme, broadcast on many TV stations. Wherever they occupied public spaces - in Beirut, Tripoli, Sidon or other cities and towns - people spoke for themselves.

Proposals and concessions presented by Lebanese Prime Minister Saad Hariri were immediately rejected by the people, showing they no longer had any confidence that the political class could provide solutions.

Hariri’s proposals included no new taxes, a 50 percent reduction in the salaries of senior government officials, taxing banks, and other cosmetic concessions. All of this was too little, too late, and did not come close to the longer-term structural demands of the protesters.

Out of touch

The eventual response from President Michel Aoun, coming more than a week after protests began, was also rejected by the people. His response showed how out of touch the president was with the seriousness of the situation.

Acknowledging the demands of the protesters and asking for more time for reforms was not good enough. Still worse, Aoun had no immediate, concrete proposals, and asked the grassroots, leaderless movement to choose representatives to negotiate with him directly.

Nasrallah also hinted at nefarious financial and political interference by opportunists, should protests persist

The response from Hezbollah Secretary-General Hassan Nasrallah, a day after Aoun’s, was in some ways no different - but it had a bigger effect on the revolt’s momentum. He told protesters that they had achieved what they could, and that they should accept Hariri’s concessions and go home.

He also hinted at nefarious financial and political interference by opportunists, should demonstrations persist. Nasrallah’s speech was a blow to the cross-sectarian solidarity that had flourished in the revolt. Many working-class Shia that support the party had also been part of the rebellion from its inception.

The responses of both Aoun and Nasrallah also opened the door to counter-protests by their supporters. Despite these admonishments, people were not deterred, and have continued to protest in squares and streets across the country, albeit in smaller numbers in some areas.

Constitutional roadmap

Lebanon’s internal politics are complex. The geopolitics of the region are also unsettled, especially given challenges and failures in consolidating other recent revolutions in the Arab world. As such, the Lebanese people will have to tread carefully moving forward, while not missing a historic opportunity to remake their political system.

Constitutional steps to begin resolving the crisis have been suggested by some activists, including the immediate resignation of Hariri. There have been discussions on a new transitional government that reflects the movement’s demands; the drafting of new laws to hold corrupt government officials accountable, and to amend the electoral system; and the holding of new parliamentary elections.

The overthrow of the current system is ambitious and fraught with challenges, including reactionary forces in the current ruling class who seek to remain in power.

It is unclear what will happen next. Protesters still hold the streets, persisting with road blocks and the occupation of public spaces. But what is certain is that a new political culture has been born through this revolt.

Lebanon’s people have come together in struggle - marching, chanting, discussing, and demanding change. Surprising even themselves, the people have gained renewed confidence that collectively they can take back their future.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].