Fight the system: Lebanese at protests teach children things can change

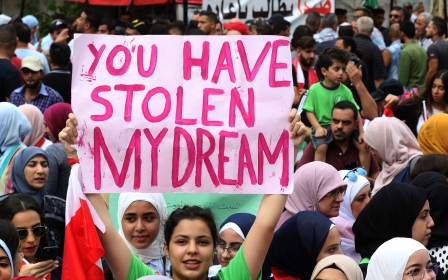

For hundreds of thousands of Lebanese, the protest movement has been an opportunity: to have their voices heard, to demand change and to prove solidarity.

But for the many parents at the demonstrations like Mohammed Hussein, they've also been an opportunity to teach their children that life in Lebanon can and should change.

Hussein has been taking his five children, dressed all in fatigues and carrying Lebanese flags, to the protests almost every day since they erupted on 17 October.

The 38-year-old painter comes from a working-class background and is illiterate, which only foments his desire for change.

“I want better things for my children, I want them to read and write, and to learn about what is really important in this life,” he told Middle East Eye in central Beirut's Riad al-Solh Square.

A series of longtime grievances - including corruption, high unemployment, lack of services and a national debt of $86bn - and recent proposed tax increases have pushed hundreds of thousands of Lebanese to protest across the country.

They have demanded reforms and an uprooting of the entire political class, which is accused of using Lebanon's fractured confessional political system of dividing the Lebanese.

The tiny Mediterranean country has a reputation of having a society divided along sectarian faultlines, though as the protests have shown, all Lebanese are united in suffering under the same leadership.

'I want better things for my children, I want them to read and write, and to learn about what is really important in this life'

- Mohammed Hussein, 38

It's a message that Hussein wants to get through to his children.

“I tell them about the different sects at the protests. I’m a Sunni from Beirut and a supporter of the Future Movement, but I tell them there are Shia protesting with us for the same things,” Hussein says.

According to Hussein, the first time he took his children to the protests, his nine-year-old daughter was afraid that Shia protesters might attack them.

“They learn this type of thinking from the language on the streets and from media, so I made sure to say hello to a Shia friend, and he told her that we are all here because we want to live and be happy,” Hussein said.

A civil war generation

Mazen Barazi, 43, like other parents Middle East Eye spoke to, comes from a generation born during the Lebanese 1975-90 civil war, and grew up with the remnants of a sectarian conflict that still haunts the country’s society.

“My children feel that Lebanon is their country once a year, during Independence Day,” said Barazi, who has been taking his seven-year-old and six-year-old boys to the protests whenever he can.

“For decades, people have been more attached to their political parties than their country, and I want my children to feel patriotic.”

Over the two weeks of protests, the largest in years, protesters have made pains to appear united against the political cadre that has been governing on a sectarian-based power-sharing system since the war ended.

“Whether we like it or not, our generation has inherited their parents’ political leanings, but our children’s generation is different,” Rania Garro said as she was leaving the protests in Downtown Beirut, where hours earlier she was offering free home-made food to protesters.

“We saw that we can be unified as a people, and we want our children to have that sense of patriotism.”

Garro’s friend, Carine Assaa, a lawyer, said her nine-year-old daughter has been going with her to the protests every day.

“They should know what’s happening. They need to know that there are people in power who are stealing from us,” Assaa said.

Assaa recounted how she used to cut school to go to rallies in support of Michel Aoun, the general who fled Lebanon at the end of the war and returned in 2005 to lead the Free Patriotic Movement and become president in 2016.

But, she said, the 84-year-old's political choices and the constant deterioration of the economy has led her to the streets.

'They need to know that there are people in power who are stealing from us'

- Carine Assaa, lawyer

“During our school days, we had the West Beirut and East Beirut mentality,” she said, in reference to frontline that divided the capital between Muslims and Christians during the civil war.

“We were separated from Muslims. But today my daughter goes to a mixed school where kids date and befriend from other sects. They don’t have that mentality and they don’t care for it.”

Assaa and Garro said that it is more important for them to teach their children that they cannot bring about change without some form of struggle against the system, and the current fight is against corruption and for their own future.

“Our parents lived the civil war and we lived it - and its aftermath - with them by default, without really understanding what was going on,” Barazi said.

It was therefore essential for him and his wife to explain the current crisis to their children, in the hope that they will always be aware that they deserve more than what the current government is giving the people.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].